‘Render Unto Caesar…’

The Christian Bible is clear – citizens must pay their taxes, just or unjust. Dogma is one thing, in practice, evading punitive taxes has been with us since the earliest success of both. Free-trading, free of taxes, comes in many guises today and is constantly responding to market forces. Illegal gangs of free-traders remain one side of the legal-traders’ coin.

An eruption of ‘piratical privateering’, as it was described, began in in 1779, when American privateers began to attack British and allied vessels in their home waters. The American War of Independence was entering a critical stage, and privateers on all sides were criss crossing the Atlantic in pursuit of victory and fortune. Already endowed with a fearsome reputation won by his exploits in the ship Ranger, when cries of John Paul Jones and his pirate crew in Bon Homme attacking British ships around England and Ireland rang out, it was time for the Royal Navy to roll out the big guns.

At this point, either by design or opportunity, smugglers from the coastal villages of Rush & Skerries in north county Dublin, jumped on the band-wagon of fear and confusion – and made hay. A number of legendary figures were entered into maritime history, but few as notorious as those from north county Dublin, such as the likes of Luke Ryan, Pat Dowling, and John Kelly. Even though they were loosely described as piratical privateers, pirates, corsairs, and all manner of low-life, the difference in terminology became very relevant when it later became Luke Ryan’s turn to stand in the dock. ‘Till then, everyone had been going about a business considered legal’ – actions in time of war, against their enemy, and friends of enemies.

John Paul Jones was a Scot who sailed in American and French ships, Luke Ryan and Dowling were in Irish and French ships, all had letters of marque from either side, and some from both, granting permission to attack and plunder enemy ships. Britain endowed all manner of private ships of war with ‘letters of marque’, and so too, participants on all sides. It was really another Happy Time; when merchants with political allegiances and agencies around the world considered to be operating businesses that were ‘fluid’, could tool up a private ship of war, tout for shares in the venture, and go make a fortune, at the same time receiving plaudits for defeating the enemy. It was also a time for brave men and wealthy merchants.

The war in America and the extent, to which the cruises of American flagged privateers increased around Britain and Ireland, caught the English Navy at a bad time – a shortage of men and ships. In part consequence, full use of private warships was exploited and recruitment went into overdrive. The practice of free-trading, a more honest description of what was widely called smuggling, expanded into the gap left in home security, and began to flourish. The Preventative Water guards and the Revenue men were hard pressed to make any impression on the free-trading and some even participated in it. Outside of the fashionable towns and cities, a kind of free-for-all took hold.

It was uphill for the Revenue men who reported: ‘That smuggling was never carried on with such spirit or such success or on so large a scale as lately on that coast. They are also informed that this the reason to suspect that a pernicious correspondence is kept up between the smugglers and some of the officers of that Port’. (Cork)

Rush & Skerries Boys

Originally funded and launched by Dublin merchants in 1778, Luke Ryan and his motley crew from the fishing villages of north county Dublin took command of the newly fitted-out privateer Friendship in Dublin port. Already armed with a Letter of Marque from the British crown, shortly afterwards he jumped ship, if you will, changing allegiance to the French crown. The ship was renamed Black Prince and began privateering under a Franco – American flag.

In 1779, during a privateering come smuggling trip to his old stomping ground near Lough Shinny, between Rush and Skerries, the infamous Black Prince was captured and the crew were locked up in Black Dog prison, Dublin. Aided by their associates, they managed to escape and made their way down the Liffey in Rush wherries. They recaptured their smuggling cutter, which was still at anchor, and under guard at Poolbeg, Ringsend.

It was a brazen attack on the establishment that seemed completely outwitted. Horatio still had two good eyes at the time, but it seemed more than just a suspicion that there were a number of others in the services suffering from defective eyesight. The Royal Navy had had enough, and let loose a couple of frigates in pursuit of what had become an audacious small fleet of smuggling privateers, with American colours. So began a determined and sustained campaign against the piratical privateers in the Irish Sea and thereabouts. That bout of privateering ended when Britain agreed terms across the Atlantic. Smuggling was reduced to more acceptable levels, but the free trading continued. And as everyone knows – continues in many guises to this very day.

The story of Luke Ryan and his associates, smuggling, and the inhabitants of north county Dublin’s prowess in sailing, boat building and maritime skills has been told. But little is known of the smuggling that took place to the south of Dublin and along the coastal borders of Wicklow. Almost inexplicably, all of the smuggling notoriety in the region of Ireland’s capital city, Dublin, in the 18th and 19th centuries, is focused on north county Dublin. This is in contrast with the so little known about activities of the piratical marauders beyond the Five Arches, between Bray and Wicklow, and at the Brandy Hole in Bray Head.

At that time there was very little evidence of smuggling activity at Wicklow. Almost none was reported, which is not the same thing, as there being any. Was it then that these ‘piratical marauders’ may have been the ‘Rush and Skerries Boys’ from north county Dublin, still active in the Channel, or did Wicklow have their own scoundrels?

‘The Piratical Marauders Between Bray and Wicklow’

The market town of Bray is the most northern coastal town in the county of Wicklow. A place of considerable antiquity, much evidence of it lost. It was an ancient demarcation of the civilised lands of the capital to the north, and the wild mountainous lands of Wicklow to the south and west. The five (Was four.) arched bridges from Little Bray on the Dublin side over the Bray River, stood as border post between lawless nationalism and the civilised seat of the Crown in Dublin.

Both sides were guarded by ancient castles. One to the south in Oldcourt, and one on the north side where the CI an RC Churches both stand, and both long gone now. There is strong evidence that the scholar mariner, St Patrick, landed here, and remained for a number of days. Fine houses and demesnes were established on both sides, policed, and subject to the laws of Britannia, but there was no denying that the county beyond the town was infested with a hotbed of insurgents, or at least that’s how it was seen.

The term ‘piratical marauder’ did not appear in either British or Irish newspapers until 1783, when a rich East Indiaman, Comte de Belgioioso, owned by the Habsburg Monarchy, was wrecked on the Kish Bank off Bray Head. The term was hardly ever used again. Early attempts to salvage a rich cargo from the wreck, ended in the death of the Scottish divers, Charles Spalding & Ebenezer Watson. Syndicate owners of the vessel and its cargo, hired some Moors from Africa to have another go. They were getting on fine, anchored over the wreck recovering various pieces of wreckage, but were dogged by the ‘piratical marauders from along the coast between Bray and Wicklow.’ These marauders were said to be removing the buoys from the wreck, which as every salvor knows, placing them, is an essential and time consuming operation. They were also suspected of removing chests of silver, which were believed to have had buoys attached, making them easier to locate and recover in the event of sinking.

Coffee House Banter

A similar term used to describe licensed marauders did appear at the height of the rampage of privateers, operating between the coasts of Ireland and England in 1780 – ‘piratical privateers’. Even then, there were almost no reported instances of smuggling anywhere near Bray. However, one could easily discern from the newspaper reports, that privateers and smugglers were repeatedly being mentioned, ‘off Bray Head’ or ‘off Wicklow’.

Not being mentioned in newspapers, were the reports in Revenue files eluding to a group of men, led by a ‘notorious smuggler’ by the name of Murray, who were operating between Ardenary at Wicklow Head and Newcastle, south of Bray Head.

Such an incident had been in progress during the summer, but only reported on July 22, 1780, when a privateer lugger was observed ‘close in with Bray Head’. Reports worded in this way were almost code, and had a tendency to put the authorities on guard. When an unidentified vessel was observed failing to maintain a regular course and speed, or ‘hovering’, a punishable offence (Loitering with intent in modern jargon.), they were considered suspicious. Offloading smuggled goods or maneuvering in wait to make a capture, in other words.

This particular detection had included one of two privateer luggers who were in company with the Black Princess and Black Prince, manned by colleagues of Ryan & Dowling from north county Dublin. They had had been raiding down south, and were making their way up the Irish Channel. This Dunkirk lugger was the Mayflower (Le Fleur MaiJ), captained by Pat Dowling (Confusingly, it was reported later, to have been captained by John Kelly, Grumley or Grumlé) from Rush. It was earlier reported by Revenue staff that spies from the privateers had been landed at Wicklow.

After whatever business she carried out close in with Bray Head, the lugger altered course to seaward and later attempted to capture a cross-channel packet-boat. The attempt failed and the Mayflower was soon being pursued by HM frigates, Nemesis and Aurora, stationed in the Channel for this specific purpose. The Nemesis was captained by R.R. Bligh (Apparently no connection with William of later Bounty fame.) and the Aurora, by Henry Collins.

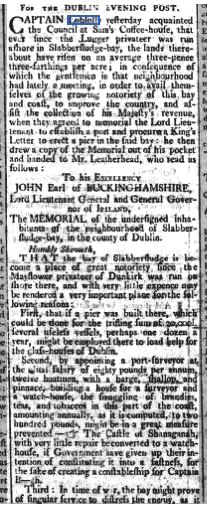

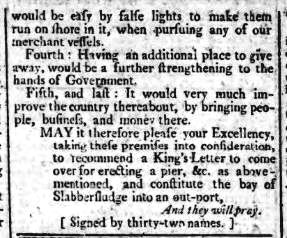

The Mayflower was fired on by the Aurora and chased into a place reported as, Slabbersludge Bay, near Bray Head. Embarrassing the authorities in their own back-yard once again, Dowling and his crew made their escape and headed for Dublin city. A place called Slabbersludge in Dublin, Wicklow or anywhere else in Ireland for that matter, is not known. A misspelling you might suspect, but given its uniqueness and that it continued from paper to paper, which was oft the case in any event, it appears to suggest something in keeping with the tenor of a subsequent article. It never appeared in a newspaper before then or afterwards. Subsequent reports were more enlightening and described the incident as having occurred in ‘Killeny Bay’, ‘Killiney Bay’ and on the southern shores of our Bay.

Sam & his popular wife’s Coffee House in Essex Street might have been serving more than just coffee, if some of the yarns are true.

..Next her bar’s a magic chair,

Oft I’m charm’d in sitting there;’…

Whether the use of this place name was intended as a derogatory slight on some of the gentry or lands about Bray is unknown. At the time, the Bray River was much broader than it is today, and had a shallow island in its center. This, and an area on the north side of the river, called Bray Common, was described as a ‘stretch of marshy floodplain river’ and that the river ‘meandered over a waste of moory strand and cut its way to the sea through a shelving and pebbly beach.’ Given this description and its geology, Slabbersludge seems like a pretty close description, but apparently, not a place-name before then or since.

The Mayflower incident, demonstrating once again how easily these men could escape, produced some mileage in the Press. Some editors valued their freedom more than others, and there were those who could produce fair reporting and were also minded to report some of the anti establishment banter enjoyed in the coffee-houses of Dublin. The tone of the accompanying article is not typical, but not infrequent, neither as a swipe at the ineptitude of the Crown, or at wasting valuable taxpayers’ money. The tax-payers referred to in this instance, being merchants. It is interesting that the coffee-house notice-letter refers to captain ‘B-gh’, presumed Bligh, which was apparently not the infamous William, but probably Robert, a man of some ability and determination mentioned earlier.

The Mayflower was auctioned and sold for 510 guineas at Dublin a short time afterwards, and the proceeds distributed among the capturing crew of HM ship Aurora. There was a suggestion that it may also have been shared with two others. These would have been R.R. Bligh and crew of the Nemesis and James Wilson of the Revenue cruiser Langrishe, who lent a hand when he moved in his pinnace through Dalkey Sound in pursuit of the Mayflower.*

*Fortunatley the log of the HMS Aurora survives in the UK Archives at Kew, and the following is a synopsis of the entries regarding the Mayflower incident.

The Aurora, in company with a number of other vessels, including the frigate Nemesis, left Spithead on July 11. They patrolled the south coast of England performing convoy protection duties and challenging any ‘strange sails’. They rounded the Lizard on the 28th and patrolled north off Lundy, Wales, and anchored off Anglesey on August 3. They proceed west and anchored off Lambay Island on the 4th.

At 4 AM, weighed and made sail, parted company with Childias sloop & pilot cutter, at 6 made sail and give chace to a lugger in the NW, strange sails blow & aloft…’

On the 5th.‘…still in chace of the lugger at 2 PM. fired a number of guns to bring her too, hoisted out all our boats, Mann’d and Arm’d in order to board her but she runs ashore before we could come up with her she proved to be the Mayflower Privateer from Dunkirk…’

There was no specific mention of Killiney Bay and the Aurora anchored with her prize in Dublin Bay alongside the Nemesis. The cruise continued in a similar vein as far as the Waterford Estuary, making a return to England on September 13. The reason for the bad Irish Press may have been the action by British warships off Dublin or may have been that they boarded a number of vessels in the Bay in order to press gang additional crew.

The Head & Smuggling

As Bray had little or no history of ship building, over and above what any other coastal village had for small fishing boats, it was unusual and coincidental how twelve months after the Slabbersludge incident, in September 1781, a privateer cutter was fitted out, pierced for 20 guns, and was launched at Bray. This privateer was prepared for cruising but no details of her ownership or name were given. The incident which the piratical marauders, who supposedly existed between Bray & Wicklow and had raided the wreck site of the Belgioioso, followed in the summer of 1783.

And for a town and even a county, that had some reputation for smugglers, it is surprising that there were no further newspaper reports on the subject until June, 1789. Hovering off Bray Head, a Revenue cutter seized a smuggling wherry, but not before local boats from Bray had taken off the cargo of geneva, tobacco and silk and spirited it into hiding places ashore. The wherry was captured and brought to the Custom House in Dublin. Reports of smuggling around Ireland remained prevalent, but few at Bray.

The Revenue men still had their spies and believed that a smuggler by the name of Murray was known to live on a farm north of Wicklow. Not reported, they recorded in their ledgers that the ‘noted smuggler Murray’ landed goods at Newcastle and transported them to Dublin in January 1802.

Again in June, six years later in 1805, alarm was caused by a smuggling cutter observed under Bray Head. Apparently the cutter refused to be hailed by a Revenue barge and threatened to fire on its enquirer. As it turned out the cutter was a prize to HMS Pelter, and was seized earlier at the Arklow Bank. The prize crew on the cutter were guarding their seizure and proceeding with it to Dublin.

Smuggling continued everywhere, and anti smuggling measures were bolstered in 1805 with the introduction of additional legislation, the Smuggling Prevention Bill. Like all previous and subsequent measures, the smuggling continued. Notwithstanding, there were still remarkably few reports emanating from the coast of Wicklow. It was not until 1822 that a serious case of smuggling occurred, or at least, was reported from Wicklow – occurring near the coastal village of Kilcoole.

Kilcoole, and alternatively, Grey Stones, were described as the place where a smuggling vessel drifted towards a blue light on the shore. The Revenue men, having no shortage of spies and informers on the payroll, who were also known to get a ‘cut’ out of the value of any seizure, the smuggling vessel was expected by both parties. Those who turned up to receive the goods, and those who turned up to catch them.

Twelve carts and a number of men and horses received 40 bales of tobacco from the ship before she disappeared into a veil of darkness. A number of the Watch Guard (Preventative Water Guards) emerged from hiding and a melee ensued. It was reported that the Guards were attacked by 300 local people but were repulsed, and that nine men were arrested and the tobacco seized.

The men were transported to Dublin but couldn’t be prosecuted, as they were from Wicklow and out of jurisdiction. The men were returned to Wicklow town for trial. They were all found guilty and sentenced to be transported for seven years.

The accused were; John McCabe, James Booth, Thomas Gregory, John Connell, Patrick Grace, Michael Stanley, Anthony Pluck, John Castles and Mathew Knackler.

Despite the audacity and size of the seizure at Kilcoole, the free-traders’ opportunities were coming to an end. Colonial expansionism was on the back burner once again, and lots of experienced sailors were idle. The Preventative Water Guard improved and was replaced by the Coastguards. The death knell of widespread smuggling finally rang when governments reduced taxes under their own competitive policy of free-trade. Although in many respects, even though the practice was dying, smuggling continued. It was, as with all commerce, adjusting.

The next instance of any note concerning a smuggler off Bray Head was reported two years later in 1824. Again in February, a notorious month for bad weather in the Channel, HM ship the Essex having left Plymouth, was proceeding up the Channel, when she took up the chase of a smuggling lugger. The Essex eventually crashed into the smuggler and dropped her gun ports, threatening to fire. The lugger surrendered and was brought in to Kingstown. (Dún Laoghaire) As it happened, the Essex was proceeding to take up her station as a prison ship in Kingstown, and was unarmed – not a ball on board. This first report of the incident was claimed to have been false, in that the Revenue cutter Dwarf, had also chased down the lugger and the Essex was just in the right place at that time – but faster. On a technicality, the Dwarf was claiming the full value of the prize, so it went to the Admiralty Court.

The lugger, the Two Sisters from Holland, had been carrying 1000 bales of tobacco, 75 cases of gin, gunpowder and tea. I wonder who was taking delivery of that lot. The Two Sisters was moved to Dublin and the cutter Dwarf sank during a gale in Kingstown the next day. It was reported that the commanders of the Essex and Dwarf would get between £1000 – £2000 each. Becoming rare, the incident was described as an ‘Extraordinary Capture’, and it marked the end of the few known incidents of smuggling around Bray Head – until.

Twenty years passed and steam travel brought a railway to Salthill, Monkstown. The new harbour at Kingstown demanded an extension of the rail to the center of the harbour opposite the Forty Foot road. A further extension was demanded to serve the New Brighton of Ireland at Bray. The railway caught on, and was being demanded everywhere. A further extension was planned for along the coast to Wicklow and Waterford, but the obvious and cheaper route to the west of The Head, through the magnificent Kilruddery Demesne, could not be secured from Lord Brabazon. He eventually agreed to a precarious route around the seaward edge of Bray Head, and work began in 1847.

The Story

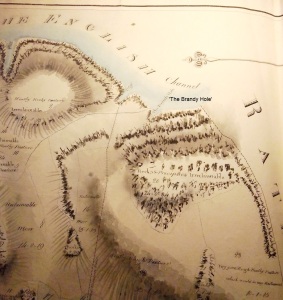

The first sod of the new line was turned, and without hardly a remark, the excavation and tunneling for several miles through rock around The Head, demolishing the large smuggler’s cave so ‘familiarly known for its lawless occupation by smugglers’, called the Brandy Hole, was reported in the Press. It was in fact, the first time in the British Newspaper Archives, an extensive database of newspapers and magazines, dating from 1700, that this Brandy Hole was mentioned.

**See note for mention of Brandy Hole on Kilruddery Estate map.

The British Isles is teaming with Brandy Holes, and I daresay that all of them are associated with smuggling, as is the one at the rear of the cottage ‘Castle View’ in Bulloch, Dalkey, belonging to boat-woman, Monica Smyth.

Despite its previous lack of mention, everyone in the vicinity of Dublin seemed to have been aware of the notoriety of the one in Bray Head. Although it is shown on the 1838 ordnance survey maps, it is not shown in the place where it has become known today. Previous mention and omissions are even harder to explain.

A juncture had arrived when there had never been any previous mention in the press of a smugglers’ cave called the Brandy Hole at Bray Head, but after which, books and stories were written about a world of smuggling that existed there.

This awakening would seem to have been due in large part to the writer Campion, who was a naturally curious man, and was considered to be a romantic nationalist. Born in 1814, he often just signed his work, J.T.C., but was in fact the writer and prolific Kilkenny poet, John Thomas Campion (Dr), and probably the same man who described himself as ‘A constant reader and a real friend of progress’. Campion trained as an apothecary but did not become a medical man until 1860. He was a regular contributor on literary and philosophical matters, a fine poet, and was considered a ‘true patriot’ or an ‘ardent Irishman’, as he would describe himself. He died in 1898, leaving behind the remarkable tale, ‘The Last Struggles of the Irish Sea Smugglers’, published in 1860c. In it he describes the operations of a group of smugglers that occupied a large sea-cavern in the base of Bray Head, called the Brandy Hole. Although described as a ‘romantic novel’, the place has gone down in folklore, and has been mentioned by almost everyone who visits or lives in the town of Bray in Wicklow County.

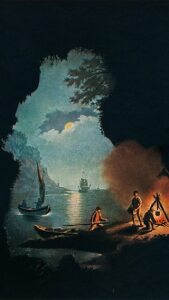

The story was later reworked in The Weekly Freeman by a later writer, an ‘old colleague’ of W.B.Yeates, H.T. Hunt Grubb. Most people today, and even after the Bray to Wicklow railway development, supposedly demolished this notorious smugglers’ lair, believe that a basis for the story exists. Campion describes in some detail the large cavern, its two levels and access to it by sea and a cave on the upper level. He also described how the entrance to the large sea-cave was marked by ‘Coon Rock’, which is probably the anglicised version of Cuan Rock – meaning bay or harbour, and how the local smugglers rendezvoused with smuggling ships there.

Campion certainly knew his setting. He had been an apothecarist and a medical doctor, living in Dublin, and may have seen himself as the sympathetic old naval ‘Doctor Fry’ in the book, who lived at Navarra Avenue, Bray.

It may be only a coincidence, but Murray is a significant figure in J.T.C’s story. It’s an adventure, a love story, a reflection on the times past and present, and in its case, maybe truth is stranger than ‘romantic fiction’. We’ll see.

Remains of the Brandy Hole

The Brandy Hole story first came to my attention during a pub crawl, believe it or not. Just a couple of guys out for a drink at Christmas in a wonderful old world tavern, called the Harbour Bar. Situated beside the Martello Tower just yards from the seashore in Bray harbour since the 19th century, it appeared to have hardly ever changed. Stone floor, dusty recesses, nauticalia hanging from the rafters, and no quarter given to ‘progress’. Home to some remarkable curiosities, it was once a meeting house for members of Freemasonry.

During the festive imbibing, I spied a beautiful model of an old smuggling brig in a corner, supposedly a representation of the smuggler which had supplied the nearby Brandy Hole with contraband. The story sheet was laid out inside the glass-case which was owned by Mr Loughrey (RIP) of Bray. The model has since been removed to its owner’s residence but the pub is still there and well worth a crawl.

The only obvious way of possibly authenticating such a story, was to try and locate any remains of the large smugglers’ cavern that might still survive in the The Head. It was described as been been so large, and on two levels, that maybe the progress of the railway hadn’t destroy all of it.

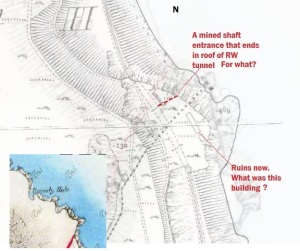

Brandy Hole tunnel with building on sea side and white line marking track to cave. (Image courtesy of Gary Paine.)

If the old images included here are to go by, there was considerable blasting at the Brandy Hole, in order to elevate the foundation for the bed of the railway from the sandy seashore. Just one of the blasts at the site might have the accomplished this, when it hurled down 1500 cubic yards of the adjoining cliff into the sea to the applause of ‘some hundreds of spectators’ in February 1849.

This area has been beset by the forces of the sea and rock slides for years, the rail line having been moved in several places and protective rock armour added a number of times.

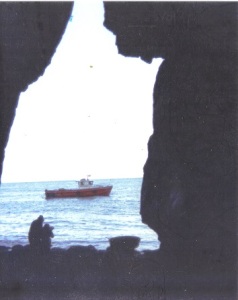

If one is to avoid reprimand from the railway authorities, the best way of approaching the Brandy Hole, the ‘Second Tunnel’, is by boat. With my diving buddy, Jimmy Elworthy, we set out in our boat one fine day many years ago to have a look. After anchoring off the Brandy Hole, we rowed ashore in a punt. Nearing the shore, the entrance to a previously unseen cave adjoining the tunnel came into view. We rowed into it, got out, and walked around the inside, having a good look around. It was a very large cave and you could certainly get a number of boats into it. However, it just didn’t seem right, and although the back of the cave had fallen in, it had no obvious exit. When we got back to the boat we made the tea and had a chin wag about our discovery.

Sometimes your eye might follow a bird, or attracted by a movement of shadows, the sun going behind a cloud, but as we were gazing at the cliffs, suddenly a hole in the side of the Brandy Hole Tunnel became visible – it was without doubt a dark hole – a cave entrance, but it seemed inaccessible. We had to return to the harbour, but for sure, we would be back.

On a later expedition with Jimmy, we walked along the seashore from the Bray esplanade until we reached the tunnel. There was no way of accessing the cave entrance from the railway on the north side of the Brandy Hole Tunnel, so we proceeded through the tunnel until we reached the southern side. Taking an obscure narrow animal track around the outside of the tunnel on the seaward side, we passed through the remains of foundations belonging to a small unknown building.

Several yards further on we reached the edge of the sea cliff. It seemed like we could go no further. But on closer examination, we discovered an even smaller track that was no more than 14 inches wide, leading on and around the cliff face. We edged along it, lying in to the cliff face, and suddenly there it was; a cave – a man-made cave entrance. What could it have been?

Delighted to be off the narrow ledge, we worked our way into the recesses of the cave, gradually getting darker, until there was a little brightness ahead and then a sudden stop – the end of the cave. We looked over the edge of the cave floor and peered down at the shiny railway tracks about 20-30 feet below. We were in the roof of the railway tunnel! It went no further.

Mystified, the floor seemed to have been worked almost level. We investigated the walls of the cave and found marks made by chisels, and then the remains of some old candles – no more than that. We were well rewarded for our curiosity, but our discovery only added to the puzzle of the Brandy Hole. Was this the cave entrance to the smugglers’ cavern; was it cut by early miners, or was it made by the railway engineers?

I returned once again some years later with my son Graham, and was lucky enough to take some pictures. Shortly after that, the railway authority eventually rediscovered the cave and its dangers, and shuttered it up. The images from inside (below) were kindly provide by Mr Beardmore an engineer with Iarnród Eireann.

After extensive inquiries with local historians, writers, the archives, local libraries, we were unable to find answers. We had ruled out the railway works, as there seemed no logical explanation for this large man-made cave in the side of the railway tunnel. The only explanations seemingly likely were; some undocumented mining or the origins of the Brandy Hole story.

The ruins of the nearby buildings precariously perched near the edge of a sea cliff on the outside of the tunnel in the image, has been equally difficult to explain. As there were constant falls of rock during the early years of the line, twenty-four hour staff were at one time employed at The Head to keep the tracks clear – this may have been a building where they slept on alternating shifts. The two small buildings appear on the later 1888 Ordnance Survey map but not on the earlier 1837 ones. Suggesting the buildings were erected at sometime between these years.

**Despite earlier attempts through the National Archives and their index to the archives of the Kilruddery Estate, access to view any material could not be secured. This was rectified quite recently when Lord Meath and his charming wife Xenia, invited me to view the archives. Explaining, that my requests and recent email had ‘fallen between two stools’, so to speak. The visit was delightful but yielded little, but was nevertheless not a blank. No explanation of the unknown building, recollection of any mining, nor any knowledge of the cave could be found. There was a map which clearly showed the Brandy Hole in the position alongside the now Brandy Hole tunnel and not where the OS shows it. It was dated 1810.

Perhaps the answer to the mystery of the Brandy Hole and the ‘piratical marauders tween Bray & Wicklow’ lies with buried with Murray at Newcastle.

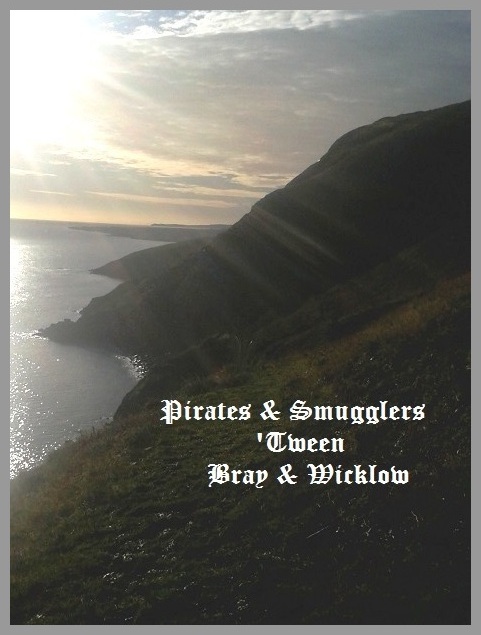

Featured image is of Bray Head. Brandy Hole in foreground – Cable Rock, Windgates, – Kilcoole and Wicklow Head.

* Further research may be possible and this article will be updated.

References.

Archives at Kilduddery House, Lord & Lady Xenia Meath.

National Archives, Dublin & Revenue files.

Freeman’ Journal, Saunders Newsletter & various.

History Ireland 1999.

Book of Bray by J.Sullivan, T.Dunne & S. O’Connor.

Book of Greystones by Derek & Gary Paine.