After all those years. We followed up on every bar-room story, endless tales by fishermen, and all of the mucky folklore that was ever recounted about this wreck – that of a submarine lying on the Arklow Bank. Probably known to many now, a much abbreviated version of the tale goes as follows.

In 1917 the huge munitions production plant, Kynochs, situated on the north shore of Arklow town, blew up, killing a significant number of workers. The subsequent inquest could not arrive at the cause; a number of scenarios being suggested. The IRA, a worker nipping out for a smoke, and that it was the result of a German submarine firing on the plant from the sea. The latter, seeming implausible, then and now, was nevertheless a real possibility in the minds of the Arklow people – having previously seen enemy submarines lying off their coast in wait for the Kynoch’s ships with their bulging cargoes of war material to depart. And it would not have been the first time a German submarine fired on shore installations in the British Isles during WW1.

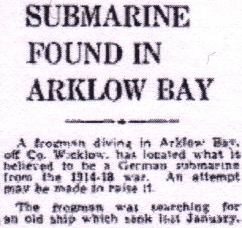

It nevertheless remained a fanciful tail until 1958, when the coaster Anna Toop sank at the southern end of the Arklow Bank – known in earlier times, as The Tail. Salvors were despatched to Ireland to investigate the wreck, and two divers hired a local trawler to search for it, by sweeping a wire. An obstruction was located, and one of the divers went down to investigate. The other, his female colleague, remained on board the trawler! When the diver, a ‘frogman’ no less, returned topside, he reported that the wire had not caught in the Anna Toop but in a German submarine!

This goose was well and truly cooked, when the story was reported in the Press, and for ever more, the population of Arklow could not be shaken from the belief, that there was a submarine wreck on the Arklow Bank. And not just any old German submarine – but the one that blew up Kynochs!

The story of the wire catching the submarine was told to me in 2005 by a crew member of the local trawler, Naomh Eamon, who was a teenager at the time, but remembered the incident clearly, and even more clearly, went he went to work almost immediately afterwards, for the Salvage Association in Liverpool.

Another diver also reported seeing the ‘submarine’ in about the 1970’s, but could provide very little detail, except that it had a ‘rail’, ‘something like a tower’, and ‘twin screws’. Where it was, how deep it was, who brought him to it, etc., were details that eluded his memory. The position of the submarine was believed to have been near what was known, and is still remembered by some fishermen, as the ‘swash’. This ‘swash’, originally represented a deep gap between the southern end of the Arklow Bank and the beginning of the Tail. Traces of which are almost indiscernible now.

Snags & Tales

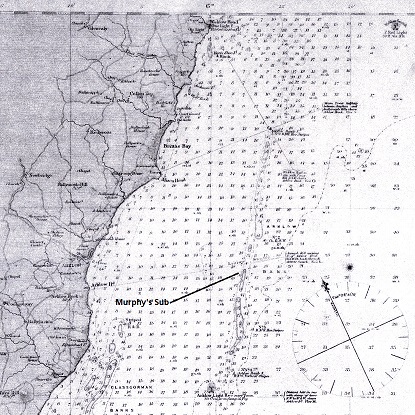

A snag position appears on local fishermen’s’ snag charts for the area, and had been indicated to me by not only fishermen, but by a member of the crew on the tug that had been working on the survey of the Bank, prior to the erection of the wind turbines. This very same snag position was also known to members of the lifeboat station. (A position in these circumstances can be the width of a fingertip placed on a chart. During such enlightenment, such an area, if not already vague and large enough, should not be increased by your own suggestions; ‘Are you sure it was a little bit east or west of…..’)

The problem with all of this is; despite numerous searches in the area – we could not find anything, well, not quite nothing.

When trawlers drag their nets on the seabed to catch fish they often get caught in snags of one kind or another. The one kind we were interested in, was the remains of shipwrecks. In the days before marine electronics and positioning devices, fishermen marked their ‘snag’ in memory, aided by notes made on fishy bits of paper. They for instance, remembered that they came fast in an obstruction when the ‘Little Sugar loaf was in line with the Big Sugarloaf, and Ireland’s Eye had just opened up with the Nose of Howth’. A lot to remember you might say; not tired of that beautiful phrase, ‘on the other hand’, if you were going to lose an expensive net, it would have been well to remember where the snag to be. It was indeed a lot to remember, especially if you consider the hundreds of wrecks that are on the most dangerous sandbanks off the East coast of Ireland.

The ‘Man Trap’

The Banks gained a terrible reputation around the middle of the 19th century when so many emigrant ships were crashing into them with disastrous loss of life. These Banks, with little width that is dangerously shallow, stretch from Dublin to Wexford. Beginning with the Kish, situated just outside of Dublin, they remain roughly the same distance of 7 miles from the shore, for the entire distance. Sloping up gently from the seabed on the west side, and the east side falling off quite steeply, the Kish is followed by the Codling, India, Arklow, Blackwater, ending with the impressively named, Lucifer Bank, off the entrance to Wexford , which was named after the survey paddle steamer Lucifer, under Captain Frazer RN. Another Bank off Dalkey being named after the man himself.

Being such a long way from the coast, it is understandable how counter-intuitive it seems to land-people, when mentioned, that parts of these Banks have ‘dried’ at times in the past, and that it was possible to even stand on them. Even though I have experienced as little as a metre of water on the Arklow Bank, the tales of playing cricket on the Kish Bank seem to push the bounds of a good story somewhat.

Many coastal fishermen fished mainly locally, and those that fished out of Dublin may never have fished any further, than say the Arklow Bank. As time progressed and boats became larger and more powerful, migrational trawling began to increase. When the electronic navigation system known as Decca, was introduced after WW2, marine charts were overlaid with a coloured grid system, lines that represented different measurements and were allocated special radio frequencies that could be received to record one’s position and to navigate by. These were then called Decca Charts. These charts were also used to identify trawling routes and the suitability of the seabed for trawling, and the different species of catch. The radio transmissions were emitted by land based transmitters dotted around the coasts and received by special equipment developed for ships and aeroplanes.

Maybe due to limited access or cost, fishermen created their own charts from the printed ones, using sheets of ‘graph paper’. The radio transmission grid (Green, Red and Purple (UK)) was transposed onto the graph paper in tenths, and used in the same way as the printed one. This cheaper version could easily be copied, and meant that they could just kept marking them up with any new data, such as ‘snags’ – shipwrecks, wigs, plucks etc.

Marine electronics took another leap when the Shadows celebrated satellites with their hit, Telstar, and a new system of positioning at sea was created; Global Positioning System or GPS. It was big stuff at the time, but we now have it in our cars, phones, watches, and if you belong to the ‘1% Club’, you must have it implanted. This development meant that all of the data could be transposed into latitude and longitude and entered into the new system, making positioning and locating positions easier and more accurate. A piece of cake you might say – hmmmmm.

Transposing anomalies recorded on a fisherman’s Decca chart onto the GPS, revealed surprises. Many of the Decca positions, when compared with wrecks and anomalies we had already confirmed, were by enlarge in the correct corresponding latitude and longitude, but many more were not. They were not far away, but surprisingly, on a single fisherman’s Decca chart, the same degree of inaccuracy repeated. When asked, fishermen explained that accuracy often depended on the time of the day and the height of the sun when a ‘pluck’ reading was recorded – the radio waves tended to distort under certain atmospheric conditions. A bit like having to re-tune your radio to strengthen the reception of a signal.

Where Our Team was Coming From

Despite the lack of any historic evidence, in fact, evidence to the contrary, we believed the stories of a submarine on the Arklow Bank, and we wanted to locate it. The initial survey that was carried out prior to the erection of the turbines that are visible on the Arklow Bank today, revealed a number of wrecks, one of which was reported to be a submarine, and was in the position matching that of the fisherman’s snag shown to us much earlier. We had already investigated the area with no luck, but we we would do so again, to be sure, to be sure. We failed, but it wasn’t all blank. We had managed to locate and dive some others, like the Anna Toop and the South Arklow lightship Guillemot. (1917)

The ‘Arklow Sub’ fuss died down for a number of years until the RNLI lifeboat mechanic, Michael Fitzgerald, called with the news that a fisherman who knew where the wrecked submarine lay, and had shown him the position on his chart. The man had not told anyone about it previously, as he did not want eager divers to have an accident diving on it as a result of information he had supplied. (Others considered it a war grave and should not be dived on!)

I travelled to meet Michael, and he pointed to the same position once more. An excited new search began with an expanded area, and covered an additional square mile. Once again, it all ended with disappointment. We did however; detect a large magnetic anomaly about a mile to the north of our search area. Being too far north and producing an obscure and doubtful show on the sonar, it led us to believe that it was possibly the buried remains of the Cameo, lost on the Bank in 1950. This regrettable assumption led to some frustration later.

Believing the task to be that ‘piece of cake’, we were stumped once again when we came to locating the actual remains of the Cameo, which turned out to be a very short distance to the NE of our anomaly. The wreck of the Cameo had been ‘showing’ on the Bank and marked on charts for years, and then no one seemed to know exactly where it was!

We were not really interested in getting into it, but we needed to determine its whereabouts in order to eliminate it from our search, and to avoid confusing it with others.

Renewed Vigour

Armed with our new licences in 2016, we returned to visit Arklow to do some searching – ‘mowing the lawn’ as it is described. This is a great description, as the practise of grid searching can be just as exciting as cutting a large expanse of grass or watching paint dry. Costa is not a sponsor, so I can tell you, that more than one cup does not go down well on a sloppy sea for hours on end!

Arklow is used by Infomar for servicing their survey vessels, so when we saw them gather there, there was no particular interest. Then we discovered that the entire Arklow Bank and inshore bays were going to be surveyed. Obviously, their survey was going to be in a different league to our own, so we ceased ours for a while, hoping to save a lot of Costa, and that we might get access to their results.

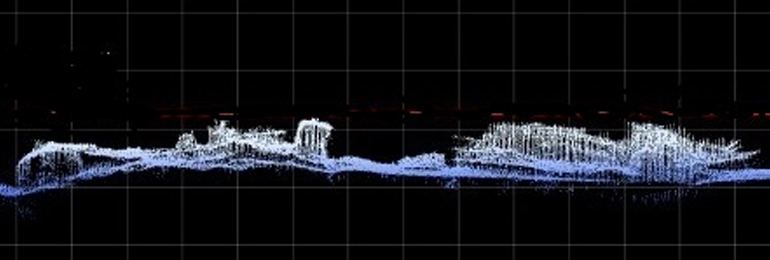

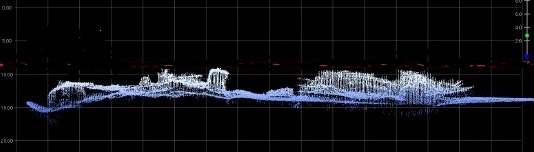

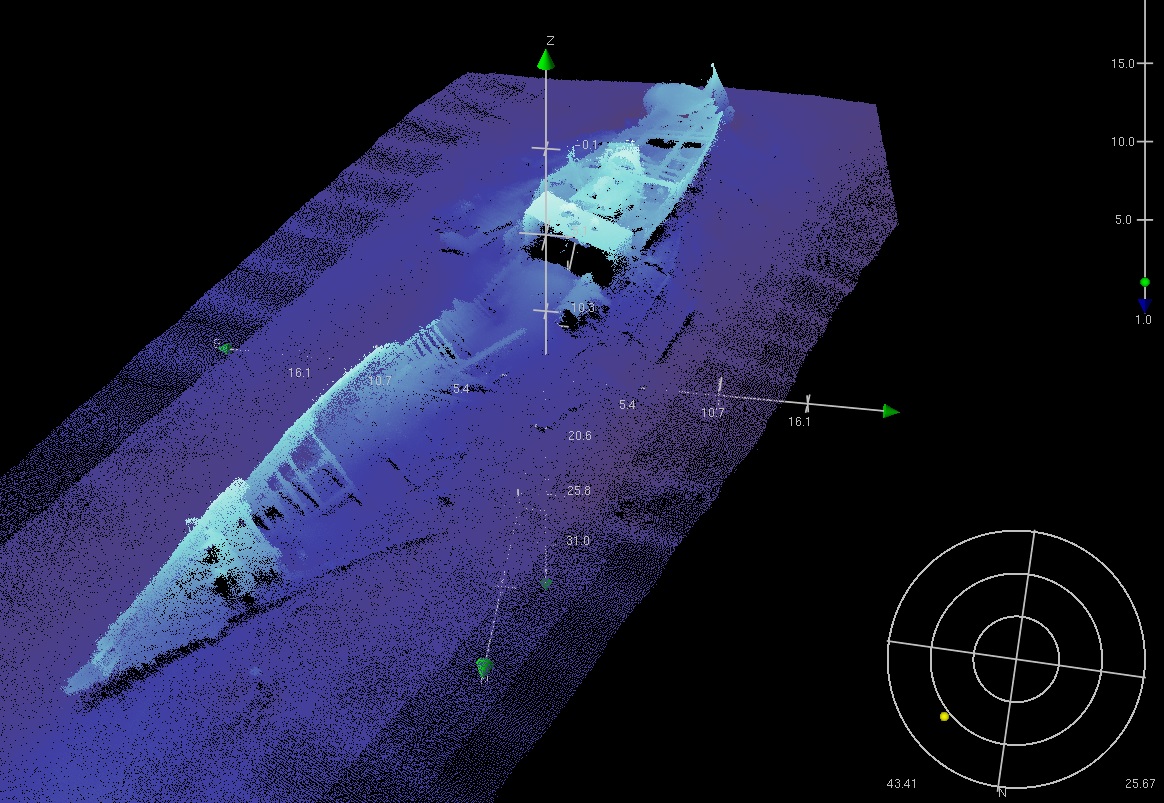

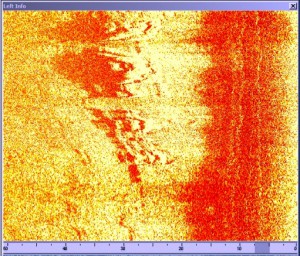

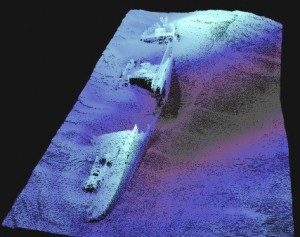

We were shown a sonar image of the wreck (above) and the perception seemed justified – but doubt remained. Infomar continued further passes over the wreck site and built up a spectacular image of what was believed could be the missing submarine.

To rub salt in a festering wound, another call came in from the RNLI lifeboat man, Michael, who had also been contacted with news of the ‘submarine find’. Notwithstanding early assumptions, he was later able to quite cleverly interpret improved images of the wreck differently, to suggest that it was the remains of a steamship with a particular type of engine.

Known in such terms as, ‘The Man Trap’ and ‘Terror of the Underwriters’, there are a number of 19th century steamers lost along the Bank, but Michael was convinced it was not a twin screw Uboat, suggesting instead, that it was the steamer Hellenis. The position of this wreck turned out to be just a lousy 200m’s north of the extremity of our grid search.

Had we been beaten to the location of another lost submarine? Just as with our searches for UC42 many years earlier, we ignored, as we always do, any alarms that tend to manifest during or just after a turn. As the boat’s progress slows, the fish drops, sometimes even striking the seabed, giving a false reading. It’s all that crazy coffee.

Diving the ‘Arklow Sub’

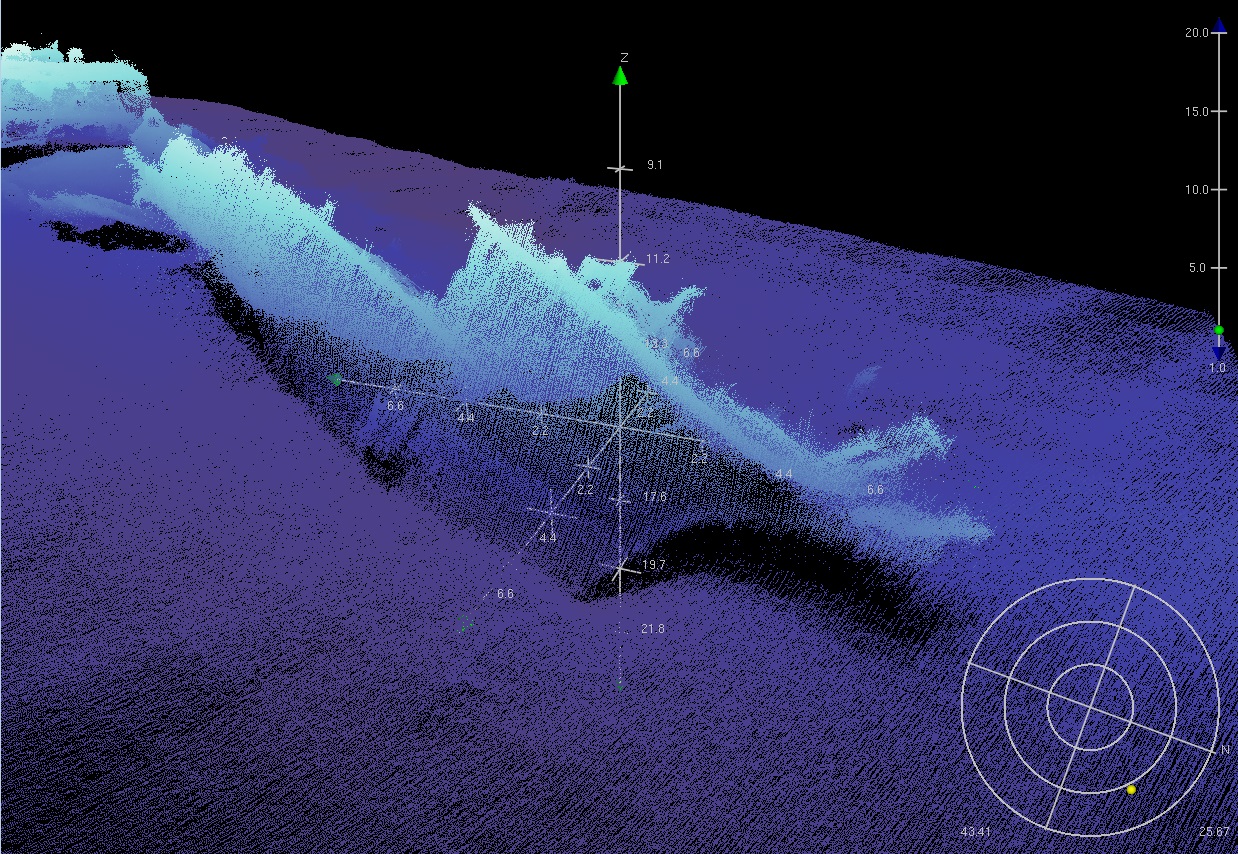

The only way to confirm and identify this latest wreck discovery, was to dive it. In the meantime, Infomar’s survey vessel Keary, had detected the remains of the Cameo and had produced another fantastic sonar image of the wreck. They were unable however to help us confirm the source or form of our first magnetic anomaly that was situated between the two wrecks now discovered.

During September in 2016 we arrived with Ouzel at Arklow for a weekend of diving. Our first dive was on the newly located wreck – Uboat/Hellenis? The wreck proved to have all the hallmarks of the 19th century steamship Hellenis the lifeboat man had suggested. Lying at Lat 52.45.828, Lon 5.57.818 in a pleasurable range of 6-15 metres, it is a wreck that is almost intact, with the exception of the timber elements of the houses that once occupied mid ship and poop areas. Easy discernible is the stern and propeller, boiler, general machinery and a nice schooner type bow with an iron mount for the sprit.

We are uncertain, but there appears to be evidence of some remains of a figurehead. The hull on either side of its cargo holds has collapsed outward, or more probably, as there was no subsequent wreck auction advertised, it may have been pulled down by later salvors. It is well known that salvage companies roamed these waters in search of opportunity after both World Wars.

The ‘Unknown’

The second dive target was the large ‘unknown’ magnetic anomaly at Lat 52.45.960, Lon 5.57.804. This proved to be the remains, bottom timbers only, of an old sailing vessel that still had its cargo of bar iron lying in position on top them. There was nothing else visible and the dive was short – shallow at 13-14m’s.

The Cameo

In the position, Lat 52.46.058, Lon 5.57.490, her remains presents a very nice wreck dive, typical of what a diver would expect of a modern vessel.

Library image of Cameo on Arklow Bank

Library image of Cameo on Arklow Bank

Much of the bow, middle section, and stern are exposed and still intact, except for all general types of upper works.

Sonar image of Cameo by INFOMAR

Sonar image of Cameo by INFOMAR

The tide can be quite strong over the wreck and a diver should be careful not to get himself pushed into where it might be hard to get out of. There is just a few metres to the shallowest part and deep scours to 16 metres alongside. Slack water ‘between the tides’ (couldn’t resist) is pretty consistent with the relativity to the local tidal predictions and is quite lengthy at low water.

Unlike the excellent water clarity along the east coast in 2017, it can only be described as terrible the previous year, but exciting.

Murphy’s Missing Submarine

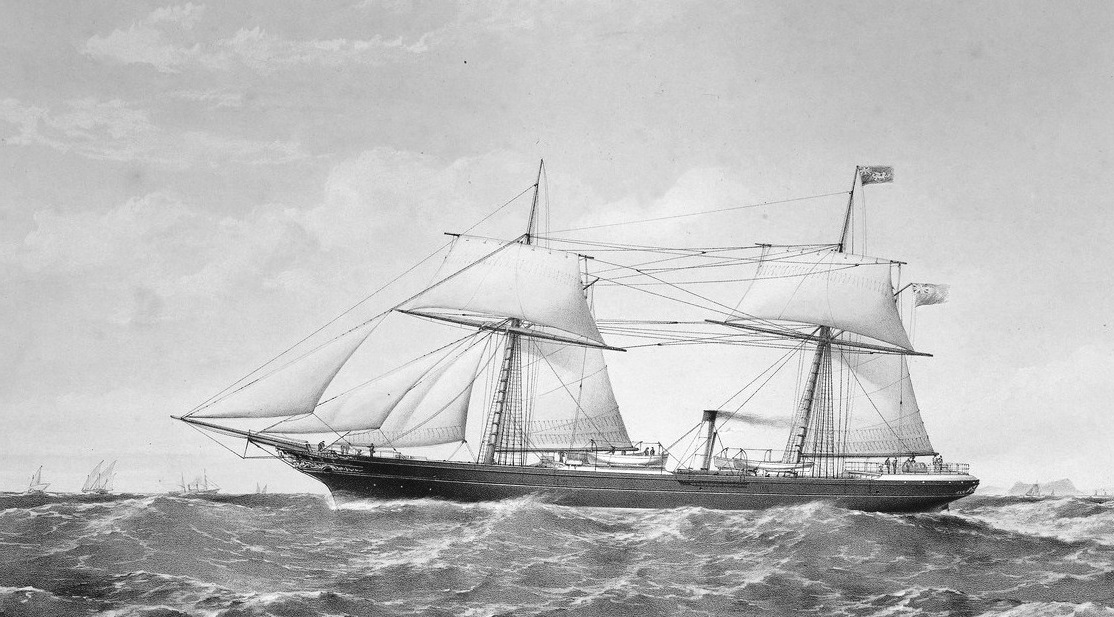

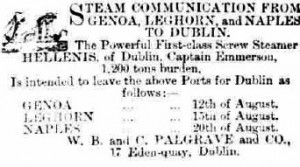

The steam ship Hellenis and her sister ship Ann were built on the Tees by Richardson, Duck &Co. in 1861. Not described as a sister ship, but the very similar Corcyra was also built at the same yard at the time. The ships were built for the Anglo Ionian Steam Navigation Co.. The usual construction accolades rained during the launch of the new ships, except in this case, they were well deserved. One can see from the print of the Hellenis, that she was indeed a very nice looking vessel for its time. She had first class accommodation for 22 passengers in the central saloon, and aft housed officers and second class passengers.

The AISN Company was wound up in July of 1869, and its steamers were laid up in London. Michael Murphy II purchased the Hellenis and it immediately sailed for Dublin in preparation for a voyage to the Mediterranean.

The Hellenis left Dublin for the Mediterranean on August 12, and later adverts indicate that she left on the return journey from Naples on September 3. After leaving sunnier climes, telegraph would later deliver the shocking news that her first round voyage had ended in disaster on the Arklow Bank. After touching at Lisbon, she reached the Tuskar at about midnight on September 15, and then proceeded north, inside the Banks, during the early morning. After observing the South Arklow light and then the Wicklow Head light, captain Emmerson gave instruction for a correction to the helm. Soon after, the ship struck the Bank and never got off.

Ships at the time, had a tendency to take the more risky inside-the-Banks route to save time, and ships still do. The remarkable sophistication of modern navigational aids might very well suggest that you could navigate with your eyes closed, and judging by some of the surprising ‘accidents’ involving huge modern ships in this area today, maybe they do.

The wrecking ordeal was a frightful event for passengers and crew, and part of the cargo – some of the cattle that were thrown overboard, but the Arklow lifeboat performed a splendid rescue, and there were no human casualties.

The Hellenis was registered to Palgrave & Murphy in 1869, and it was stated by members of the Official Enquiry into her loss, to have been the property of Michael Murphy of Dublin. This time the compass was not blamed, but captain Emmerson quite correctly protested to his enquirers, that the South Arklow light vessel had been moved and that no one had told him. This, he claimed, had affected his navigational calculations when making passage inside of the Bank. He got short shrift from the board of enquiry, when they failed to accept ignorance of the fact as an excuse, and suspended his ticket for six months.

Points of interest.

Barring some nice exceptions, many of the shipwrecks on the Arklow Bank fall under the State’s 100 year rule, and a licence to dive them must be obtained from the authorities. Refusals are rare.

The Arklow Bank, west and east of it, is paved with shipwrecks. I have been diving there, on and off for well over twenty years, and I have never met another sports diver there – I have often wondered, why?

It is plain to see that the quality of the data and imagery being brought to the public by our national seabed surveyors at Infomar, is of the highest quality, and deserves the highest praise. Given the quality of surveys, data returns, and imagery that is continually emerging, it is becoming less imperative for amateurs to ‘mow the lawn’ and even to dive to these wrecks – but the thrill still remains. It may yet be called, ‘Desktop Wreck Hunting for Dummies’.

Infomar’s 10th Anniversary Conference takes place in Liberty Hall, October 6/7, 2017.

Histories of the shipping company, Palgrave Murphy, and of the Shipping Murphy’s, fail to mention the Hellenis. This may be due to the fact that she was in the ownership of Michael Murphy and the Company for such a short time.

Any part of this article that is subject to copyright cannot be reproduced without permissions.

By, Roy Stokes & the Ouzel team, Keith Browne, Phil Doyle, John Peare, and Arthur Smith.

PLEASE NOTE:- All images, text and video contained in this post, can not be reproduced without permission of the authors or accredited artists.