Local Wexford people know it as the, ‘Graveyard of a Thousand Ships’. There are that many lost ships there, and probably some more. The primary reason for such a large amount of unfortunate losses is quite simple – traffic. This part of Ireland represents a major crossroads for shipping, of increased importance, and more fatal at different times in history; such as, the mass emigration in the 19th century, and time of war.

The area is bounded by the Saltee Islands, Tuskar Rock, Kilmore Quay, and Carnsore. It was a mariner’s nightmare to be caught on a lee shore within the necklace of hidden rocks and reefs that are threaded between these sentinels, when the wind was contrary, or when the watch had not been able see the lights amidst the darkness all around.

It’s Never, Just a Name

It takes some imagination to crack the reasons behind the names given to some boats. Our own two are called, ‘Fourpence’ and ‘Ouzel’. I mean, how is anyone other than the owners ever going to work out the reasons for such names? They do wonder though. Not they are obvious, but the ideas at the time were interesting. The lure of an idea or the name of one’s favourite anything, becoming immortalised, by way of naming their boat so, is perhaps irresistible to some. Something like writing that book people say, everyone has in them.

The names given to ships and boats fall into almost endless categories, some more obvious than others. Warships usually have powerful or strong meaning names. Pleasure liners ‘….of the Seas’, have their own style. Then there are those after monarchs, admirals of yore, and famous battles. Sailing ships, commercial and private, were likened to be compared with others with a pedigree for swiftness, and so on. As these types of vessels are no longer being built, instead, today’s craft are bestowed with names that seem almost flippant, by comparison. Rubber Duck, Two Friends, Golden Monkey, Blonde, and Knot 2 Sirius. Nevertheless, there remains this thing in a boat owner, it’s his opportunity to make a public statement about himself, exploits, or his good luck maybe – ‘Lotto’, ‘Freedom’, his chance of adventure – Great Escape.

Forever popular, is to name your boat after a loved one, a wife, child, father etc. The ‘…Brothers…’ being universally popular. My own first boat named, Ann, after my wife, hoping that a selfish appeal to vanity might lower the temperature, when the dent in the family budget was discovered.

Some owners have even picked pop stars. Not a pop star, but Popes too have had their names painted on bows. Similarly, biblical names, children’s names like, Elvis, and other stars of stage and screen, and even more recently, football. Those of princes, emperors, and great warriors, were also popular names given to ships down through the ages.

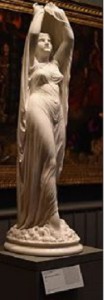

Interesting, was how former-day ship owners, mostly commercial, chose the Greek deities to revere, they were prolific. The reasons for such popularity, is not obvious, but may have originated in classical aspects of their education. Mythical goddesses of ‘plenty’ were favourites. Maybe they were just superstitious?

There is one name that gives no clue whatsoever, to its meaning. Instead, it is firmly announcing that there is something secret about the ship or its owners. People will always wonder, and even enquire. It is a name that only became semi-popular from the middle of the 19th century, but it has remained a registered name from time to time, especially in the warm seas of ‘tax havens’. It is, ‘The Secret’.

My friend, a rock of sense in such matters, advises; money has a tendency to gravitate to where it’s best looked after. Undoubtedly, he has clarity in this perception, but I doubt that ‘public money’ is as well looked after, especially when its ‘private’ brother is under threat.

The London to Dublin Route

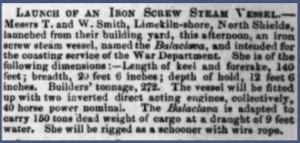

The Ceres was owned by the Waterford family, shipping magnates, Malcomson. Quakers, they maintained significant shipping interests in many port cities across England and Ireland, as did a number of other Quaker families. The iron screw steamer, schooner rigged with three masts, was launched at the yard of Smith and Rogers, Govan, on the Clyde in 1852, and was taken in command, by Captain Duddliston. She entered onto the London to Dublin route, and remained in that service until her loss.

Initially, and for a short time only, Ceres also sailed from London to Holland. These routes, often described by their destination and home ports, in this case, ‘London to Dublin’, they also served many other ports on route, depending on the commercial demand for freight and passengers. The Ceres made trips to her ‘home’ port, Waterford, on several occasions. One involved the delivery of the organ for the cathedral, and another involved the delivery of a ‘handsome new threshing machine’ – which seemed like ‘bringing coals to Newcastle’.

In the case of the Ceres and Ondine, both similar steamers, Malcomson had secured a government contract for the transportation of troops around Britain and Ireland. The contract was not exclusive to the military, and the ships also carried freight, passengers, and mails. With the comfortable backstop retainer of a government guarantee, this was a very lucrative arrangement, something Malcomson could go to the bank with.

Exactly how this arrangement worked is not totally clear. When owners had ships built, it didn’t mean that members of the family rushed to the tiller and sailed it back and forth. No, they let them out to agents. They in turn hired other agents, freight agents, travel agents, and so on, and it’s no different today. In the case of the Ondine, it was chartered to the shipping agent, Messrs. Robinson of Mark’s Lane, London, probably for a flat fee. There could have been cream on top, by way of freight or civilian passengers. Neither ship appeared in the Lloyds Registers, which was not a compulsory requirement at the time.

Arrangements that were put in place for insurance, would seem to have been adequate while the ship was on government business – carrying troops and mail. While carrying private and commercial freight, the issue became unclear, after claims were later pursued through the courts, for the loss of possessions and cargo by passengers and commercial litigants, when both ships were lost.

Ceres, quite a popular name for ships and yachts, was a female mythical God of agriculture. Representing I suppose, the earthy discipline of their model farms, dear to Quakers, and one which they excelled at. The Malcomsons’ home of Waterford, and the neighbouring county of Wexford, became famous for the production and innovation of iron farm implements and machinery. Although the Quakers were seen to present an ideal way of life, with outward appearances of being based on a Socialist model, known to have been extremely kind to victims of shipwreck and so on. They were also astute business people, showing no signs of meekness in the cut and thrust of the market-place.

Hardly seen at all on ships, Ondine or the alternative Undine (Malcomson owned an earlier paddle steamer named Undine.), is also classical, and was a mythical nymph, a servant to the Greek Gods. Ondine is also the name given to a modern sleeping disorder, associated with infants; sudden death syndrome, or ‘cot death’. Apparently named after the mythological permanent sleeping curse put on her lover by Ondine, for being unfaithful. There must have been something else in the minds of the Malcomsons though, as I can’t imagine naming a ship with anything that might represent – being asleep!

The themes in the family’s choice of names, of the known one hundred and twenty five ships, the Malcomsons either owned or had interests in, which Bill White lists in his invaluable record of Waterford shipbuilding history, ‘Shipbuilding Waterford 1820-1882’, are clear. Person’s names, place names in Ireland, classical figures etc.

With the exception, maybe, of the South American countries, there is little to indicate from the list, favouring any side during the American Civil War, even though the family business relied heavily on the shipment of cotton. It was the downturn and failure of this trade, which contributed significantly to the deterioration of the family’s fortunes.

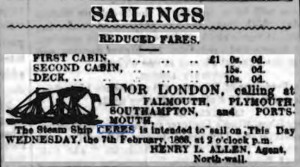

Ondine’s career was brief. Launched as a 500 tons vessel at the same time as Ceres, the bold advertisement boasted new fare paying voyages on the magnificent new screw steamer, 700 tons!, Ondine, London to Dublin, from first class at a £1, and 10s for on the deck. I could easily be wrong, but I presume a deck passenger was not expected to remain topside in the weather, for almost two days of sea travel around England and Ireland! Multiple ways of expressing the size of a vessel, ‘tons’, adverts always printed the big numbers. In Admiralty circles though, the Ondine was described as ‘a handsome little steamer’, later described as 380, and 309 tons.

The iron screw Ondine was launched in 1852, and sunk in 1860, a relatively short, but busy career. In that time, she had been involved in quite a number of incidents, strandings, drowning, collisions, salvage, and saving lives from wreck.

In 1859, the Ondine ran down the schooner Robert Garden in the English Channel. Her commander, captain Hunt, was subsequently found guilty of manslaughter for causing a number of deaths. Hunt was not committed, but freed on bail.

While still on bail, just a few months later, captain Hunt and the Ondine collided with the schooner, Heroine, off Beachy Head, in 1860. Only on this occasion, the Ondine went down, with significant fatalities. Captain Hunt and 106 other passengers and crew were drowned, and only two survived.

Reports of dead and injured always varied in such incidences, and this event was no exception. Twenty one were reported to have been landed at Dover, and nine of the Ondine’s crew were later reported to have landed at the North Wall, Dublin. The majority of the passengers lost, were military. Whether or not poor old Captain Hunt had been under the spell of Ondine’s sleeping curse, we’ll never know, as the subsequent Board of Trade Inquiry into the loss was abandoned.

Ships Get Lost

Events were moving rapidly in ship development. No sooner was the steam engine put into a wooden ship, they were replaced with iron ones. The screw developed and the paddles got the heave. Strongly built, these mid-century iron screw steamers endured for a long time. With the exception of damage or loss, certainly eight and fourteen years would have been considered a short life for such steamers. Another five years is all Malcomson’s Ceres got before she was lost.

Geographically, Carnsore is quite an exceptional extremity, situates as it is on the very southeastern tip of Ireland. Malin Head on the north coast of Ireland, The Fastnet, and Carnsore on the south coast, have all existed as ‘must be seen’ waypoints for deep sea mariners for centuries. Malin Head on the coast of Donegal, and The Fastnet, off Cork, mark the approaches for transatlantic shipping to the north and south of Ireland, and the British Isles. If Malin is missed, there could be no temptation to adjust southward until land was sighted. A cautious easterly course can still be steered until the high land along the coast of northern is eventually sighted.

Off the South of Ireland, it is pretty much the same with the Fastnet. If missed at the expected time, there can be no temptation to turn northward. A course eastward can still be steered, gradually merging landward, until high ground is seen. The crucial and dramatic course correction occurs, when Carnsore is reached. Unfortunately however, there is no high ground on that part of the coast that can easily be recognised, so there is a great reliance on that large rock, situated a few miles off Carnsore, called The Tuskar. It is here, a ship must alter its course northward, in order to sail up the Irish Channel and the industrial heartlands of Britain and Ireland. And visa versa going westward. It is no surprise then, that the want of a suitable light on the Tuskar was in contention for years.

There was no radio. There was no GPS, all a mariner had, although rarely used while just coasting, was a sextant, and a compass that could be used in conjunction with a calculation called, ‘dead reckoning’. A sextant was useless if there was no visibility, and dead reckoning was useless without an accurate compass. Sight was a very reliable aid. On a good day, you could see where you were going. At night you might be helped with the moon or the stars. In fog you were blind. Reduced speed with soundings was always recommended in such poor conditions. Night time, with snow, was probably worse than any other combination of gremlins. Not only was there no hope of seeing anything pass the ship’s rail, no one wanted to go on deck in the freezing weather, to swing the lead, or anything else.

Carnsore acts as a multi waypoint. It was, and still is, a guide for transatlantic traffic, but also for the traffic that came up the George’s Channel from further south, and from Pembroke and the Bristol Channel. In layman’s terms, ships rounded or passed Lands End, pointed up northward, and steamed away. On the right was Wales and on the left was Carnsore Point, Conninbeg, and the Tuskar Rock. With fair weather, the long out-jutting of Wales would be sighted in the NE, and after that, it was plains sailing for Liverpool, Dublin, or The Clyde.

Visibility and the wind were the flies in the ointment. Coming from the wings, east or west, could cause problems. Darkness speaks for itself. And if you notice in the advertisement for the journey from ‘London to Dublin’, always advertised at the rare best, of 18 hours, it would involve a leg of it during the night.

The predominant direction of the wind for most of the year, was from the west, which meant a navigator had to allow for drift sideways, to the east. But there’s always, that long Pembrokeshire coast and the broad expanse of Cardiff Bay, providing lots of space and time. Wind from the east, usually winter time, was problematic. Apart from being debilitatingly cold, a navigator had to allow for drift to the west, possibly missing the channel altogether, but there’s always the south coast of Ireland. So you see, visibility was everything, but there was no good seeing it too late.

In blind conditions, the compass is the navigator’s only means of directional steering. His original heading will become useless if there has been excessive drift, without having correctly compensated – but you don’t know this; how to calculate and adjust correctly, if you can’t see anything ahead of the ship? A stab in the dark!

Compensation and compasses. A compass had to be regularly checked by a professional mariner for deviation. That is, how much it has erred from its correct indication, north, south, and so on. To make magnetic corrections, the large iron balls on each side of the compass housing were moved in or out, until it read correctly.

The difficult person in the wood pile, was the cargo. Correctly ‘swung’, the compass or compasses, often more than one, could be relied on. That is, until you piled a couple of hundred ton of iron into the hold of the ship.

I would chance one of my few remaining inedible hats in a gamble that, at every inquiry into a collision or the loss of a ship, the captain or crew claimed that the compass was reading incorrectly. The beauty of this argument, true or not, is that it was impossible to prove the crew member was not being honest. The ship was gone, the compass was at the bottom of the sea, or quite simply, the conditions that ultimately prevailed were not as they were.

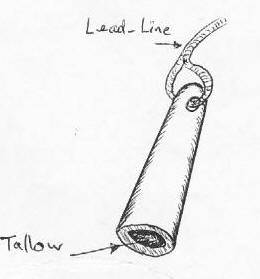

There is however another useful method of determining a ship’s position, or more correctly a position she is not supposed to be in. We look at a screen and, bingo! It tells you depth, type of seabed, position of rocks, temperature, what’s left out isn’t worth mentioning. The only method of telling the depth of water before electronic wizardry, was a method called taking soundings, or ‘swinging the lead’.

It meant lowering a lead weight with a hollowed-out bottom, attached to a string. When it hit the bottom, you stopped paying out the line, and measured it. When the lead was retrieved, the tallow that was stuffed in the hollowed out portion in the bottom of the lead, contained evidence of the type of seabed that got stuck in it, and ‘Bob’s your Uncle’. It is 20 fathoms deep, with some sand or shael on the bottom – but where’s that?

When used in conjunction with a ship’s log, a speedometer in a land lubber’s term, a calculation of distance run, by time and direction, can be a surprisingly accurate method of calculating the position of a ship.

The Royal Navy had been ahead of the game for years, surveying, taking seabed samples, and mapping the seas around the globe. The Western Approaches were very well surveyed, and every sailor worth his salt, new that there was a 50 fathom channel running up the George’s Channel into the Irish Sea. If you weren’t getting 50, and the depth was continuing to fall, you would soon be having a view of one coast or another from an unexpected direction, and had better alter your course.

That was the notional science of it anyway. In reality, it was not a bit like in the movies; a bare chested Errol Flynn leaning over the side of a sailing ship, under full sail, swinging the lead into the sea. Sailors just didn’t like doing it, for one reason or another. Bad weather was one, the continuous swinging, dropping in and retrieving the lead, shouting out the measurements, required effort and some experience, as there was knack in it. You had to be able to feel the bottom. In a steamer, you also had to keep it out of the propeller. Only experience would sharpen your ability.

For a reading to be accurate, ideally, the ship should be hove to – not being sailed or driven. If moving along at any speed, the lead and line would just tow behind, not touching the bottom. Compensating, by throwing it ahead, did not work when a steamer was ploughing along at ten knots.

Then there was the captain, he didn’t like it either. Time was everything, freight, passengers and mails must reach their destination promptly. Faster and better ships were rolling out of yards like the Clyde, daily. Railways and travel times were improving, and competition was fierce. Delays risked customers’ confidence in delivery times, and this was reflected in a captain’s bonus.

Ships Arrived and Ships Spoken

If Larry had been born, Pascoe might have been as happy as the undefeated pugilist. Not his first trip, captain Pascoe was looking up the channel in the direction of Dublin, on the last leg of his journey from London. And so it was, Captain William Pascoe, a name not as uncommon as you might think, who had replaced captain Fudge the previous January, was peering into his unknown.

Captain Fudge as it happens, had given evidence in support of another Malcomson skipper, Silly, when he lost their steamer, SS Adonis, off Bray Head in 1862. The Adonis had struck the Muglins rocks off Dalkey, just outside Dublin, and sank soon after. The crew and passengers got off safely, and came ashore in the ship’s boats at Killliney, and Bray. One of the boats had pursued the drifting and sinking steamer, until she went out of site off Bray Head. Despite repetitive searches, she was never found. Divers relocated the wreck of the lost steamer on the Codling Bank East Ridge, also called the Cobble Bank, in 2015.

The Ceres left London on November 6, 1866, stopped at Portsmouth, Plymouth, and then Falmouth. Carrying a general cargo, civilian and military passengers, with no sails up, she steamed out of Falmouth around midnight on the 10th, and rounded Land’s End at 3 o’c in the morning.

The captain managed the Ceres round the Longships and Wolf Rock lighthouse at Land’s End. The weather was ‘fine’ and the wind was not strong from the SSE to SSW. He chose a new course, NNE, for Dublin, and gave orders to keep steam well up until daybreak. Their next waypoint would be the The Smalls off Wales, on their starboard quarter at about 3 or 4 o’clock, during the following afternoon.

Sails were all set after Land’s End was put astern, but were reefed back again, when the weather began to get up at about noon. The course was adjusted a tad to, NExN, to compensate for the increasing wind and the tide that would fall out of the George’s and Bristol Channel. The log had been set and launched, measuring speed and distance. A good nine to ten knots was maintained. (This equipment was another aid to navigation. With a direction from your compass, intermittently logged readings of speed and distance from your log, a position could be determined. The log was not put out and retrieved repetitively as often as sounding the lead. And you hadn’t got to hit the bottom with it!) A relatively cheap piece of electronics today can display all that and more, on a screen, and tell you what time you can expect to be sitting down in the yacht club.

Just before 6 o’clock that evening, after the weather had deteriorated to a gale, with heavy rain, sails double reefed, and the log retrieved, the penny finally dropped. They should have seen the light on The Smalls. Equally upsetting, they might also have expected to see the Tuskar Rock lighthouse or Coningbeg.

Just briefly, all they got sight of, was the white water of the breakers dead ahead. The speed had only just been reduced, before Carnsore Point jumped out at them. They were twenty miles west of their presumed safe course.

It was later reported that Ceres had run on to some submerged rocks, and followed by an instinctive reaction, an emergency ‘helm to port’ was performed.

Again it was the darkness, they couldn’t see anything, and at first, believing that they were aground on some isolated rock offshore, the captain gave the order for ‘full steam ahead’, in the the hope of getting her off. The movement of the ship was short, pushing her a little further up the beach! This was also claimed to have been the intention. She came to a stop broadside to the shore and broke her back.

The captain, and what remained of the crew, were still unsure of the lie of the ship, and fired off the blue lights, only to see them fall and light up on the beach beside them. The stern of the ship fell over into so slightly deeper water, causing most of the fatalities. When the tide receded, the survivors were able to drop down the sides of the vessel and walk ashore. Making the loss of forty passengers and crew all the more unbelievable.

Wreck At Carnsore

The customary reports filled the columns. Trouble with boats, for which there was no need, the rescue of children, those who did not help for one reason or another, and those who behaved admirably. The Heard family were travelling to Dublin, and after the Ceres wrecked, Dr Heard returned to the wreck a number of times to rescue passengers. Along with crew, he saved his own wife and child, and his father, who was the Chief Coastguard of Ireland. Their servant girl,Bessie Gogarty, was drowned.

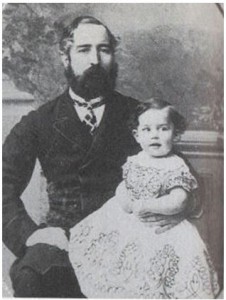

Dr Robert Heard and his son who survived the wrecks of the Ceres. (Courtesy of ‘Coastguard of Yesteryear’ and Helen Skrine.)

The area is still remote today, and one can easily imagine how more so then. Mrs Heard had to walk three miles over rough ground through the dark, before she found a door of a small cottage to knock on, and announce the tragedy. The local landlord, Major Keane, of nearby Castletown House, mustered some of the neighbours, and returned to the sight of the tragedy. They worked tirelessly through the night, recovering the dead and injured.

After the inquest was held in a nearby farmhouse, the bodies were interred in several graveyards close by, and some were transported back to their homeland. Some burials took place at the ruin of the 5th century chapel of St Vauk’s (Vaugh’s), situated on the Point. A place of great interest, archaeologists excavated there in the 1950’s, and amongst their finds, were remains of knights and of sailors. They are also reputed to have found bones from what must have been a ‘giant’ of a man.

Those who dwell around the remote coastline of Ireland have been all too familiar with loss at sea, particularly those on the coast of Wexford. This county, with a coastline to the east and one to the south of Ireland, has received thousands of bodies of shipwreck travellers. The Ceres tragedy was not a hugely significant one, but somehow, it’s darkness and that of the night, came across in the reports. The description of the bodies was harrowing, and because of its impact, I have decided to include the following extract in its entirety. I have read many such accounts, but this one has a simple naked honesty to its sadness.

Irish Times, November 14, 1866.

A fearful sight was that seen on the sands at Carnsore, on Monday, just as the evening was closing in. The people had drawn the bodies of the wreck of the Ceres high up on the beach, and beyond the spray of the breakers. The waves hissed along the shingle or moaned a funeral dirge beyond. They laid them in four rows – seamen, soldiers, gentlemen in the first and second rows, each line counting eleven dead. Then, beyond these ladies and serving women, just as they had been surprised by death, save that the seaweed strayed fantastically amidst their hair; and, lastly, beyond these again, three little girls who had been asleep when the waters came upon them, and never woke on earth. There have been wrecks on that same coast involving an even greater loss of life, but from few have so many dead been gathered from the sea so soon. There they lay to be hurriedly regarded by the coroner and the jury as they were drawn from the sea, awaiting burial.

The inquest had been held without delay, and found that the fatalities were caused by the wrecking of the ship, while captain William Pascoe was in charge. Pascoe could not explain why the ship was so far off its course. The inquiry by the Board of Trade followed soon after. Captain Harris, an old hand at unearthing the facts in these cases, went straight to the heart of the matter. Pascoe would have seen it coming, knew it was inevitable.

Harris reconfirmed the evidence Pascoe and others had already given to the coroner; that the lead was not used to determine the depth to the seabed, and that the compass had not been swung (calibrated) for over a year. Poor old Pascoe, a man with an excellent sea record, still couldn’t explain crashing into the southeast corner of Ireland, and had his ticket suspended for two years. In the scheme of things, a severe reprimand – always subject to appeal, though.

The Ondine and the Ceres were not registered at Lloyds, and the ships did not have to comply with the totality of their construction regulations, but they were compelled to comply with Board of Trade regulations, and the Merchant Shipping Act. But an interesting issue, one that had arisen earlier with the loss of the Ondine, arose once again.

In the case of the Onidine, owners, Malcomsons, refused to accept the Board of Trade’s verdict; that captain Hunt, the ship’s commander, was responsible for its loss. Not only that, but if Captain Hunt was deemed to have been responsible for the loss of the ship, then this had nothing to do with them! This meant that, those claiming recompense, by way of the owners, or insurance, had to prove their case in civil proceedings – which they did.

The loss of the Ceres presented the same issues, and Malcomsons presented the same defence – once again, an interesting position for them to have taken. They contended weakly, that the ship’s manifest had not been signed off on, that was one leg. The other was that, the Board of Trade was responsible for certifying Captain Pascoe, and although Malcomsons happily employed him, they had nothing to do with the certification process – they had not given him his ticket of competency. And perhaps, if the BOT later found him negligent, then maybe they should compensate the claimants? Sounded like a runner, but the Malcomsons lost once again, but maybe it had more to do with the fact that they were also deeply involved with the insurance industry.

Wreckers, Smugglers, Criminals, or Lifesavers?

There was no doubt in this case. No attempts had been made to lure the ship onto the shore. No straying lights on hilltops, no roaming animals with lights on their horns and there wasn’t a smuggler in sight. The ship ran up on the shore, bodies and cargo spilled into the surf, and onto the shore, and local people stole things that did not belong to them. They had done it for centuries, and they still do it. The accused were identified, searches were conducted, and the culprits were brought to court, where they were fined mostly for stealing.

The amounts were small, and reflected a general attitude to these kind of ‘wreckers’, which they weren’t. This was not always the case everywhere, and some very stiff penalties were handed down before this instance, and for later ones. In the case of mariners and their vessels in distress, the overwhelming action taken by local people around the coast of Ireland, has been for the care for life.

As it was put in 1799, during a particular disastrous loss of life and ships in Dublin Bay;

‘A few of their unhappy crews have got on shore, with life, though in a torpid state, but from the humanity that has been exercised towards them, they are expected to recover. Amongst the many vessels forced on shore by the late gale, one, supposed to be bound to the West Indies from Scotland, was boarded by the Keary (The name of Ireland’s present day and foremost survey vessel.), pilot wherry, of Clontarf, at the risk of the mens’ lives, who found that every one of the crew had perished by the intense cold of the night – and with that humanity that always characterised the men of that quarter, they cut them out of the shrouds and brought them to Clontarf to be waked and buried.’

This was before any lifeboat organisation, these men and women, from all around the coast, instinctively rushed to save lives first. When the lifeboats did arrive, they were the first aboard. They were were on the shore, and in the sea, helping victims and sheltering them, before any landlord appeared. The crime was not one of stealing from the dead, picking up that which was lost at sea or washed ashore, it was instead, one of flouting authority. And where, one may ask, did the valuable shipwreck items from the Spanish Armada, 1588, end up, after their owners were slaughtered in the surf? They can still be seen in the big houses!

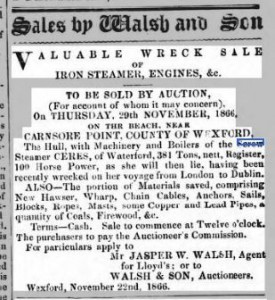

The Ceres was high on the beach, not totally up on the deckchairs, and was later put up for sale by the local auctioneer, Jasper Walsh, who seemed to have that part of Wexford pretty much to himself. It always surprises me, just how much early salvors and contractors, men of unique innovative determination, could achieve. This was a remote area, served only with the most basic tracks, and it is a credit to their ingenuity or maybe their desperation, that such wrecks could be completely dismantled in such an efficient manner in so short a time.

A surprising amount of iron cargo, tea, spirits etc., was saved and auctioned in the first instance, and the remainder dismantled and sold for scrap, so that little remains can be seen today. The iron bits or bollard around the Point of Carnsore, at Port Carnagh, Nethertown, is probably from the Ceres. A cargo of tobacco was not mentioned at this juncture, but would later become the subject of an interesting point of law, already mentioned.

The large iron barque, City of London, that run up on nearby Tacumshane beach, 10 years later, a mile or so further west, lodged in slightly deeper water, but was also stripped bare of almost every conceivable item of value. It is a very nice shallow dive with the whole hull of a ship to explore.

De Javu – HMS

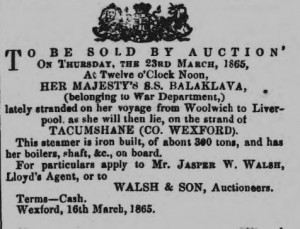

Whether captain Pascoe knew or not, but an almost replica incident had occurred less than a half a mile, further west on the beach, the previous year, on February 24, 1865. The British war department’s store ship, HMS Balaklava had run up on the beach at Rostoonstown, and was never able to get off again. (I have used ‘HMS’, as did reports. Described thus, and almost as everything else, she was not listed as a Royal naval loss. Leading one to believe, that she may have been a government hired vessel.) Another iron screw steamer built at Smiths, she was also travelling the same route from the south of England to Liverpool, with seventeen Armstrong guns and carriages, to be fitted into Royal Naval ships being constructed there. Just as in the case of the Ceres, insufficient attention was observed to their actual course and position, and she too just ran into the beach at Carnsore.

The American Civil war would officially come to an end in just a couple of months. In reality it was already at an end, the South were defeated more than a year previously, when Britain finally decided that they could no longer sustain the old ‘Nelson’s Eye’ approach to the support and arming of the Confederates by British marine and armaments industries. For whatever reasons, ignoring the issues hadn’t worked, and had allowed public opinion a rampant vent of support that manifested in the, ‘Siege of Liverpool’, where it was said more Confederate than British flags flew.

The Armstrong guns were in direct competition with Blakely ones, which the department of war refused to purchase. Blakley, accusing the British military of stealing his designs, had his armaments produced under licence at a variety of UK engineering works, and amongst other customers, sold them to the Confederates. The large Blakely guns, muzzle loaders, were considered to have better armour piercing qualities than the British Armstrong. The argument went back and forth, but the RN returned to muzzle-loaders.

In command of the Balaklava, Captain Pellat, and his crew, may not have been able to see where they were going, when they ploughed into the Norse headland, but they, and a detachment of Royal Marines under the command of Captain Smith, from the Prince Consort, sent to salvage the wreck, acquitted themselves admirably.

Aided during the operation by the family at nearby ‘Doyle’s farm’, some of Balaklava’s crew and the marines, camped for a number of weeks in the dunes at Rostoonstown, and accomplished a herculean task. Seventeen guns, some weighing in excess of thirteen tons, and a steam engine, were hauled out of the wreck, up through the sand dunes, and onto a nearby track. Just walking up those same dunes, makes your sinking feet feel like lead.

Bridges had to be improved and reinforced, while the guns were being carted across the county to Wexford town, before being shipped back to England. The job of managing the loading and transportation through Wexford county, was awarded to Pierce of Wexford, who was applauded for his efforts and his supreme engineering skills. The amount of beef and bread that was supplied to the company during the work put a few more on the ‘pigs’ backs’.

Not a full Board of Trade enquiry, but seemingly an enquiry more suited to the loss of this particular vessel, apparently not a Royal naval ship, was held in April. A collection of qualified men, from civil and royal naval pedigree were selected for the panel, Captain Harris once more in the vanguard. The result, avoiding the words ‘guilty’, ‘Royal Navy’ ‘Captain’ or ‘your fired’, was summarised to the Press; ‘…the late master-in-command of the War Department steam store vessel Balaclava…was sentenced to be superseded from his duties and to be mulcted of all pay and emoluments for the ensuing three months’. Effectively, Pellat was considered of retiring age, and got the heave. Described as a ship’s master, he was not mentioned in the years that immediately followed, and it is not clear if he remained at sea.

Lane of Stones

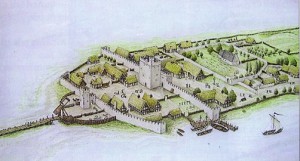

Where the Ceres wrecked, was first described being at the, ‘Lane of Stones’. Later reports varied slightly in distance, westerly from Carnsore Point, county Wexford. The most westerly position reached an area, where the lough, Lady’s Island, meets the sea. A lake now, but shown on old maps as being totally open to the sea. Still partly open in 1840, it remains closed now, until flooding threatens, and then a ‘cut’ is made in the dunes, to release the flood waters. The estuary once provided a haven for fishing boats, and an ideal landing place and shelter for the Norse people and their ships, when they arrived in the area. (An interpretive depiction of Lady’s Island by Wexford Co.Co. shows the typical double ended Viking design boat berthed up the lough, alongside the castle on Lady Island.)

The Normans settled the area, and left their mark in the attachment of ‘ore’ to the local names of Carn and Green. Leaving much more than names, they improved politics, land management, navigational skills, military skills, and even skills in the arts.

The area from The Tuskar to The Hook is steeped with so much history that is still visible on the land, and in the remains of written works. Having a reputation for so much sunlight, the place, is said to have attracted the mythical race, Tuatha Dé Danann, and then the Celts. Druids, Monks and Monasteries all followed, as did the Norse people, Knights, and of course Cromwell also had a go at the area too. So much to discover, the area has become a significant draw for walkers and holidaymakers following ‘The Norman way’.

A somewhat detailed location of the wreck of the Ceres was given in the Irish Times, describing the site as, ‘..under the Hill of Chour, one and a half miles west of Carnsore Point’. Chour Hill, or Giant’s Hill, stands a little more northerly over the dunes and into the land, and it is the only piece of high ground in the area. Believed to have been eroded somewhat, it really is only a pimple on the landscape, but nevertheless, catches the eye amidst the surrounding otherwise flat countryside. It may once have had a fort or light on it, marking the entrance to the brackish lough, called Lady’s Island.

An explanation for, ‘Lane of Stones’, the name given to the lane, which comes from the direction of the hill, towards Carnsore Point, a place where there was an ancient tomb, seems to have been lost. Local people just refer to to it as, a lane of stones. Grappling with the explanation; when the fields in the area were being cleared of stones for planting, they piled them all to one side. And just like in many other places around Ireland, the people erected miles of dry stone walls to delineate the separately owned fields, and to give some protection from the harsh weather.

However, to me it just doesn’t gel. Certainly there is a multitude of stones, millions of them, and the fields are still being cleared of them. Was the lane built of the stones, or was it used to draw stones? The important point here is that, it was a lane – indicating that it was used travel to the seashore. Were carts bringing something to the shore, or away from it? Having a stone road capable of supporting a cart travelling to and from the seashore was of considerable benefit, for a number of reasons. Shipwreck, and items recovered from them, life saving, seaweed, and the movement of food, fish etc. Seaweed was used extensively in the area in the cultivation of the fields. There are numerous incidences of vessels lost while transporting ‘wrack’ – seaweed. The red granite in the area is particularly eye catching.

There is more than one lane filled with stones in the area, and present day land owners are still filling them with stones to keep them passable for their vehicles.

As with many of ancient places in Ireland, the meaning of their names has been lost, and are continually undergoing re interpretation. Carnsore is a derivative of Carn, a ‘monumental mound of stones’, also meaning, and probably closely associated with, an ancient type of burial tomb. Carnsore, supposedly had a few of its own, ‘The Giant’s Grave’, situated right on the edge of the Point, but its remnants are scattered now, and any constructed one resembling an original, now hard to find. (Giants get considerable mention in this Bay of Shipwrecks.)

On the east side of the Point, Nethertown, is an area known as, Carnagh Port. Cleverly situated, and seemingly an ancient landing place, that was reconstituted somewhat during Famine relief work, remains of an old pier and harbour are still visible there. At the back of this once small harbour, there are iron securing rings in the rocks. In the sand, used for hauling up boats, an iron bollard from a large ship, most likely brought around from the wreck of the Ceres.

The next promontory, Cross Fintan Point, a little further eastward, between Carnsore and Carne harbour, also has evidence of an ancient road or landing place at the seashore, which seems to have been largely overlooked. This particular road of stones appears to come out from under the embankment, and leads to the sea. But then the sea wasn’t always there. There is a lot of evidence to suggest that this headland reached further out to sea, and in the sandy bay into which the stone road leads, there was once a forest and a bog. Evidence of bog and tree stumps can be seen from time to time, during periods of large movement of sand.

The small townland of Carne, with a nice little pier harbour, and the famous ‘Lobster Pot’ restaurant, is situated a half mile further east, just around the corner. The whole of this area is very popular for holidaymakers, and is generally known as Carn.

The term, ‘Lane of Stones’, does not appear in a trawl of the British Newspaper Archives, beginning in 1700, until the occasion of the loss of the Ceres in 1866. (Many newspapers are not included in this archive.) There is much to see in this part of Ireland, and a lot of it, not fully explained. Peculiar to Ireland and this part of Wexford, Forth and Bargy, its inhabitants had their own Old English dialect, Yola. Said to have been introduced during the Norman invasion, the following is the third verse from a small song about three maidens at Chour Hill.

Zong o’Dhree Yola Mythens

Wu’ll go our wyes to Chour Hill

And tharr zit down and yux our vill

An eachy tear ud shule a mill:

Poor Yola myrhens.

Courtesy of WWW, ‘Alphalingua International’.

Almost impossible to just run into it now, Carnsore is planted with wind turbines. These are the new clean energy savers, but upset the calm of the place, with their deep bass whooshes. Being so close to the shore, one wonders how much money might be spent preventing them from going the way of the land beside them. Perhaps, more acceptable than the nuclear power plant that was once proposed to be built there?

PS. Richard Roche’s book, Tales of the Wexford Coast, mentions the wreck of the Sirius, reappearing at Carnsore, in 1932. This was reported in local newspapers, but appears to have been a mistake. A wreck did appear during unusually low tides, but was apparently that of the Ceres, and the incident was described by a living witness, as; ‘one of the saddest sea tragedies of the Wexford coast’.

Thanks to;

Wexford County Archives, Fr. Cogley of Our Lady’s Island, Google Earth, British Newspaper Library, ‘Shipbuilding in Waterford 1820-1882’ by Bill Irish, and the WWW.

PLEASE NOTE:- All images, text and video contained in this post, can not be reproduced without permission of the authors or accredited artists.