Accurate, but defying an explanation, the announcement as it appears above, was posted in the Custom House, Dublin, on March 31, 1917. Its brevity can be partly explained by war time secrecy, and an importance in preventing the general public and the German navy becoming familiar with British naval matters. The statement did nevertheless indicate an unusual occurrence.

Not lost from view due to violent weather, or struck by a torpedo, and not ‘teleported’, but being a defenceless vessel a long way from the coast during wartime, the worst might have been expected.

Secured by a stout chain to the seabed, five miles off the east coast of county Wexford, one of two lightships deployed to warn shipping of the inherent dangers of the nearby Arklow Bank, the South Arklow lightvessel, Guillemot, and her seven lightkeepers, had indeed ‘disappeared’.

Three days prior to the announcement, the strongly built vessel had plummeted to the seabed, after submariners from the German minelayer UC-65 boarded her, put off the lightkeepers, and with some difficulty, sunk the lightvessel. With the exception of one other such incident, this was, and remains an almost unique event, and has begged the question – Why?

For a while, the general public were completely unaware of the event, and even though the Great War raged, they never seem to have questioned such an unusual occurrence, or even up to quiet recently. This vessel was the only lightship to have been attacked and sunk in Europe during WWI? And only one other occurrence of this kind has ever been recorded.

The other attack also took place during WWI, off the east coast of America, and for the very same reason. This was when U-140 sank LV 71, the Diamond Shoals off North Carolina in March 1918. There were no similar occurrences during WW2 but there were attacks on lighthouses and lightships, not always, but for similar reasons!

(Unlike the Guillemot, the Diamond had her own propulsion by way of a steam engine and a propeller.)

German U-boats in the Irish Channel

Germany’s second ‘unrestricted U-boat campaign’ began in February 1917, and almost brought Great Britain to her knees, even forcing the authorities to consider unfavourable terms for a cease fire. Although Britain on the one hand, had been running out of ships, munitions, food and money at an alarming rate, Germany’s over-optimistic calculations for victory on the other, were dashed, when America entered the war – albeit not until many months afterwards.

New tactics such as the ‘convoy system’, the adoption of multiple routes to France and Britain, utilising large and fast troop carriers, and the introduction of improved anti-submarine warfare methods, were all immediately introduced by the Allies, and soon had the desired effect.

Germany’s growing predicament; its attempt to prevent American troops landing in France, and the Allies new fast track measures of re-supplying Britain, and a growing inevitability of being overwhelmed by a huge fresh army from across the Atlantic, had become a desperate race for victory.

Germany’s U-boat strategy was forced out of the vast expanses of the Western Approaches, and into concentrated areas of the Irish Channel, and its approaches off the counties Antrim to the north and Wexford in the south. The squeeze presented significantly greater risks for the U-boats, but so too, improved opportunities – for a while.

By the end of the year the ‘hunt and kill’ patrols mounted by both sides had played havoc on sailors’ and submariners’ nerves alike, and unfortunately for merchant sailors in the Irish Sea, these had also honed the skills of some U-boat commanders. Some of whom would become the most effective and decorated of the war.

Captains and Commanders.

Having borne the brunt of relatively few U-boat attacks between 1914 and early 1917, the fortunes of merchant sailors in the Irish Channel, were unfairly described as those who were lucky enough to have sailed on a ‘quiet lake’. The situation changed dramatically with the introduction of the U-boats’ new strategy. Mayhem grew in the Channel month after month, until it reached a climax of destruction, but ultimate failure, in April 1918.

It was during these operations in the Irish Channel, that two of Germany’s most highly decorated commanders emerged as ‘Aces’, in terms of the number of sinkings by U-boats in both world wars.

Most notable of the two, was captain Otto Steinbrinck. After commands in U-6, UB-10 and UB-18, Steinbrinck achieved considerable success commanding UC-65 in the Irish Channel during 1917, and later in UB-57. Steinbrinck was later relieved in the Irish Channel by another extremely able submariner, Johannes Lohs in command of UC-75.

Lohs’s first patrol, to the coast of Cork, where he laid all of his eighteen mines on May 3, 1917, would appear to have been equivalent to misplacing a winning lotto jackpot ticket. After the infrequent step of laying all his mines in a single deployment in the approaches to Cork harbour, he then sunk seven local fishing boats with bombs. In doing so, he alerted the first American destroyers about to participate in WW1 of his presence.

Approaching Cork harbour at that time, the mines were exploding, thus warning the approaching destroyers. The action also gave the Admiralty an opportunity to instigate an ever higher state of alert, and avoid the new dangers presented. Sinking any of the American destroyers would have been a propaganda coup for Germany, and extremely embarrassing for America and Great Britain.

Lohs continued his exploits in the Irish Channel during 1917, and was singularly successful in sinking ships.

The Arklow Incident

Commander Steinbrinck’s modest successes during his first patrol in the Irish Channel during February 1917, were soon followed by an extraordinary trail of havoc during his next patrol in March.

The ‘Arklow incident’ began after Steinbrinck, while in command of UC-65 out of Flanders(The ‘Drowning Command’), laid his mines off the west coast of England, and then proceeded to sink ships in the Irish Channel on March 24. During a whirlwind of devastation between the 24th and the 28th, Steinbrinck sunk 17 vessels. He attacked and damaged the ‘Mystery’ or ‘Q’ ship Peveril off the Lizard, while exiting the Irish Channel for a return to base.

After being vigorously hunted by a number of vessels with listening devices, UC-65 evaded detection with countermeasures, such as one we have come familiar with from the movies, ‘silent running’.

His lethal handiwork continued in the vicinity of the Arklow Bank, when he sank the armed Liverpool steamer Snowden Range during daytime on the 28th. It was followed by the Russian sailing vessel “Lagmar” enroute from Cork to Glasgow, and the English and Greek steamers Ardglass and Delgani. (The ship’s bell from Delgani is in the Maritime Museum at Arklow.)

It was whilst stalking his next victim, the Wexford vessel, Harvest Home, that the trouble began. It has long since been reported, that it was at this time, Steinbrinck detected warning signals trasmitted to the Harvest Home and the steamer Annan out of Glascow.And that these were made by the nearby South Arklow lightvessel Guillemot. It is this action by the lightkeepers, which lies at the heart of some lingering controversy.

It must be emphasised that, the crews from the vessels mentioned above, were all allowed to disembark before their vessels were sunk, by either gunfire, bombs or torpedo and that no casualties resulted. This was not always the case, and there were a number of fatalities amongst the crews of the seventeen ships sunk by Steinbrinck. Notwithstanding, Steinbrinck carried a well earned reputation of compassion for his rescue of British submariners from E-22, one of his earlier victims while in command of UB-18.

Although believed by both sides, that is to say, senior British, German and American naval personnel, and at least some members of the light keeping service administration, that lighthouses and lightvessels were to remain ‘neutral’ during the war, Admiralty personnel were installed in some light installations. They and some light keepers, did report on enemy submarine activity, and duly claimed rewards for their diligence.

The reporting of U-boat activity was helped greatly, when the light station had a telegraphic wire connection to land, as several lighthouses and some unknown number of lightvessels had. Some installations were fitted with radio, but this could not be used in an ordinary way, as German submarines could detect warning transmissions made by it, using their own radio.

As well as Morse by light or flag, and unbeknownst to U-boat commanders, each of these methods of communications were used to report the movement of German submarines during WWI.

Detecting submarine activity might seem to have been an impossible task, the submarines being beneath the surface. But if one remembers that, the majority of a U-boat’s cruise was spent above the water, then a light-keeping service acting as a ‘watch’ service, was very useful.

The natural reaction to save life at sea is both understandable and commendable, but more importantly, Germany seen the practise as being a complicit act of war, and a contravention of the ‘understanding’ between the belligerents.

It is ironic that, it was Britain’s enemy, King Louis XIV, who probably gave birth to the light-keepers’ lifetime motto, ‘For the Saftey of All’ in 1697. The great entrepreneurial lighthouse builder, Henry Winstanley was kidnapped by French privateers during construction of the Eddystone lighthouse. When the French King learned of his capture, he ordered his release and is accredited with the message, ‘I am at war with England not with the World’.

The practise of ‘submarine watch’ inevitably placed the lightships and their crews in extreme danger. There appears to be no evidence that the lightship crews refused to cooperate. There is also a small number of recorded incidences were lightship crews rescued German submariners.

Captain Steinbrinck boarded the Guillemot at “6.10 PM on the 28th where he found no secret material on board”. He put off the light-keeping crew with customary directions for the shore, giving the times of local public transport (popular folklore), before placing “two explosive charges” in the bilges.

Before leaving the vessel, attempts were made by the Before leaving the vessel, attempts were made by the submariners to remove the lightvessel’s bell. Unlike an ordinary ship’s bell, those on lightvessels were very large, in order to carry a signal for some distance during bad weather. Germany was three years into the war, blockaded, and running short of valuable metals and materials. Submarine commanders had orders to retrieve scarce metals, such as quality brass, whenever possible. Attempts to remove the large bell failed, and it is believed to be still in the vessel.

Probably due to its stout construction, the “charges only penetrated the shell plate” and the “boat failed to sink”. At this point, UC-65 “dived to avoid an oncoming steamer” after which he surfaced again and sunk the “English government transport Wychwood, laden with coal”. Steinbrinck returned to the “Guillemot at 8.00 PM and sank her with ordnance fire”.

It might not be too difficult to understand what ‘secret material’ Steinbrinck expected to find on the lightvessel, but there we have it, and we are only left to wonder. Whatever the perceptions were on either side, Steinbrinck did punish the lightvessel and its crew in a very rare action, for a perceived infraction.

First-hand accounts from both sides of the ‘Arklow incident’ are presented by a translation of Captain Steinbrinck’s war diary for the 27th and 28th, and recollections of captain Rossiter of the Guillemot, who subsequently reported to the Board of Trade and the Admiralty via the Commissioners.

As Jim Blaney recalls in his excellent article for the Irish Lights in-house magazine, Beam, Rossiter was both praised and admonisehd. Praised for his bravery in warning the ships of the lurking U-boat, and reprimanded for disobeying Admiralty instructions! As these instructions were ‘secret’, the Lords reported view on the matter is hard to comprehend.

It is clear however that visual signalling was reported to have been forbidden, but ‘electric’ signalling by telegraph was not. The men were duly awarded their medals and torpedo badges.

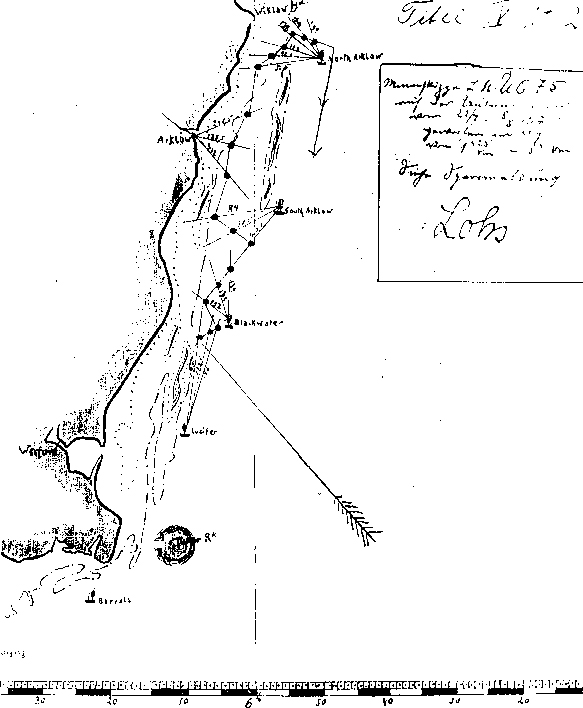

Laying mines off the East Coast of Ireland.

It was also mistakenly theorised by some coastwise traffic that, a degree of protection was to be had from marauding U-boats by travelling inside of the dangerous sandbanks that are situated 5-6 miles off the east coast.

Leaving aside the controversial Kynoch explosion on September 21, 1917, which some still insist was caused by gunfire from an enemy submarine, attempts by the U-boats to bombard shore targets were infrequent, but were a considerable moral booster for the German naval crews, and quite the opposite for the British.

A patrol in the cramped conditions of one of these minelayers usually lasted for two weeks, but could some lasted as much as 3-4 weeks.

Locating and Diving the Lightvessel Guillemot

One of the unfortunate side effects of the ‘Celtic Tiger’ was the demand on divers’ time, which was at a premium, making it difficult to mount wreck hunting expeditions. (Inversely, the consequence of its aftermath is that, divers have now no money, producing the same effect.) Sadly, despite the fact we experienced a prolonged fine summer in 2005, we were unable to begin operations until quite late in the season.

After a number of sonar runs in August, we located an anomaly on the seabed not far from the plotted chart position of the lightship. But it was not until September, that we set off from the marina at Arklow to explore the anomaly in a new 25ft. Offshore dive-boat christened, Quickspin. (Although conditions in this marina and in the river generally, can be quite ghastly, the facility is quite convenient for diving the Arklow Bank.) Consequently we missed the best diving window in July and early August, and had to contend with the inevitable bad visibility.

Differing from the Kish, Bray and other sandbanks, the Arklow and Wexford sandbanks are particularly difficult, where enormous amounts of sand move on a tide, and can remain suspended in the water, making visibility hopeless for long periods of time. These ‘clouds’ of sand can be seen on the sonar, and if unfamiliar with the phenomenon, can lead to some annoying confusion.

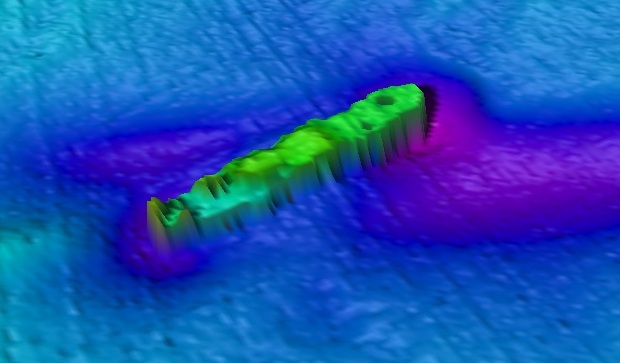

Notwithstanding, the Dublin based Marlin sub aqua club divers visited the wreck of the Guillemot twice. She was found to lie upright with hull intact on the bottom in 53 metres. Based on the limited amount of bottom time, divers’ reports were confusing, but there is evidence of some unusual damage to the hull, high on the port side. Although there was some above deck accommodation to begin with, the divers reported that this practically non-existent now. On both occasions conditions were less than perfect and the visibility was atrocious.

It is hoped to revisit the wreck, in order to determine if her large bell remains in position. It is of course the property of – whom? Perhaps the British government still owns the wreck after paying out for her loss under the War Risk Insurance Scheme? Alternatively, she may belong to the Commissioners for Irish Lights? Interestingly, under the post-war reparation scheme, the German government paid for the building of the replacement Guillemot.

Whoever it belongs to, I’m sure that the Arklow Maritime Museum or the Museum in Enniscorthy, would both appreciate having such a fine memento from a wreck, that was sunk on their doorstep in such controversial and historic circumstances.

Epilogue

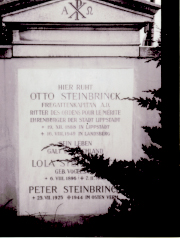

Otto Steinbrinck survived the war and played an active role during WW2. For his honorary membership of the SS he was interned in 1945, but died following an untimely release from captivity in 1949 for an operation.

Commander Lohs assumed command of Steinbrinck’s old boat, UB-57 and was lost with all of her crew, after striking a mine off Zeebrugge, on August 14, 1918. His previous boat, UC-75, was rammed and sunk by HMS Fairy off the east coast of England, May 31, 1918, with the loss of 19 of her crew in controvarsial circumstances .

In one of those rare engagements, UC-65 was torpedoed by the British submarine C-16 in the English Channel, November 3, 1917. Twenty-two of her crew were killed, while Captain Klaus Lafrenz and five submariners were saved.

Returning to the issue of light vessels and lighthouses during WW1, and the fact that their keepers and others present on them, relayed the movements of enemy submarines to the Admiralty, in contravention of what appears to have been an ‘understanding’, which seemingly existed between the belligerents. It may only remain a mute point, whether or not these actions might attract the term ‘illegal’, or that they threatened lives, and contravened the light keepers’ own motto – “For the safety of all”?

Notwithstanding all the historic reflection and interpretations of the causes and actions of the Great War, it is the militarists primary aim to be victorious. To this end, they are known to repeatedly transcend accepted and agreed norms of behaviour to this very day.

Another WW1 U-boat commander no stranger to Irish waters, captain Ernst Hashagen of U-62, may have faced the inescapable reality of man’s rogue gene, when he wrote in his rememberences, ‘The Log of a U boat Commander’, 1930.

“And so the history of this war, too, lives on in us, as an enduring memorial, as a tremendous monument of warning to the nations of Europe.”

Photographs.

Light-keeping crew of Guillemot.

Back row left to right: Unknown, Paddy Cogley, James Sinnot.

Front row left to right: Bob Roche, Captain Rossiter, Martin Murphy, Peter Gaddren.

Courtesy of the staff assigned to the Guillemot in Kilmore Quay.

Captain Otto Steinbrinck

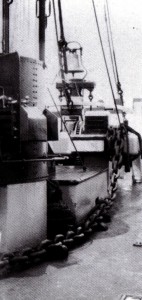

Portrait, tombstone and his boat UC-65, courtesy of U-Boat Archives, Cuxhaven,

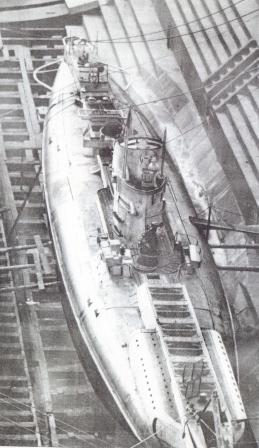

UC65&75 class of minelayer. (German Warships Of Word War 1)

Chart of mine laying off the Wexford and Wicklow coast by UC-75. Courtesy of National Archives, Washington.

Dive boat.

Divers from the Marlin SAC aboard Quickspin after their visit to the wreck of the Guillemot. Against the quay wall in Arklow harbour is the decommissioned lightvessel Skua.

Lightvessel Guillemot, Kilmore Quay.

This is a picture of the light vessel Guillemot (2nd). She was a replacement vessel for the ‘South Arklow incident’ and was paid for by Germany. Her station was ‘Conningbeg’ and later established as a land-locked museum in Kilmore Quay, before being finally scrapped.

North Arklow Lightvessel, Shamrock.

A view of the almost identical North Arklow Lightvessel, Shamrock in 1902. The large mooring chains and bell clearly visible. Courtesy of Irish Lights.

Underwater photograph.

Underwater photograph of UC-65, showing her mine chutes, courtesy of Periscope Publications.

Sonar picture of Guillemot by Irish Underwater Seabed Survey – Infomar.

Translation of UC-65’s log is courtesy of Goethe Institute, Dublin.

Roy Stokes

PLEASE NOTE:- All images, text and video contained in this post, can not be reproduced without permission of the authors or accredited artists.