By any comparison, Victorian hay-day of sail or today’s modern giants of the seas, the sailing barque, Bay of Bengal, three-masted, 260 feet long, built of ‘Government standard, best, best best iron’, to beyond Lloyd’s highest specification, was a large ship.

Launched from the Fairfield Yard at Govan on the Clyde by the respected shipbuilder, Henry Elder & Co., the 1695 ton ship slid down the ways in August 1875 to the cheers of a large crowd. Although it was still the period called the Golden Age of Sail, it was also a milestone in time which marked the zenith and the beginning of the end in the downward spiral of the great age of sailing

ships.

The barque Bay of Bengal. Courtesy of Peoples Collections.Wales.

It can be even more surprising now, to look back to that time, when it was clear that the progress of steam would revolutionise travel. And one might wonder why it was, that so many sailing vessels were still being built.

Iron, steam, screw and reliability, were providing competition that would obviously supersede timber and canvas. The truth at this time though, did not lie with any romantic attachment with the sailing era. A sailing ship could be built and operated for much less than a steamer. Moreover, sail, those magnificent ‘Greyhounds of the Sea’ were still faster – on a good day. And on the other hand, steamer’s that could carry over 2000 tons of cargo, were considerably more expensive to build and run. Instead, ship owners coldly calculated the comparative costs and remaining time before steam would make sailing ships obsolescent. Similar strategies that are being decided today with diesel and electric motor vehicles.

It was an inevitable reality for those who owned and ran sailing ships that they would crossover, or lose out to the steamship. Coincidentally, the number of cases involving criminal neglect of vessels and the fraudulent sinking or abandoning of sailing ships, increased. Inevitably, sailors before the mast began to either retire from the sea or moved to steamships. Ultimately, the ability and number of sailors who could manage such dangerous voyages in large sailing ships began to dwindle.

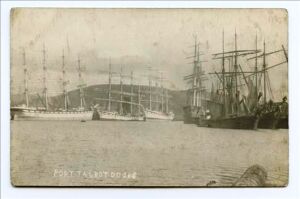

The Garthsnaid ‘Rouning the Horn’. Courtesy of Queensland State Library.

The Bay of Bengal, one of three sailing giants with, Bay of Naples and Bay of Biscay, were known to make up the Bay Line. Owners James J. Bullock & Co., London, very successfully ran the ships and large bulk cargoes across all the oceans of the world. After the Bay of Bengal was launched, she set a number of record voyage times and made lots of money Rounding the Horn and the Cape of Storms for her owners. The reminiscences of these epic voyages, accomplished by men of a marine grit not seen since, have become legend.

Still classed A1 by Lloyds, the Bay of Bengal was sold to the T. Beynon Shipping Co., of Cardiff for £6000 in 1901. As steamships and steam trains had attained almost complete mastery of commercial travel on land and sea, lots more coal was required everywhere. Nations required the ‘black gold’ fuel for their own development, and the coastal bunkering stations established around the world in order to keep steamers supplied with fuel.

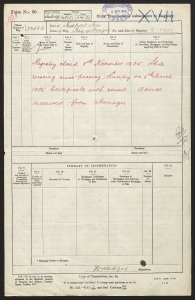

Advert for the sale of Bay of Bengal in 1901.

The Bay Line had been shipping long-haul world-wide, and the Bay of Bengal had become a frequent visitor to the east and west coast of South America. In February 1905, the iron barque was packed with good Welsh coal and set sail with her twenty–five crew from Port Talbot in Wales, on or before February 3. Her destination had been Taltal, on the west coast of Chile, but got no further than a few miles, when she was rammed by an ‘unknown’ steamer, off Lundy Island, in the George’s Channel.

Sailing ships berthed in Port Talbot at the turn of 19th,20th century. Courtesy of Peoples Collection.Wales.

With some serious damage, the Bay of Bengal became leaky at once, and she put back in to Cardiff for repairs. For whatever reason, the six following crewmen, all Irish, got cold feet and left the ship, and were replaced before the ship set off again.

Mahon, Patrick of Arklow. Seaman.

McCarthy, J. Age 24, of Cork.

Dublin, John. Age 49, of Dublin.

Curran, Michael. Age 45, of Wexford.

Burns, Michael. Age 32, of 15 Brook, Arklow.

Titson, Samuel. Age 28, of Kircabbin, County Down.

After repairs to the barque were completed, on or before March 4, the Bay of Bengal set sail for Taltal again, and ran into bad weather immediately.

After a period of bright sunshine, ten days of stormy weather began on the evening of the 4th. The barometer plummeted and Wales was stricken with strong gales that veered from west into the north, and caused extensive damage. The weather turned sunny again on the 11th, but cold and still windy, and the fear was that the weather would come easterly with snow.

Reports of ships in distress, and going down, soon began to filter in to ports. On the night of the 13th a storm with violent winds ‘not seen before’, struck the George’s Channel and Bay of Biscay. By the 15th the storm was cyclonic, creating whirlwinds of ‘extra ordinary fury’ and sinking large ships along the south coast of England and Ireland. The snow did not materialise but the rain was so heavy, it was impossible to walk through it, and the wind battered the whole southeast and east coast of Ireland. Extensive damage was recorded in both countries, which supposedly compared to the ‘Night of the Big Wind’ two years earlier, in 1903. The wind had swung right around to the SSE and then back again to the WNW, as the storm abated. It was a bad storm by any stretch of the imagination, and the Bay of Bengal had sailed into the abyss.

Amongst numerous reports of wreck and damage, April 21, produced a press article with the ominous title; ‘Signs of a Wreck off the Wicklow coast’. The reports continued and elaborated over a number of days, while all kinds of shipwreck material was being washed up along the east coast of Ireland. Animals, pieces of ships rails and furniture and in particular, an oar and lifebuoy with ‘Bay of Bengal’ carved on. There were no reports of any bodies. A small boat was recovered on the shore at Courtown, county Wexford.

Quite justifiably, it was believed possible, and even likely, given the ship’s excellent record, that the Bay of Bengal was still afloat and continuing her voyage. However, a sniff of profit was in the air, and the price for re insuring rose steeply. The telegraph had still not announced, and could not, the arrival of the Bay of Bengal at TalTal, and so, the betting proceeded at pace.

The seemingly distasteful practise of betting on the fate of a ship at sea, chalked up the Bay of Bengal on the board of The Overdue Market at Lloyds. They quoted a price of 35 guineas in the 100 for re insuring the ship against its loss. Notwithstanding, and according to her owners, the ship was not due at Taltal until ‘the middle of June’. A sport of merchants perhaps, the practise had been in operation for centuries, and it too was reaching a point of obsolescence as a result of improving communications. The telegraph cable had already snaked across the oceans’ floors and was delivering news instantly.

The odds reduced and the price rose through April and May, 45gns, 60gns, until the first message in a bottle from the stricken ship was found on the coast of Wexford. The news forced the odds against the survival for the ship and her crew skywards, and rose even further, week by week.

The first ‘Message in a Bottle’ – ‘A Sad Tale from The Sea’

The bottle was located on the shore at Donaghmore near Cahore, county Wexford by Mrs Brigid Ryan of Ballinagam. What was written on the paper that had been sealed in the bottle was reported in the article, ‘Sad Tale From The Sea’, published in the New Ross Herald on May 26.

“Lost on the 6th of March below Cahore. We observed a wall and ruined church opposite where we wrecked. Twenty five hands on board. The name of ship, Bay of Bengal. Related by captain going down. We belong to England.”

As the ship was still not due in Chilli until June, the owners believed and stated that the message was a hoax. This did nothing to deter the rise in the cost of betting on the ship’s fate from its skyward trajectory. After this story broke, the price of re insuring the ship rose to its ‘maximum’ of 90 guineas in the 100. The profit from a successful re insurance claim due to being overdue and lost, had reduced to 10%. Handsome nevertheless, if one could afford the punt.

The wording in the message does present some questions but we have two more bottles and messages to go.

The second Message In A Bottle – ‘Message From The Sea’

The Bay of Bengal was posted ‘missing’ after the second week in June. The Eastern Daily Press reported in ‘Relic From A Missing Ship’ on June 20, that a fishing boat from Yarmouth fishing in the Westward grounds picked up a ‘substantial’ bucket with the Bay of Bengal painted on it. It was retrieved 20 miles from the Scilly Isles.

The Daily Telegraph reported in the article, ‘Message From The Sea’, printed on July 1, that two young boys had found a sealed bottle on the sands at Swansea. In the bottle there was a piece of paper on which the following message was written.

“The Bay of Bengal, ship, is sinking, in the Bristol Channel, signed, W.C. Remember my mother who is in Scotland. Farewell forever.”

The only ‘W.C.’ possibly being part of the crew, was W. McCaw, boatswain, who was reported to have been living in Cardiff.

By August, there was still no trace of the barque or her crew, and the ship was unofficially declared lost and ‘uninsurable’, and reported to have been withdrawn from the Overdue List.

A full list of the crew, in so far as they were known, was published. Insurers’ terminology, shipping practises or legal jargon, it is amazing that the ship had still not yet been officially declared, missing believed lost, in August.

The third Message In A Bottle – ‘Ominous Find By Lowestoft Man’

James Gorble of Lowestoft discovered a curious bottle floating in the sea while working at Felixstowe. The Norwich Mercury reported in ‘Ominous Find by Lowestoft Man’ on September 9, that it seemed to have been a long time in the sea. A note was retrieved from the sealed bottle and on it the following was written.

“Ship Bay of Bengal, Biscay, June 21, 1902:- To whoever should find this message say we are foundering. Send this please to Miss Malcolm, 24 High Street, Whitstable, saying I am dead and there is no hope. God bless the man who sends it. – Frederick Malcolm.”

It wasn’t until reports on September 22 declared that Lloyd’s relented, and rang the Lutine Bell, officially declaring the Bay of Bengal missing, believed lost, that all bets were off.

Conclusion

The third bottle and message may have represented an affair of the heart and the messenger’s reporting of his own death might have been greatly exaggerated. 24 High Street, Whitstable, a considerable distance from the event, is an Indian restaurant now, and Malcolm, not an unfamiliar Whitstable name, details should have been easily confirmed. Sailors by their nature perhaps, and opportunity, went missing in all manner of ways. I am disregarding this report if only because the date is very wrong, there was more than one Bay of Bengal, and the distance the bottle was found from the scene, was great. It also appears that the messenger was a little shy of being sought out, dead or alive.

The second bottle was found in a place, Swansea, which was very much in keeping with events, and seems to have been genuine.

The first bottle, despite some ambiguity in the message, and along with numerous other pieces from the same ship found along the same coast, were later believed, ‘officially’, to have marked the general area where the large barque and its crew were lost. This is significant, as it suggests that the ship was probably lost on or before March 6, but this is by no means certain. It would also suggest that, the ship did not get very far down the Channel, before it was driven back during the earlier days of that stormy period. One cannot rule out though, that repairs after the earlier collision were insufficient, and that the ship began to leak again soon after its departure from Cardiff, and foundered.

So, where is the lost Bay of Bengal now? The clue may be in the reference to the ruined Church and the wall, which the author of the message could see as the ship was sinking. You may ask all kinds of question like: How? Seen with what? How far from the shore? Why some of the crew did not get into a boat or on to a raft, or swim etc.. Alas, these questions cannot be answered – yet.

INFOMAR a fantastic of body of scientists and oceanographers, an amalgam of the two bodies, Marine Institute and Geological Survey Office Ireland, have been mapping the seabed around Ireland, producing the most wonderful image record of the seabed and what lays on it.

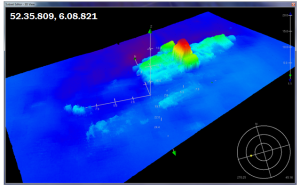

Image of Unidentified wreck off Donaghmore. Courtesy of INFOMAR

First detected in 2017 and confirmed in 2019, the large wreck shown in the image was discovered. It proved to be a previously ‘uncharted’ shipwreck. Also, and unusually, it does not appear on the fishermen’s ‘snag charts’ for the area in the author’s possession.

Cahore, Donaghmore & Roney Point – Wreck site. Images courtesy of Google and Dr Eugene O’Loughlin

The ‘unidentified’ wreck lies two miles off the shore opposite Donaghmore, where there is a substantial ruin of an ancient church surrounded by an equally old wall. There is a very old graveyard in the church grounds, and it is recorded, that unidentified shipwrecked sailors have been buried there. The attached image shows the headstone marking this place, Sailors’ Hole.

The ruin is still visible from where the ‘unidentified’ shipwreck lies, but maybe hard to see with the naked eye on a poor day. With any kind of a telescope it would have been clearly visible. Wreckage, old timbers, and corpses, have come ashore on this small secluded beach for years, but as there were so many wrecks along the coast, no one is sure of their origins.

It is intended to investigate the wreck during the coming months in an attempt to identify it, and maybe put this particular mystery of the ‘message in a bottle’ to bed. A result might also be a comfort to the descendants of the crew from the barque, Bay of Bengal.

Crew List

The number of crew on the Bay of Bengal was said to have been 25. Some confusion seems to have arisen after the six Irish sailors departed the ship when she returned to Cardiff. The total number of different names reported (As per printed reports.) in differing newspapers and listed here, amounts to 30 or 31. One possible duplicate.

Baker, Henry. Second mate (Of Cardiff). 30 Harebell Street Liverpool.

Briar(Bear), W. AB. Age 47. Adam Street (Sailor’s Home)*

Christennsen, H. Of Malmo. Age 34. (36) Georges Street. Sweden.

Deaking(Dealling), T. AB. Age 44(45). Of Cardiff. Cowes. (Sailor’s Home)

Dunbar, Charles. Age 54 (35). Of Weymouth NS. Margaret Street.

Evans, Evan Thomas Timothy. Apprentice. Age 16. Of New Quay.

Gerrard, James. Master. Derby Road, Huyton, Liverpool.

Grant, Earnest Augustus. Apprentice. Age 16. Of Newport.

Hansen, H. AB. Age 12 . South….

Harrington, H. Apprentice. (Possible duplicate of Harrison.)

Harrison, James Hadfield. Apprentice. Of Dunkenfield. Of Newport.

Janssen, Fredrik Carpenter. (Of London) 3 Loudoun Square, Cardiff.*

Jones, William. Age 33-35 (39). Of Carnarvon. Margaret Street.

MacCleod, A. Age 31,(36) Of Stornoway. Georges Street.

MacClymont, J. Age 19. OS. 21 Langdon Street, Swansea.

McCaw, W. Botswain. 8 Louise Street, Cardiff.

Nillson (Milsom), J.P. Sailmaker. Age 43. 18? Brute Road, Cardiff.

Nolan, W. Age 31 of Waterford.

Owens, J. Age 46. Of Holyhead.

Pearson, T. (S) Age 48. Of Cardiff. 18 Patrick Street. Liverpool.

Robertson, Lionel. Apprentice. Age 18. Of Clapham.

Ross(Rose), A. St. Steward. Age 42. 11 Travis Street, Barry. [A.St. Rose.]

Rowe, James. Cook. Age 30. 13 Maesteg Road, Bryn, Fort Talbot.

Rowlands, John. First Mate. (Of Havordsweet). 14 Cogan Terrace, Cardiff.

Savage, R.(S)O. OS. 56 Brunswick Street, Swansea.

Savage,G. OSR. Age 20. (Possible duplicate.)

Smith, John. Apprentice. Age 18. Of South Shields.

Stephens, J. AB. Age 44(47). Of London. Christe….34 Georges Street.

Thorsen, Thomas. Age 54. Of Stavanger.

Williams, J.B. Boatswain. Age 28. 40 Georges Street. Cardiff

Wormely (Woraley), R. AB. Age 37. 13 Evelyn Street.*

*Hadeed, Wornley, Beer [Hansen, Wormley (Woraley) and Bear(Briar), joined the ‘steamer’ when the six Irish crewmen departed following the ship’s return to Cardiff.

(Research is continuing on aspects of this article and this article will be updated. A search for this lost ship will take place in 2021.

The title image is of a bottle from a shipwreck in Dublin Bay, and has remained sealed with a roll of paper within. It remains the property of the author.)

Message In A Bottle, Continued

Divers log Sunday May 16, 2021.

Small boat dive off Cahore on ‘Unknown’ site recorded by INFOMAR. The wreck site is 2.5 miles off the coastline directly opposite the Old Church ruins and graveyard at Donaghmore.

The the dive took place on slack water, two hours before HW at Wicklow, which occurred at 1500 hrs.

The max depth was 19 metres and was nothing short of a 20 minute shitty dive. The visibility could not have been more that 12 inches with an upsetting undertow. The terrible visibility seemingly caused by acres of sand suspended in the water – as per usual for this area.

We located the central portion of the wreck which appears to be a boiler. (Large tank and condensing tubes.) The boiler & associated machinery does not seem to be large enough for one to drive the ship and appears to have been a steam engine that operated winches and capstans etc.

Further dives in better conditions may help to unravel the identity of this ‘Unknown’ wreck

There were Covid oncelebrations upon our return to Cahore and as the Strand Bar was still in lock down we high-tailed it.

As the reader can see from the image, we are getting somewhat long in the tooth for this game – still, its fun.

Divers log Sunday, July 18 2o21.

We returned to Cahore for second dive on ‘unknown’ shipwreck, possibly Bay of Bengal, situated 2 miles off Roney Point. At HW, in 18 metres, water was a little clearer. We located two anchors with chain and a capstan in their correct position. No large boiler or engine parts visible in situ. Brass fixings protruding from the seabed were visible, but no timber remains detected. Sides of vessel seem to have collapsed (or dragged down) not largely visible. Some coal scattered on the seabed. Some late 19th century broken pottery was also found.

Not conclusive, but these finds would seem to indicate a large iron sailing vessel. The fact that the anchors were not deployed might indicate a sudden sinking, or an uncontrollable ingress of water before the ship sunk. There is no recorded war casualty in this area but such an event, and even having first occurred some distance away, cannot be ruled out. Some further evidence is required in order to arrive at any conclusion as to the ship’s identity.