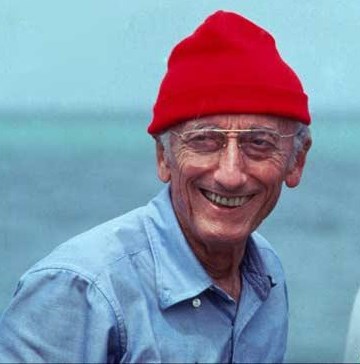

A reader might expect that the familiar image of the celebrated diver and adventurer, Jacque Cousteau, depicted in his red woolly hat says it all. The red divers’ hat, already emblematic, quickly became a fashion statement, but, without any explanation as to why a diver’s head covering should be red.

The association of a red cap with divers is well established now but little tangible evidence exists as to why and when a diver’s head covering was chosen to be the colour red. Its design of course, is forever practical.

There have been numerous explanations, but they all fall short of conviction. The fact that divers wore a head covering is not the curiosity, as any would obviously have kept the head warm or helped to protect the skull from discomfort or injury inside of a diving bell or helmet.

At one time, almost no painting or photograph existed without its subjects having some kind of a head covering

Explanations for the divers’ cap being red, vary. Divers, while sitting helplessly waiting to be dressed, might easily be identified amidst the melee of marine construction, crane lifts and bustling machinery, might avoid injury. This does not seem a very plausible suggestion.

Another, seemingly nearer the mark, suggests that caisson divers spent so much time working in compressed atmospheres that they suffered from decompression sickness, and the red cap could identify them as such whilst staggering about. Construction of the Brooklyn and London bridges being cited.

Sounding a tad boringly pedantic, pressurised caissons were not patented until 1841 and not put into general use in profitable construction until about twenty years later. This makes the earliest newspaper account I have found, of divers wearing red caps in 1842, of interest – read further on.

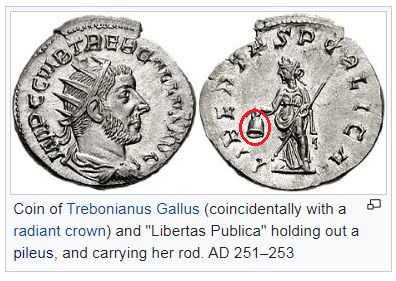

The wearing of red caps was never exclusive to divers. The practice of wearing one is ancient, prevalent in the Middle East and in ancient Greece. Ancient Rome of 210 B.C. and that culture’s Goddess, Libertas, is depicted holding a pileus – a red cap that signified freedom bestowed on slaves. Even the Three Wise men wore red caps.

The symbolism became the ‘cap of Liberty’, or the Phrygian (Turkey) Cap, which was adapted and reshaped by a number of differing nationalities during subsequent years, notably by the French working classes prior to and during the French Revolution in 1789.

This was yet another revolution, when the red cap was worn by French citizens rebelling against authoritarianism and taxes. In 1675 there was rebellion against unjust taxes called, Revolt of the Papier Timbré, during which the Bonnet Rouge was worn. The ‘Bonnet Rouge’ is again represented in modern France as an anti tax or anti establishment movement.

Curiously, during the French revolution the red cap was also associated with the earlier Jacobite Rebellion. Although neither side is known to have worn red caps, except that the concept, Jacobites as rebels, were associated with heads rolling in France.

So, the wearing of the red cap has been in prolonged use as a serious symbol of Liberty or freedom.

Nevertheless, the red headgear was later popularised in literature, folklore and film by its depiction on pirates, fishermen, sailors.

Lifeboat crews of some stations in the Britain and Ireland were known to where red woollen hats.

Its association with the marine remains very strong. The red cap’s association with religion and clerical garb is also strong. As are the colours of other items of religious apparel, demonstrated when the the Rev. Ian Paisley referred to Pope Paul VI as ‘old red socks’.

The cap also prowls into the world of goblins and pookas and was a popular name for race horses and drinking houses – Mother Redcaps etc.

If the redcap was a European thing and not necessarily English, I wonder how did it became prominent in the UK?

William Walker (1869-1918) and his underwater exploits shoring up the foundations of Winchester Cathedral, is dominant in this saga.

Depicted in his suit alongside his helmet and wearing the familiar red cap, seemingly cemented British divers with the wearing of the red cap. Although born in England of unknown parents, Walker’s surname was changed from the likely sounding French – Bellenie, which may alternatively have represented a small village in Norfolk, or even a ‘nightcap’.

Walker’s diving helmet was designed by the famous British firm, Siebe Gorman. Siebe was German and Gorman (O’Gorman) was Irish, making this a truly international affair.

The red cap did not remain a symbol of rebellion in Europe alone, and spread to the colonies, figuring prominently in the American wars. A feature of French support for the colonies against the British was that, some of their combatants were taken prisoner and returned to Britain. Many were known to have worn the red cap upon their return and thus the seed may have been sown in this way.

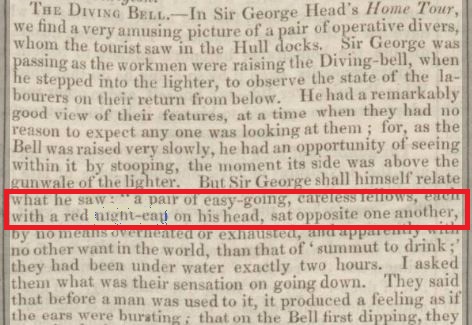

In the Hereford Journal of April 27, 1842 a small article appeared about the operations of a diving bell. (Included here.) The article clearly describes the divers inside the bell wearing red caps. Not just working caps, but what the onlooker believed to be ‘red night-caps’. At least, looking like night caps, as does the Bonnet Rouge or the Red Cap of Liberty. Even so, one must ask; was the red night-cap just to hand or inexpensive, or was it part of the diver’s dress, or were the men rebellious radicals?

Although this report appeared in 1842, it was reporting an event which George Head had included in his book, ‘A Home Tour…’, during a visit to Hull Docks in 1835/1836. So unless the men had just got out of bed, the red night cap was in use by divers even before that date.

It is of some interest that this diving bell was being supplied with air through a leather hose at the time.

It is important to remember that divers are not and never have been, just divers. They are also tradesmen, skilled technicians – workers. When the engineering corps of the British army was formally established, the men were called sappers and miners. 18th & 19th century sappers, (French derivation of ‘trench’.) often employed convict labour wherever and whenever necessary. Their duties came to include diving, underwater construction, wreck recovery and dispersal.

Men, black or white, or even women, civilians or military, who descended in diving bells, were workers, often skilled tradesmen such as masons or carpenters, or just labourers.

Regretfully, we have not been conclusive here. It is my guess however that, French artisans wearing red caps were amongst the earliest ’employed’ divers, and that it is where this association began. Perhaps a trawl through French newspapers might throw some additional light on the subject?

All images are taken from the internet for this not for profit article.

The newspaper article is courtesy of the British Newspaper Archives.