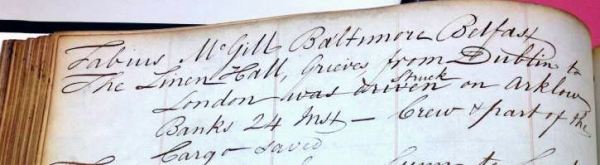

A Tale of Shipwreck and Lost Treasure

The Banks

Many will be aware, and unfortunately for some, they will also remember only too well, how Banks can ‘fail’. The term is of course not an honest assessment of events when due governance and propriety are recklessly abandoned in favour of greed. Terms like ‘maximising profit’ or ‘sweating the buck’ are bandied around, but instead, and lets ‘call a spade a spade’, a better description is ‘fraud’. Not incompetence mind you, as the principals always seem to manage to do quite well out of it in any event.

The phenomenon is not new of course, except nowadays, Banks tend to just throw their hands up, and with the connivance of malleable politicians, slip their Fagan like digits into Jo Taxpayer’s pocket for more money. It has to be done – the ‘State would fail’ otherwise!

This same old time-worn scenario was being played out in 1822, after a plethora of finance houses in Ireland, and less so in England, were ‘going under’. Promissory notes were being declined as a result of cash deficits – bad lending, and for reasons bankers couldn’t agree on, cash was becoming scarce. A number of measures were executed; reducing the return on government stocks, and the old reliable, the Navy Fund got a haircut. An organisation that always made good on its borrowings, but sometimes a little late, and sometimes at an altered rate of interest – downwards.

The Bank of Ireland (BoI), only 38 years in existence, was experiencing a nice little run on their notes in exchange for gold. The BoI’s paper notes were considered a safe bet, so they became more valuable. The financial pecking order of value was; English money, Bank of Ireland money, and a surprising third – gold. The difference between the highest and lowest was three and a half per cent. It caused a run on notes and the BoI eventually had to desist from accepting coins. This led to a row and threatened the renewal of their charter, which proved to be just noise. The movement of gold and silver coins resumed.

Amongst the financial remedial measures taken were; consolidation of the old perennial ‘Sinking Fund’. An Irish Government’s modern equivalent, the ‘National Pension Reserve Fund’, was sucked dry to ‘save the country’ after banks threw their hands up once again in 2008. The latest fund sensitively re-branded, as the ‘Rainy Day Fund’. Banking or meteorologically speaking, I suspect the fund will suffer a similar fate at the same hands – and will eventually be sunk.

In 1822, the postal service, a method of communicating news, commercial transactions, and increasingly important, transferring money and credit to various and remote parts of the country, had been under attack from highwaymen. Their activity began to threaten the progress of commerce, with clients and banks suffering the loss of cash and ‘cheques in the post’. Consequently, the secretary of the General Post Office in Dublin, Edward Lees, was compelled to have a number post boys incarcerated who were suspected of being complicit in the hoists, and suggested that ‘notes should be cut in half and posted separately to avoid loss or fraud’. Which perhaps is where, the cry of the reluctant debtor, ‘your cheque is in the post’, originated.

At the same time, gold was been acquired by the Band of England (BoE) to bolster reserves. And after a recent high demand for BoI notes, that Bank had lots of it. In addition, gold coins that were considered worn or defaced were being taken out of circulation, as were small value copper coins, duds and tokens. It was an odd thing that even though some coins, copper and silver, were being taken out of circulation due to being debased from ware, the assistant secretary of the Bank of Ireland, Mr William Graves, was reporting that there was a shortage and that there was a need to import more. He also reported that because the value of the metal in low-value coins was of less value than the face value of the coin, counterfeiting was on the increase. It was on the increase and so was the BoI’s demand for them in order to melt them into ingots.

Not counterfeiting, but the collection of ‘clippings’ from all coins, the raw material for the same illegal activity, was rife. Causing havoc, the counterfeiting of notes was also prolific. Seemingly, counterfeiting notes in backroom printing houses did not present and significant problems.

The Financial Climate 1822

Banks had gone under before, and notwithstanding the high number in the recent past, no one could have foreseen that this was not cyclical, but the beginning of an end – and more ‘ends’ would follow. It would take twenty more years of financial drain, a transfer of wealth out of Ireland and record increases in population year on year, before a giant poverty trap sprung, subjugating millions of victims. It joined with a plague of Famine and decimated the population of Ireland, with other parts of the United Kingdom not faring much better. The population of Ireland at the time was said to have been 7.6 million and rose to almost 9 million at the height of the Famine. Numbers then plummeted by half during a decade, from death and emigration.

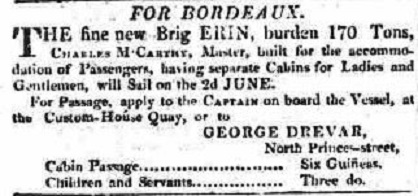

A strong demand for silver and gold existed in 1822, and a premium was being offered by the BoE for gold, coin or bullion. An opportunity not to be missed, George Drevar, a director of the BoI, was tasked by his fellow directors to ship their tidy collection of guineas (gold) from their bank to the BoE in London. The first shipment, said to have been one of a number to follow, and would total £100,000. (The equivalent purchasing value today is £12.6 million) Gold had been stubbornly set at a steady value of £3.75 per ounce, but could nevertheless achieve inflated prices at times. Such as during the Napoleonic Wars 1817-1821, when there was a run on gold. The BoE was offering some of its customers, £4 -1s stg. per oz.

The BoI had already profited on the exchange of its notes for gold, and the BoE was then offering it a premium for the gold. It was a hefty profit for doing nothing. They call it a ‘win-win’. Some might say, ‘you can’t lose’, and other less kind remarks. The number of Bills regulating Banking at this time had the printing presses in overdrive, and it remains a difficult period on which to get a handle on what exactly was going on. These are echoes of a financial service industry which reverberate to this day and probably quite intentionally so.

This first shipment was described by the Press in a variety of ways. ‘Guineas to the value of £25,000’ – ‘25,000 guineas’ – ‘Gold species’ – ‘Two chests of gold, 1 cwt each’. An isolated report in a Scottish newspaper described the cargo as ‘23,000 guineas’. Twenty-five thousand of the gold coin, guinea, was the most prevalent description. At the nominal price, £3.75 per oz., the gold per weight value of the shipment , described as ‘2 cwt’, amounted to £28,125 – roughly £3.5 million purchasing equivalent today, which is at odds with the alternative value quoted at the time – £25,000. There are no surviving BoI records that provide any confirmation on the details of this shipment. Surviving correspondence across the channel in the BoE [Note 1], does suggest such a transfer was expected, but it never arrived, so there was no record of it. A question arises – who was responsible for the shipment until it arrived at the BoE?

Note 1. [BoE records confirm that Arthur Guinness, governor of the Bank of Ireland, had written to the BoE in October 1821 seeking to establish an account – this was described as being; the Bank of England would become an agent for the Bank of Ireland. This was confirmed in the positive, and the Governor of the BoI noted that a shipment of gold would follow to commence business. It was also the time when the BoI acquired an exclusive licence for its banking operations within a 50 mile radius of Dublin]

To be continued…

A Shipment of ‘Confidence’ in the Linen Hall

George Drevar wore a number of hats, as merchant members of the Ouzel Galley are oft known to have. Present tense – as that 300 year old plus, delightful organisation, with restricted membership and strange rules, is still alive and well, if just a little media-shy. One of George’s other prominent pieces of headgear came with the position, ‘Active Agent for Lloyds Insurance Underwriters in Dublin’. It follows, therefore, that it was only logical to expect that George should be the man best left to look after anything to do with shipping matters for the BoI – despite or maybe because of the very unusual nature of this shipment.

The guineas (Minted entirely from gold, .30 ounces each.) were assembled in two iron chests and loaded into the schooner, Linen Hall, lying alongside Rogerson Quay in Dublin. Her captain, Joseph Graves (Sometimes spelt Greaves & Grieves.) supervised the loading himself and never left the ship again, until after she sailed. There was also a consignment of paper money and exchequer bills with the coins.

The chests were placed in the bottom of the ship and were covered over with a large number of sacks of flour and a reported, ‘150 packages of Linen’. Any additional cargo was not mentioned until later.

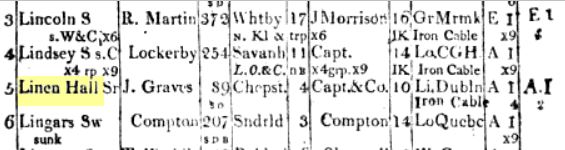

At 89 tons, the Linen Hall was a relatively average schooner and questions as to her suitability for conveying such valuable cargo would arise later. She was built in 1817 and reportedly owned by Parsons Hurles & Co., linen merchants of Bristol. Lloyds Register for 1822 indicates that the captain of the Linen Hall, Graves, was the owner. The ambiguity presented by this entry may only have been a result of convenient administration at the time of the ship’s inclusion in the registers and remained unaltered. Alternatively, Graves may have held the majority of the shares in the vessel.

The Linen Hall had returned from her previous voyage to London and berthed in the Liffey on March 1, 1822. After a number of days, George Drevar reported to his fellow BoI directors, including William Graves, who would become Secretary of the BoI, that their cargo of species and notes had been insured with Lloyds, loaded on board the Linen Hall as described, and would sail for London on the evening tide of Sunday, March 24, 1822.

A regular coaster, she was in tip-top A1 insurance class condition, matched by similar opinions of her captain, Joseph Graves. With a coppered bottom, her record for channel runs had been excellent. A fine profit could be had from a tight ship, run by a competent and reliable master and a smart crew.

To be continued…

A Treasure Ship out of Dublin

It was already dark when the popular schooner warped off the Liffey wall at Rogerson Quay, and with the wind westerly she took the flow of the river easily, sailing seaward against the dying flood of a rising tide, at about 10.00 pm. They reached the light at the entrance to the port, adjusted sails, turned to starboard and headed south. The tide was about to ebb and would carry them at a welcome extra couple of knots down the Irish Sea. Their southern horizon was not without some tell-tale guiding lights, twinkling along the coast and over the hills of Killiney and Bray.

The course ships, motor and sail alike, take to the south from this point, the Poolbeg Light, varies even today. According to weather and experience, a ship may proceed the extra five miles east to the north end of the Kish Bank [Note 2] or pass through the dangerously shallow Kish Banks at a place called, The Swash, situated between the Tail of the Kish and the beginning of the Bray Bank, which was about six miles further south. The safe navigable width of this Swash was dangerously narrow, and only the most competent mariners familiar with it, tended to use it. Heading south, the ship will remain outside of all the sandbanks that straddle the coast down the Irish Sea to the Tuskar Rock, County Wexford.

Alternatively, given weather and competency, a skipper can decide to take the shorter route inside the Banks, coming out to of these channels to the open sea at Wicklow or at the end of the Arklow Bank. The weather had to be right and a skipper had to ‘know his onions’, but the saving could be considerable, and the journey pleasant.

Both of these conditions were present when captain Graves gave orders to head south, keeping between Dalkey and the Kish Bank. The weather couldn’t have been better when they passed Bray Head, and Graves gave the order to the mate, Richard Bibby, to keep the ship on a southerly course until they reached the Wicklow Light, one of the few along the east coast, and then to call him. The wind was fresh from southwest to west and the smart schooner sailed close to the wind, beginning to increase its speed until it reached an impressive twelve and a half knots.

Captain Graves was called about midnight while the schooner was still inside the Banks. Sailing hard and close to the wind as they left Wicklow Head astern, happy with the ship’s progress, Graves went to his cabin at about 1 o’clock in the morning, leaving instructions with the first mate to waken him at 3 am.

It appears Captain Graves was still in his cabin when the schooner’s keel struck hard on the Arklow Bank and came to a stop, ‘nine miles from shore’. Descriptions of ships’ positions that are found in early reporting of shipwreck, often appear at first glance to be quite good ones, but when one attempts to work out an actual position, you come to realise that they often lack relativity – the actual position on the shore from where the measurement is meant to be made from. [Note 3]

From the reports that came later, it is hard to determine at exactly what time the incident occurred. Given that high water had occurred around 10 o’clock on the evening of Sunday the 24th in Dublin, the turn of the tide could be expected six hours later, but almost three hours earlier at Arklow. The schooner would have to be passing out through the Arklow Swash or the end of the Bank, a few miles further south, at about two o’clock in the morning – which appears to have been the case.

It was a windy night, blowing from the west with a bit of north beginning to creep into it, and not particularly bright. In March, the visibility would most probably have been very poor. It is possible the lighthouse on Wicklow Head was still visible, but there were no lightships on the Arklow Banks to guide them at this time. The crossing out was misjudged. The ship, drawing less than 3 metres, grounded on the Bank and fell over.

Note 2. [The first lightship was moored on the Kish Bank in 1811.]

Note 3. [The Arklow Bank is generally only 5-6 miles from the coast on either side of the entrance to Arklow harbour. There is no position on the Arklow Bank that is ‘nine miles from shore’ – directly.]

To be continued…

Beam over on the Arklow Bank

When an early 19th sailing ship fell over on her beam after grounding in such circumstances, it was almost impossible to save the ship. Some later salvage attempt, or righting of the ship at a different stage of tide might be possible, but a wooden ship lying on her beam had not long before the sea pounded her timbers and finished the job.

The Linen Hall immediately began to fill with water and the crew took to the high side of the ship that was just barely out of the water. Despite the difficulties trying to keep from the danger of being swamped and swept off an acutely sloping deck, the crew managed to disentangle and lower the small lifeboat into the water. They secured the little boat to the ship’s rail by its painter, and the captain and two crewmen, Thomas Abbot (The ship’s boy with the nickname, ‘Rabbit’.) and Joseph Smith, managed to get into it. The mate Bibby attempted to follow, but his leg got trapped between a water barrel and the side of the ship. The other crewmen, Patrick Holden and John Davis, lent a hand freeing the trapped Bibby but found the going difficult

The constant tugging and thrashing of the small boat against the hull of the schooner was too much for its painter, and it finally parted. The Captain and the two crewmen already in the boat were swept away immediately. Luckily, they had a pair of oars, but nothing else. The lifeboat blew before the wind at a terrific speed and was out of sight within a very short time. There was no possibility of rowing back to the wreck of the Linen Hall. The terrified sailors that were stranded on the stricken schooner were forced to take to the heights of the rigging and wait.

At this point, events proceed in two very different directions, with quite unexpected consequences. The fact that the lifeboat got away from the stranded schooner in this manner, before the remainder of the crew got in, was unusual, but not exceptional. [Note 4]

The fact that the captain got in before the remainder of the crew was irregular. And there did not seem to have been a good reason why an experienced crew and a well-found ship on a voyage that was familiar to the captain and crew, should have misjudged their position. Exactly where they attempted to cross the Arklow Swash or the Tail of the Bank is unknown, but some clues were revealed. Notwithstanding, it is also possible that she attempted to cross out at the Wicklow Swash, off the north end of the Arklow Bank, and there were some remarks in the reported testimony by the survivors that would indicate this.

Note 4. [Inadequate and poorly maintained lifesaving equipment, has been a recurring factor in shipwreck and fatalities through the history of seafaring.]

Rescue at Wicklow

The three surviving seamen, Bibby, Holden and Davis, climbed higher into the rigging in an attempt to keep sight of what had been their only hope of escape as it drifted it out of sight. The ship lurched further over to an even more extreme angle and they clambered up the last few feet to safety, as the protruding bulwarks began to sink below the level of the sea. A sure sign that the sand below her was beginning to scour and the ship was slowly sinking into it. The men began to frantically wave any materials they could, in an attempt to attract attention. Although a long way from shore, the Arklow Bank can be seen from the high road above Arklow on the north side and even more clearly from Arklow Hill (Roadstone Quarry) on the south side.

A number of boats set out from Arklow and approached the stricken vessel, including ‘two cutters’, which was an indication that the Preventative Water Guard men had observed the incident and along with some fishing boats, had put out to attempt a rescue.

The problem was, the Linen Hall was stuck up on a very shallow part of the Bank and the rescue boats could not venture near her at first – it was late Monday afternoon. When the wind abated somewhat, the fisherman owner, John Cavanagh (as reported) let out a long rope from his boat, upwind of the wreck, allowing it to drift down onto the survivors perched on the mast. One after another they jumped into the water, caught the rope and were dragged into the fishing boat. It was a bold and clever rescue which saved all three men.

The three crewmen rescued out of the Linen Hall by the fisherman John Cavanagh from Arklow were reported to have been conveyed to Wicklow, not Arklow. This might have been because of a more favourable wind for Wicklow, but might also indicate that the fishing boat could have been out of Wicklow and that the event had occurred nearer to Wicklow harbour. Penniless, and barely clothed, they were later conveyed by another fishing boat to Kingstown, and from there, they walked a further six miles to the offices of Parsons & Hurles on the quays in Dublin.

Whether it was confusion with subsequent events or not, it was reported that the three crewmen returned to Arklow and made an attempt to reach the wreck in order to save the cargo. This aspect of the story would prove controversial, as the crew’s action clearly indicated they had abandoned the wreck after the rescue. This could affect any subsequent claims by salvors – possibly even extending to their own attempts at ‘saving’ the cargo. Returning to the wreck might also have been an attempt to re-establish rights over their vessel and cargo.

Nevertheless, the crewmen landed at Kingstown [Note 5.], reached Dublin and were interviewed. They gave evidence to magistrates on Thursday, March 28, and it is at this point during events that details of their reported testimony presented some difficult to explain discrepancies.

Note 5. [The diminutive harbour of Dunleary had changed its name the previous year to, ‘Kingstown Harbour’, in honour of King George IV. The massive construction project, the Royal Harbour at Kingstown, had commenced in 1817 and would not be totally completed until the 1850s. Mostly reclaimed by town development and the railway, some small area of that earlier harbour remains and is called the Inner Harbour or Coal Harbour.]

To be continued…

What the Survivors Said

The first aspect of the sailors’ testimony that warrants scrutiny was the three crewmen’s statement that, 12 bags of flour and one pipe of wine was retrieved from the wreck of the Linen Hall. How did they know this? Had they seen someone landing on the wreck? Had they returned to the wreck before proceeding to Dublin, or was it just that they had heard this in Wicklow?

The pipe of wine, a tallish barrel of over thousand pints, is a puzzle, as it was not reported that the Linen Hall was carrying a consignment of wine. As this was almost like sending ‘Coals to Newcastle’, we must therefore assume, generous and all as it might seem, that the wine was from the ship’s own stores!

A further difficulty arises from the remarks made about the gold, which was reported to have remained in the two boxes and stored ‘beneath the floor of the ship’. This remark was so categorical that it suggested they knew the boxes were still there. The assumption that was drawn from either the statements by the crew, their examiner’s summaries or a compilation of reports by someone was, there was still hope of recovering the gold.

In this belief, they were supported by the additional knowledge that must have been relayed by others – that the wreck ‘was being strictly watched by the Coastguards’. What appears to have happened was that separate accounts of the incident were jumbled together for or by the Press, suggesting that the crew had seen some of the cargo being removed. But as we might understand it at this point, this could not have been the case, as boats could not get to the wreck at that earlier time. Despite this, it was reported on Friday, March 30, that an additional 10 packages of linen had been recovered from the wreck. It appears then that someone had reached the wreck and began to ‘save’ some of its cargo.

There was no telegraph, but there was a postal service, and there were small vessels continually trading up and down the coast, either of which could have relayed additional intelligence concerning the loss of the Linen Hall on the Arklow Bank to the offices of Parsons & Hurles. Even a man on a horse could make the journey in a day.

At Dublin

The news reached the offices of George Drevar & Son, who had a number of premises in Dublin, and a third strand to the incident unravelled. Undoubtedly the coastguards also notified the authorities in Dublin and Lloyd’s Agent, director of the BoI, George Drevar, who would have been one of the first men to be made aware of the casualty that had occurred ‘near Arklow’. [Note 6.] And almost certainly, Captain John Kelly, Lloyd’s appointed agent in Arklow would have done the same. Drevar had arranged and supervised the shipment of gold on the Linen Hall and had lost no time contacting Lloyd’s head-office in London to acquaint them with the circumstances of its loss when the details became known to him.

Note 6. [The Water Preventative Guard (Water Guard) and some Revenue staff where amalgamated that same year to form the Coastguard Service, but did not evolve into a single administrative entity until later. We will refer to the Revenue and the Water Guard people as the Coastguards for the purpose of simplicity.]

At Waterford

There was a belief that Captain Graves and the two crewmen had been lost, but unbeknownst to almost everyone, the small boat had been spotted about 40 miles from the Irish coast by Captain Charles Payton (Also spelt Peyton.) of the brig Catherine, en route from Belfast to London. The small boat and the three men were saved. They were conveyed to Dunmore East in the Waterford estuary on March 27/28, and from there the men travelled to reach Dublin on Saturday, March 30. Captain Graves was reported to have returned to Arklow immediately, in order to save some of the Linen Hall’s cargo. Whether it was Captain Graves or the three rescued seamen or both groups that returned to Arklow, giving credence to some earlier reports, is unclear

A number of articles appeared in various newspapers, some just scant, others quite detailed. The later articles, appearing during the first two weeks of April, began to refer to the wreck site as being, ‘off Wicklow’.[Note7.] The North end of the Arklow Bank was often mistakenly referred to as the Wicklow Bank(s) by journalists, but more correctly, these are patches of very shallow sandbanks which form the India Bank further north and northeast of Wicklow Head.

Later again, on April 17, another article stated that the Linen Hall had been wrecked on the Wicklow coast and that the ‘money had been recovered’. Regarding the ‘money’, this statement proved to be incorrect and would seem to have been deliberately put out in order to subdue interest in the wreck, after the reporting of so much gold being aboard the schooner.

The money had not been recovered, and more to the point, George Drevar believed that it had not been recovered and that the Coastguards at Wicklow were still watching over the wreck.

Note 7. [The greatest part of the Arklow Bank is situated ‘off Wicklow’. A lower more southerly portion could be described as being ‘off Wexford’.]

To be continued…

Lloyds & Drevar & Friends at Howth

The article misrepresenting the fate of the ‘money’ on board the Linen Hall, was probably prompted by George Drevar. His earlier letter to Lloyds informing them of the loss of the ship and the cargo of gold, insured by them for the unexplained low premium of, ‘7 shillings and 6 pence in the pound’ – almost only a third of its value, had initiated a prompt reply. Most commentators were of the belief that the under-insurance was a cost-saving exercise. Clearly a man with at least two hats of responsibility in this affair, a director of the BoI and agent for Lloyds in the capital city, the Committee recommended to Drevar that an ‘experiment should be made’ to recover the gold.

Another large harbour project was taking place north of Dublin, at Howth. It was intended to be a hopeful competitor with similar works to those at Kingstown for the Dublin mail and packet service, and the BoI was in charge of handling the finances for the project. Mr Drevar rushed off a letter to the Howth Harbour Commissioners on April 14, requesting the use of their largest boat and a diving bell, in order to proceed to Arklow on an ‘experiment’ to dive and recover the gold. A special meeting was convened in the Custom House by the Commissioners over a weekend, on April 15th, and permission was granted. [Notes 8,9.]

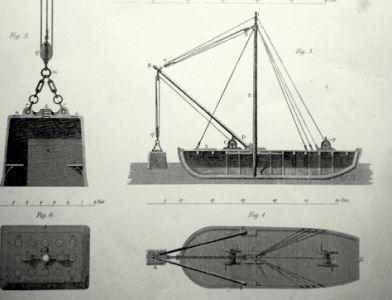

‘The Bell’, essentially a diving platform barge/lighter with a crane, was built in Morton’s Yard, Grand Canal Basin in 1816 for the Howth harbour works. This bell lighter was 60 feet in length and a little over a 100 tons. Crucially she was 20 feet across and drew less than 6 feet. As it was only designed for the erection of harbour walls, it had no propulsion. The diving bell was loaded into the Bell’s hold with the utmost urgency, and little apparent concern was demonstrated for the impact its loss might have on the harbour works. The cost was underwritten by Lloyds through George Drevar, who promised to make good any repairs etc..

The Bell, diving lighter built by Mortons of Ringsend for howth Harbour Commissioners 1816. [Note 8A]

Now, an ‘expedition’, hopefully blessed with fine weather, would have to get on to the Bank beside or over the wreck, lay down secure moorings, lower the diving bell with the men inside, and hack away at the deck or the hull of the ship until they broke into its hold to retrieve the two boxes of gold. Although the diving bell could be pumped constantly with air, the plan was optimistic – but given fair weather, possible nevertheless.

Note 8. [The Howth Harbour Commissioners usually held their meetings in the Custom House, Dublin. To hold one on a weekend was not usual. Shortly afterwards, the Examinator of Informer Books, Mr Kelly, notified the Commissioners that they could no longer hold their meetings in the Trial Room, belonging to the department of Customs & Port Duties. A room with some embarrassing secrets, perhaps, it is a statement that conjures intrigue. One wonders how far back the Informer Books went and just how many of them were there?]

Note 8A. [The certified drawings for The Bell by Mortons, are identical to this image of a diving bell lighter, which is believed to be the one built by Mortons.]

Note 9. [Remarkably, there had been a second petition for the loan of a diving bell boat before the Howth Harbour Commissioners at the very same time. This had been lodged by Thomas Gaffney of Ringsend, who had lost his smack, Joseph, transporting stone for the Ballast Board. Said to have gone down ‘within a mile of the lighthouse’, Gaffney’s petition did not warrant a ‘special meeting’ or ‘experiment’. He had hoped to raise the Joseph and his was a plea to avoid ruin and poverty that would surely follow after the loss of his livelihood. There was no indication in the Commissioners’ files that his petition was successful.]

Some years ago, an anomaly was highlighted by INFOMAR in a survey of Dublin Bay. Divers later discovered the remains of an old wooden vessel on the southern edge of the fairway to Dublin Port, in the position described by Gaffney – ‘a mile from the lighthouse’. There was no cargo of stone present in the wreck but its construction type seems in keeping with a large smack of the period. (See image above.)

Despite Thomas Gaffney’s pleadings to the Commissioners on hardship grounds, he subsequently seems to have done quite well for himself. Mr Gaffney of Thorncastle Street, Ringsend, died in 1824, leaving interests in an extensive property portfolio, a small fleet of fishing vessels, and a number of stone smacks – one called the Joseph.

To be Continued...

The Salvage of Drevar’s Gold

It is clear from several reports on the loss of the Linen Hall, that immediately after she had grounded, and probably after the men were rescued and returned to Wicklow, linen, a barrel of wine and bags of flour were recovered. It is possible for the linen and barrel of wine to have floated out of the wreck, but not the flour.

The ship had been almost totally underwater – why were spoiled sacks of flour recovered? Two plausible explanations come to mind; an eye being kept on future recompense for salvage, or someone was attempting to get at what lay beneath the sacks of flour!

It had been reported on April 17 that the gold was recovered, but Drevar was apparently confident that it had not. Notwithstanding incompatible reports, inaccuracy being a common feature of shipwreck reporting, a strange twist in events had already been reported in the Saunders Newsletter of March 30, which began as follows.

Shipwreck Upon Arklow Bank. (Dublin March 30.)

In consequence of the loss of the ‘Linen Hall’, schooner, laden with 2 cwt of guineas in two boxes, amounting to £25,000, and some flour and linen, which sailed out of this port on Sunday , for London, various rumours have been in circulation; many of them of the most absurd description, for several hesitated not to assert that the vessel had been intentionally stranded for the purpose, that some individual should enrich himself forever by one bold stroke. We have taken pains to inform ourselves of the entire particulars of this shipwreck, and are enabled to assert , that it was an inevitable misfortune, to which vessels on our coast are particularly exposed, when they are driven by tough gales blowing from the W. and by N. And coast along any of the banks to the North or South West of the bay.

Some omitted text ‘……’ and ended with,

‘A singular circumstance occurred in the course of the search made in the town for the gold, which is said to have been actually saved, relanded and brought to Dublin. Peace officers Robinson, and Crossley observed two boxes being conveyed on a dray through Bride Street, which exactly resembled the box wherein the gold had been packed; the weight was marked on the outside of them, and nearly corresponded also; certain therefore, that The Prize was now in view, they were immediately seized, but on investigating the vouchers, and examining the boxes, they proved to be rude copper pieces, imported into this country, for the purpose of converting them into Wellington penny pieces; they were consequently restored to the owner.’

An irony in this particular shipwrecking seems to have captured the imagination of some members of the public, when the following conversation was overheard;

“Oh what a terrible misfortune”

“By no means, on the contrary, it is quite fair speculation these times, and ought to produce ten per cent – being sunk money.”

The sardonic remark was not far wide of the mark, and maybe a lot more profitable than imagined.

It is obvious that there was some suspicion that the gold had been recovered from the wreck. A similar but real case occurred after the Earl of Sandwich left Dublin in 1765 when some of her crew mutinied. Killing passengers and crew, they then made off with a treasure of silver. The ship was stranded and the pirates landed at Dollar Bay, in the Waterford estuary. They returned to Dublin loaded down with silver but were eventually apprehended and hung.

Their bodies were displayed about the city and finally left to rot on the Muglins Rock, at the entrance to Dublin, as a warning to other sailors.

One could well ask, why a search for the boxes of gold was instigated if it was believed they had not been removed from the wreck. One might equally question – what was really in the boxes? Drevar must have harboured some doubt but proceeded with the salvage ‘experiment’.

The Tow

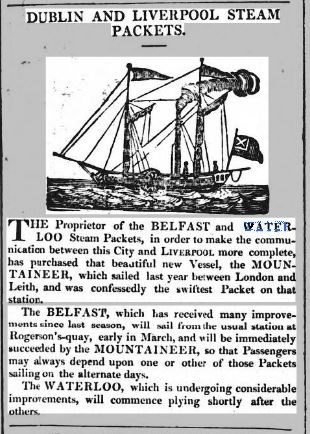

The Bell, diving bell, equipment and a small smack were all made ready for the expedition and handed over to Drevar by the harbour master at Howth, Captain Browne. The lighter and diving bell team were supervised by their overseer, Captain Wilde, and the tow of the Bell from Howth by the steamer Waterloo to the Arklow Bank was also arranged by Drevar.

On the face of it, it looked more like a staged demonstration for the relatively new steamer’s design of paddlewheel, and the speed it could generate if the patent was adopted – say on the cross channel packet runs!

The Waterloo, one of the earliest steamers, was owned by Mr George Langtry, the Belfast shipping magnate. Reflecting the source of his wealth, he was said to have owned a fleet of ‘linen boats’. Captain of the Waterloo, Robert Delap, hooked up the Bell at the west pier in Howth, and with some urgency, began the tow at 10 o’clock, on the evening of April 15. The tide was as with the Linen Hall earlier, about to turn and ebb, presenting the Waterloo with favourable conditions to steam a direct course all the way south, non-stop, between the Banks and the coast.

The small flotilla reached Arklow just before the morning light broke on the following day. Averaging 5-7 knots over the reported 45 miles, Captain Delap was delighted with his achievement. The Dublin man, John Oldham, was also aboard at the time and was equally proud but for a very different reason. It is highly likely Mr Drevar was also on the poop during the expedition to Arklow.

The Waterloo had been fitted with a prototype of feathering paddle, designed by John Oldham. Born a Catholic in Dublin, and said to have fathered 17 children, Oldham trained as an engraver, became an accomplished miniature artist, and above all, he was a talented engineer and inventor. He was employed by the Bank of Ireland as chief engineer after they had accepted his patent design for numbering banknotes. His paddle wheel design worked so well, as did his banking machinery, that his patent was investigated by a Parliamentary Committee in May 1822, and then widely adopted.

It was reported that the Waterloo got the Bell lighter to the site of the wrecked Linen Hall and that diving operations commenced immediately. Quite inexplicably, it was reported that the paddle steamer remained on-site for only two hours, and then returned to Dublin, reaching the Pigeon House at 1.30 the same day. How the divers and the Bell managed without propulsion, was not explained. It is extremely unlikely that such a vessel would have been able to remain moored on the Arklow Bank for any length of time unattended, and it is quite a mystery as to how it returned to shore.

There was no steamer stationed at Arklow, and the only explanations can be, that the Bell was either rigged to sail or she had been retrofitted with a small steam engine and paddle drive of her own.

There was no steamer stationed at Arklow, and the only explanations can be, that the Bell was either rigged to sail or she had been retrofitted with a small steam engine and paddle drive of her own. However she managed, it was reported that the Bell lighter was subsequently blown on to the Wexford coast almost a month later, on May 17, and was almost ‘a wreck’. She was saved by the Coastguards and returned to Dublin. It was returned to Howth on June 18.

There can be little doubt that the Bell worked the wreck when the weather allowed, and came to shore, probably at Arklow, for shelter, provisions and rest. Having experienced two terrible easterly storms, it must have become obvious that a vessel, such as The Bell, was unsuited to remain on the Bank for any extended period. Although Captain Wilde must have made some kind of report when he returned to Howth, there are no further archival details available of his diving expedition to the Arklow Bank.

To be continued…

The Clean Up

George Drevar notified Lloyds of the failure to recover any of the Linen Hall’s cargo, and they, in turn, returned a letter communicating their thanks to the Howth Commissioners. Drevar wrote to the Howth Harbour Commissioners on July 25, concluding their business in the matter of their ‘experiment’ to salvage the gold from the wreck of the Linen Hall, and transmitted the appreciation of Lloyds of London in the matter.

‘The Committee for conducting the affairs at Lloyds having commanded me to return you their sincere acknowledgement for the valuable and friendly assistance you afforded them by permitting them to use your diving bell boat and men while searching for the species lost on the Arklow Banks. I have the honour most respectfully to acquaint you of the same and take the liberty of adding my grateful thanks for the very prompt and liberal manner in which that assistance was granted.

Although I have to regret the unsuccessful issue of the search, I feel convinced that had the event proved fortunate, it would have been entirely owing to your kindness.

I have much pleasure in stating that Captain Wilde and the men under his command during the search, conducted themselves in the most exemplary manner, although from the nature of the undertaking they had many hardships to encounter and some serious difficulties to overcome. Be assured gentlemen that I shall long entertain a sincerely grateful feeling for the great confidence you reposed in me in particular on this occasion.’

Drevar’s use of the word ‘confidence’ might refer to the Commissioners’ loan of the Bell, divers and equipment. Or it could be construed as their complicity in keeping the whole affair private – or secret.

Lloyds had come out of the affair pretty worse for the wear, not that they would go to the wall or anything! They had to pay out on the loss of the ship and its cargo of ‘provisions’. They had to pay for the loss of the gold, luckily not the full cost. And they had to pay for repairs to the Bell lighter. They also paid for the hire of the lighter and wages for the men from Howth. That was the sum of the outlay by Lloyds for the loss of the Linen Hall and her cargo, but they had their own suspicions that something was not entirely kosher.

For instance; the Captain, first into the lifeboat, accidentally got separated from the wreck – not unique but unusual.

The captain and two crewmen were reported to have been picked up 40 miles from the coast of Ireland.

Without further clarification, this does not seem logical. Captain Payton and the brig Catherine were doing similar runs to the Linen Hall, operating between Belfast, Dublin, Bristol, south of England and London. The wind had remained westerly with a bit of north in it after the wrecking, and the tide was rising – travelling forty miles would have brought the lifeboat to the coast of Wales or thereabouts. If Captain Payton had been sailing to Bristol [Note 10.], his interception of the lifeboat could be explained, but why then travel back across the channel to Waterford. The wind and current either drove the small boat southward or some further clarification is required.

While the wreck lay on the Arklow Bank, it was obviously interfered with, and some cargo was removed.

Officials at Lloyds originally entered into their minutes that the ‘Linen Hall was driven on Arklow Banks’. The words ‘was driven’ were later struck out and replaced with ‘struck’.

This might seem like a minor correction but the difference is important. In 18-19th century maritime parlance, when a ship was said to have been ‘driven’, it meant that it was being propelled by the force of the wind. Less often, it referred to the force of the current. It also suggested, and not always, that the ship was under stress and even not capable of being steered properly.

A Lloyds official thought it his duty to replace the word, ‘driven’ with ‘struck’, as the ship was apparently under control at the time, and striking the Bank was most likely a case of negligence or something else. There was no attempt made to obliterate the word ‘driven’.

Unlike shipwrecks that had occurred on the Arklow Bank before, during that year, and in subsequent years, the remains of the Linen Hall was not auctioned. Lloyds were holding on to it.

Note 10. [Payton’s destination was also reported to have been London. And while this was an ultimate destination, ships often stopped at ports en route – such as Bristol. The Paytons were a well-known family of seafarers, some present in Bristol, and also sailing for Parsons & Hurles.]

The Wellington Penny

The case of the two chests of rude copper pieces that were arrested in Bride Street, Dublin, during the incident, and then returned to their owner, was interesting on a number of points. One was how the policemen had described the two boxes as being ‘identical’ to the ones loaded into the Linen Hall – how did they know this? The authorities had stated that the ‘rude copper pieces’ were intended for the manufacture of Wellington Pennies. They didn’t say whether these were to become legal tender or destined to become tokens. The presence of tokens in the financial system, used by commercial companies, military, religious etc., as a type of internal bartering coin, was still prevalent, but attempts were being made to phase them out.

The law and its administration can seem far removed from any semblance of justice, and ambiguous at times.

A number of curious cases began to appear before the police courts in Dublin after the Linen Hall incident. Holders of copper tokens and Wellington Pennies were being prosecuted for having them. Fraud was everywhere and it was illegal, it had to be stamped out. This type of petite fraud had been prevalent and a blind eye had been turned, till then.

In May, Magistrates were being advised that there was a large amount of forged Wellington Penny coins in circulation, also called tokens.

Later the same month at police headquarters in Dublin, Magistrates convicted Rose Ellis of having 12 ‘base tokens’. The charge was brought by the BoI. Rose got 3 months in prison.

It is curious how the BoI suddenly became active in the pursuit of those with ‘base tokens’, and maybe passing them off as legal tender.

The Wellington Guinea

The thing about Drevar’s cargo of gold was this. It was most likely to have been a ‘mixed bag’ of gold coins that had been received into the BoI over a number of years and were worth their weight in gold. Considered to be the oldest company in Europe, some earlier shipments of coins for the BoI were melted down by West Sons, Jewellers & Goldsmiths, Dublin, and shipped to the BoE in London.

In 1813, 80,000 guineas (George 111,) were minted to pay Wellington’s army. In 1822 they were probably still only worth their weight in gold. Today, not unlike some other guineas from earlier periods, these are now collectors’ items and are worth many times their weight in gold. Earlier shipments were known to have included a number of Spanish and Portuguese gold coins accumulated and hoarded by the BoI.

The two hundredweight of gold today is worth approximately 3.7 million pounds. A couple of hundred Wellington Guineas and other specialist coins thrown into the mix would sweeten the treasure that Mr Drevar and Captain Wilde were unable to recover, considerably.

The press put contemporary and future treasure hunters off the scent by stating that the money was recovered, but surviving records of the Howth Harbour Commissioners reveal that the guineas were never retrieved and the failure to do so, has remained buried, until now.

The Principals

George Drevar must have been a very interesting man. Living in a large house on Newtownpark Avenue, Dublin, he had a number of commercial interests around the City of Dublin and abroad. He was described as a Bordeaux wine merchant when he joined the Ouzel Galley Society in 1811. George Drevar had been much more than just a merchant, wine or otherwise, when he died seven years after the Linen Hall incident, in 1829.

Captain Graves does not appear as commander of a ship on the London run in Lloyd’s List during subsequent years. As this was quite a common name in shipping circles at the time, it is unclear where Joseph Graves went.

Mate, Bibby (Richard?), would seem to have taken command of his own ship for Parsons & Hurles.

Thereafter, shipments of money between the Bank of Ireland and the Bank of England were transported by the Royal Navy – Kingstown to London.

The reader will notice that most of the players in this affair were mixed up with the Bank of Ireland in one way or another. Graves (3), Drevar, Oldham, and the Commissioners at Howth. It is not surprising to find the same names popping up repeatedly in such circles, even Drevar’s son, William, married into the Graves line.

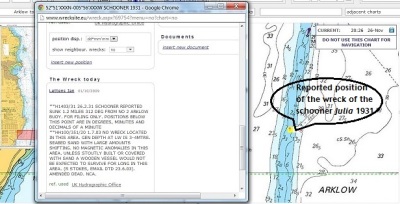

Fake or Fortune

The reader might find the attached chart of the Arklow Bank from the web site, https://www.wrecksite.eu/ indicating and reporting on the position of a wrecked schooner – tantalising. Unfortunately, this wreck is not the Linen Hall, but the Arklow schooner, Julia, owned by the Kearons and lost there in February 1931. [Note 11.] The wreck was discovered with its masts sticking out of the water and five crewmen missing, presumed drowned. A touch coincidental you might think, but the crew complement was quite common for coastal schooners of this size.

The loss was all the more sanguine after it was discovered that the men had been seen on the masts and some attempt was made by them to set fire to a part of the schooner, in order to attract attention. Their efforts failed, and it wasn’t until the passing Cymric had spotted the deserted wreck and reported after it reached Dublin, that the lifeboat at Arklow was notified.

Not the schooner Linen Hall of course, but fishermen stated at the time of the Julia incident, that a number of schooners had been lost in the same area through the years while attempting to either pass in or out of the Banks.

The farm of wind turbines planned for the Arklow Bank prompted several surveys of the seabed. Along with the dazzling results published by INFOMAR, under the National Seabed Survey Programme, numerous remains of shipwrecks have been discovered.

Is the Linen Hall one of them?

Note 11. [Synonymous with equally well-known names in Arklow, such as Tyrell, the tragedy took two of another maritime family, the Kearons.]

A Point of View

The facts of this unusual case of shipwreck, as presented, will undoubtedly suggest that something was not quite right. It is not for me to say, but one can’t help wondering if the two chests actually contained the amount of gold as reported by the Press, or had there been a switch made to ‘rude copper pieces? Any truth to the report of a subsequent attempt by the crew to salvage and ‘re-land’ almost-worthless chests of copper, would have made all involved, very nervous.

Was there a plot to ground the ship and team up some of the the crew and gold with a fellow-captain on a parallel course? It was indeed a strange case.

When considering the integrity of any of the players in this event, one should give careful regard to the lack of sufficient first-hand knowledge. Newspapers are one thing, official letters to and from individuals are another. But not unlike matters that are always intended to remain private, they are only ‘spoken’, and in confidence. Glowing obituaries appeared in print after George Drevar died in 1829. One in particular praised his ‘integrity and sound judgement which marked his decisions while an arbitrator and member of the Ouzel Galley Club…….and above all, he was an honest man’

If one considers that this was a genuine loss, as I believe it was, then the next question arises. Was there any subsequent attempt to recover Drevar’s gold? It seems inconceivable that no further attempts were made. The men and the technology were available. There were a number of skilled divers working on the harbours at Howth and Kingstown at the time. There were a number of professional salvor groups operating around the British Isles. The apparent dread of these Banks can be dismissed, as the wreck lay in quite shallow water and one had only to wait for suitable weather and diving conditions. Granted, the wreck might have been covered over by sand but the sand comes and it goes, and even then, there were known methods of moving sand. Local fishermen knew where the wreck lay and could find it more easily than most. In untold numbers of similar instances, the abilities of these boatmen have been grossly underestimated.

The library shelves of the King’s Inns are full of law books that contain more than a lifetime’s reading of cases they call, legal precedent. Meaning that, the outcome of a case that has gone before, can guide the outcome of later ones. Many a salvor has gone to the Admiralty Court on the bases of perceived precedent and lost his shirt, and his woes have also ended up on the shelves in the King’s Inns.

In the case of the Linen Hall, and assuming the gold is still there, then one third of it belongs to Lloyds, and the other two belongs to the Bank of Ireland. Notwithstanding, a salvor, a finder of the treasure could claim salvage – recompense for his endeavours. But there is a big if!

To legally go looking for a shipwreck in Irish waters that is more than a 100 years old, one must obtain a licence from the Irish Government. To dive and recover anything from such a wreck, one must first obtain further licensing agreements.

On the other hand, if one was to genuinely lose an item of value overboard, such as a boat engine say, and proceed to look for it, and then find a shipwreck accidentally, events could temporarily proceed in a different direction. One could report the find, and anything that was unavoidably retrieved could be deposited into the care of the Receiver of Wreck to await a finder and/or arbitration. Events might then converge as before, and any further visits or work at the wreck site would have to be licensed. Purchasing temporary rights by contract from say, the Bank of Ireland, would not automatically bestow right to work the wreck.

So, before you buy a boat or do the diving course, and having satisfied yourself whether it’s worth it, Fake or Fortune, visit The National Monuments Service – https://www.archaeology.ie/underwater-archaeology

If you ask me, the Fortune is in the Story.

EPILOGUE

A kind gentleman of unusual intelligence, who resides in south county Dublin, has been a friend and working colleague for many years. Although he is quite normal to look at, and converse with, he has an unusual capacity to absorb the intelligence of new things. He is gifted in many aspects of the computerised world, as well as being a self thought and excellent musician. My friend has an unusual fun hobby, which I only learned about in recent times – it is called, Dowsing.

The ‘gift’ is an ability that is much maligned, as it is considered ‘off the edge’, and can’t be explained, even though it is often used to find things. More commonly, water, but in reality, it is a talent that can be applied to a number of other interests.

‘X’ marks the position of the wreck of the Linen Hall, detected by ‘dowsing’. It is exactly 7 miles from Arklow, where some local newspapers reported it to be. It is also where the salvage vessel working the wreck was rescued by the Coastguards in 1822.

Curious, I ventured to asked him if he would be interested in attempting to locate some shipwrecks. The results were staggering. I then asked him if he wouldn’t mind trying to locate the remains of the Linen Hall, using this talent. He agreed, and asked me to supply him with a map of the general area where the ship was believed to have been lost. I did, the Google map as shown, was supplied, and he returned it with ‘X’ marks the spot. Previously unknown to my friend, the spot was exactly the distance from Arklow that one local newspaper reported the wreck to have been, and the area where the salvage vessel previously mentioned, had been working over the wreck!

The question arises. If Dowsing for shipwrecks proved to be accurate, would the ‘black art’ have to be licenced?

REFERENCES.

Various newspapers of the day, UK & Ireland.

Lloyds’s List, Losses, and Registers, 1819-1824, at the Guildhall Library, London.

The files of the Office of Public Works. OPW series 1. Dublin.

The files of Revenue and Customs, Series 1,Public Records Office, Kew. (Courtesy researcher, Justine Taylor).

The Howth Harbour Commissioners, HHC, series 8. Dublin.

The Bank of England archives.

The Revenue, Customs & Coastguard records in Ireland and the UK were searched, and no reference of the Linen Hall incident was found.

A South County Dublin Dowser.

No reference to the ‘Informer Books’ has been found in Irish Archives or those in the UK. The fire that destroyed much of the Customs House building in 1922, may explain their absence.

Genealogist/researcher, Enda McMahon made a valuable contribution to aspects of the Ouzel Galley and its members.

And a little bit of poking around.