At 2.30 PM, Sunday, September 7, 1845, a large public meeting was convened at Kingstown [Note 1.], on the property of builder, James Nugent. The topic was Repeal of the Union, and a large crowd with a number of celebrated speakers attended. Among them was the colourful emancipationist, Thomas Steele, who stirred the crowd with his captivating oration. Thomas Steele was a close friend of Daniel O’Connell and was not only a consummate nationalist but an inventor of sorts. He had been called by a Siren from the depths and spent much of his time in diving bells perfecting underwater lamps and speaking systems, and making novel improvements to the diving bell itself.

During his oration, he remembered that in December 1839, during pursuit of his underwater experiments, he descended to 7 fathoms at the end of the East Pier at Kingstown Harbour, where the new lighthouse was being constructed. Having completed his experiments and discussed the origin of the harbours’ name, ‘King George’, he toasted his two fellow harbour divers thus. ‘My brother divers , what the blazes do we care about King George the Fourth, but as we are snug and comfortable and cosy on the bottom we will drink (Sherry) the health of King Dan (Daniel O’Connell). And we did that night drink nine cheers, drink the health of the father of this country at the bottom of the sea. (Vehement cheering.)’

During a long speech he applauded Kingstown, it’s beautiful harbour and views, the advancement of the railway and steam ships facilitated by the new piers and a magnificent harbour of refuge. During the speech he referred to ‘his friend Mr Gibbons, your resident engineer.’ [The Board of Works engineer responsible for the harbour works, it was undoubtedly Mr Gibbons who arranged for his decent in the Kingstown diving bell with the harbour divers.] Steele continued his praise for Gibbons and his ‘beautiful plan’, which the engineer was developing for the ‘improvement and increased security of your noble harbour’.

Driven to bankruptcy by his passions, Tomas Steele died three years later after attempted suicide.

Mr Gibbons plan for Kingstown would become known as the Carlisle Pier. A friend to the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company and some railway companies, the pier had been conceived much earlier than any of us have realised. Gibbons’ plan envisaged that the pier would provide a complete and almost seamless efficient connection between the two capital cities, London & Dublin, not to mention the adjacent counties of both countries, thus providing a myriad of commercial opportunities. Despite many attempts to frustrate the project, to hijack it, to control it, it finally came to fruition by the tenacity of Barry Gibbons and his friends in Irish commerce. The project exceeded all expectations and the beautiful granite pier remained commercially viable for over a century. The Board of Public Works also remained undeterred.

Who was Gibbons? Barry Duncan Gibbons was born in Kinsale, Cork in 1798. He began contracting in public works in 1828, when he superintended the extension of the pier at Kilrush under Alexander Nimmo. The Board for Public Works was formally established under an Act of Parliament, 1831, entitled ‘An Act for the Extension and Promotion of Public Works in Ireland’ and Barry Gibbons began an esteemed career as a civil engineer, serving with a number of very prominent engineers. In 1832, Gibbons became resident engineer for the BPW at Dunmore, county Waterford, during the construction of another pier designed by Nimmo. In 1833 he returned to Kilrush and married Anne Brew, sister of the talented authoress, Margaret Brew. Gibbons became county surveyor for Wexford in 1834. Moving northward in 1838 to Kingstown, he became resident engineer there, and established roots.

Another Act was passed in 1846, authorising a huge expenditure for the construction and repair of piers and harbours around Ireland. Gibbons was put in charge of the project and promoted to principal engineer with the BPW. He also consulted for a number of private railway companies and despite being offered lucrative permanent employment in the private sector, he chose to remain with the BPW and his work there.

Gibbons travelled the length and breadth of Ireland during the Famine years, planning, consulting and building harbours and piers in order to improve the prospects of fishermen in some of the most remote regions of Ireland. He was also prominent in the design of bridges and promotion of various drainage schemes to improve the land. A man of sound judgement, an excellent listener, generous, and possessing a unique willingness to involve the local community in their construction projects. As the repeated testimonials confirm, he became a very popular and thoroughly well liked figure throughout the country, particularly in Wexford and Waterford.

The story and record of Barry Gibbons’ work is extensive and can be traced in the newspapers of the day and the surviving archives of the OPW (‘Board’ was later replaced with ‘Office’.) As a catholic, to succeed in the professions at such a time in Irish history, was not an easy accomplishment. He was self made man and succeeded eminently. Never wearing his religion on his sleeve, he had many friends and admirers amongst the Protestant and Catholic communities alike, not least in the Royal Yacht Clubs at Kingstown. Barry Gibbons had several addresses while at Kingstown, his last being at No. 2 Connaught Place, overlooking his beloved harbour.

The Traders’ and Victoria Wharfs had just been completed when work on the New stone pier began. Despite Gibbons earlier work, preparing and laying the foundation of his ‘beautiful plan’, the New Packet Pier, it is generally believed that this was commenced in 1853, then stalled for more than a year due to objections represented by a fellow engineer, and was finally completed in 1855. This is not entirely accurate. The pier was dogged by bureaucratic delays that were partially the result of jockeying and impeding forays in Parliament by representatives of competing Steam packet and railway companies. The New pier was ‘partially available’ for berthing in 1857, and officially open for service in 1859. The attractive ironwork and canopy was not fully complete until 1862, the year Barry Gibbons died.

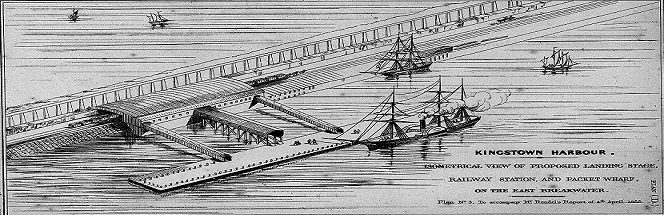

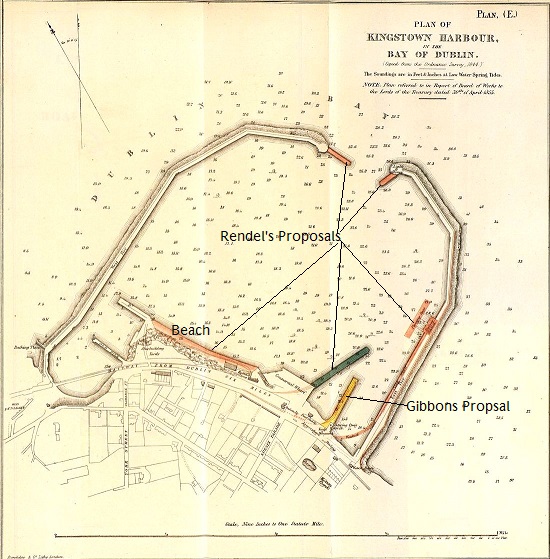

Reciprocal works had also commenced at Holyhead around the same time, and it was expected that the two packet piers would be developed and completed simultaneously. The pier at Holyhead was designed and construction supervised by the engineer, Mr James Meadows Rendel. Born in the England, he was a respected engineer who kept a watchful eye on works across the channel. Mr Rendel expressed the view that Mr Gibbons’ design for the pier at Kingstown was unsuitable, and some parliamentarians were minded to put down questions in the House. The BPW halted construction at Kingstown and the familiar machinations of Enquiry began.

As these were government backed projects, professional disagreement was unseemly, and Gibbons was instructed to meet Rendel on site, to collaborate and exchange views. Rendel remained stubborn and continued with the view, that Gibbons’ plan was unsuitable. Mr Rendel then laid his own design(s) before the Board. Two bites of the cherry no less. [See designs] Gibbons of course, took care to point out the unsuitability of Mr Rendel’s plans. Except in Rendel’s plan, there was ample justification for contrary opinion.

The foot dragging continued, the papers flew, and a meeting of minds remained elusive. Gibbons was doing what Gibbons had become well know for – building piers. His work had been faultless and his professional opinion was sought across many spheres of engineering. The disagreement and delay was hitting the newspapers – adjudication became urgent.

The Royal Harbour was just that – and the Admiralty stepped in to resolve the dispute. Two eminent Royal Naval surveyors were appointed to adjudicate; Captains Kellet and Frazer. Apart from all of Rendel’s additional proposals and massive increase in cost, there was no contest, and both surveyors came down decisively in favour of Mr Gibbons’ design. It is clear even to the not so expert, that Gibbons’ design was superior in a number of respects and presented minimum difficulty coming and going from alongside during strong winds from all quarters. [Both engineers were unaware of the difference bow and stern thrusters would make in the future.] The diving bells, lighters and masons resumed work, laying their huge granite blocks and the pier was finished for ‘partial use’ in less than two years.

It will have occurred to the reader that we are making a point here. And it is this. This pier had many titles – New Pier, Packet Pier, Stone Pier, and after the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Earl of Carlisle, the Carlisle Pier. Less known now but very popular then, it had another name – it was also known as, ‘Gibbons Pier’. More to the point, it was known as the Gibbons Pier well before it was ever called the Carlisle Pier. A certain reluctance to use the Carlisle title lingered after completion, and the double naming continued until Barry Gibbons died in 1862. It is admitted that Mr Gibbons was a very popular figure and his name just stuck, despite pressure to stick with another Pier. Gibbons does not appear to have been an ‘official’ name for the pier, more, one of affection.

Nevertheless, the first time it was called the Carlisle Pier was in August 1859, when the handsome troop ship, HMS Himalaya, bumped into it and cleaved a bit of wharf furniture. The first time it was referred to as Gibbons Pier, was in June 1852, and even carried the title in some commercial respects; ‘…charging a shilling for a jaunt from Gibbons Pier to the Kingstown Railway Station.’ Prior to the visit by Queen Victoria and family to Ireland in 1861, the Irish Times reported in July, that they would ‘…land at the Carlisle, better known as the Gibbons Pier…’ And although Lord Carlisle was a frequent traveller on the mail packet boats, according to the logs of the D.P.Co.’s vessels, their masters were still referring to the pier as the ‘new jetty’ or ‘new pier’ until at least 1860.

Except for the occasional benevolence bestowed on some of Kingstown’s citizens, there is scant evidence that Lord Carlisle had any particular interest in the development of the new pier. Despite a trawl of OPW, Series 1 & 8 [‘Board’ was later dropped in favour of ‘Office’.] Archives, Kingstown Town Commissioner minutes, Chief Secretary’s Office Registered Papers, and extensive search of newspaper and literary databases, no record could be found of a proposal to name the pier after Lord Carlisle. So it may have been that the New Pier could have been called after his Lordship purely by default – the unrestrained patriotic favour of some officials.

It’s Future

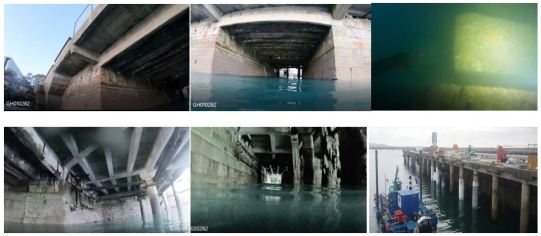

The name first given to the pier, ‘Gibbons Pier’, should be re established in honour of the services of a fine engineer and human being, who devoted his life to the betterment of the humble existence of coastal people right around Ireland and beyond, through a very difficult period in history. The horrible and decaying concrete that has been added to this magnificent cut stone pier over the years should be demolished and removed, to re expose a fine monument to Irish Victorian engineers and tradesmen that lies beneath. When Gibbons designed the pier, he claimed to have ‘future proofed’ it to handle larger boats as they developed. He was spot on, and to the untrained eye, the pier remains in remarkably good condition above and below the water. Silt, as always, remains a feature of general harbour maintenance.

There is no doubt in my mind that an attempt to build such a magnificent marine structure will never be undertaken in Ireland again! We are damn lucky to have it, and should cherish it. The beautiful wrought iron work and canopy (supposedly in storage) should also be restored in a modern setting that could possibly house a historical centre and market. Recognition of the ‘Kingstown Era’ might also be made by naming this area, ‘The Kingstown or Carlisle Hall’. Another Battle is with us, but it needn’t be like that – Ireland has matured far beyond old prejudices and it is time to move on. We can do far better than a ‘car park’ atop a magnificent Victorian marine structure. Let us cherish our heritage and improve on it for those who follow.

Images of decaying layers of ‘add-ons’. With sound Victorian granite block laying above water and unusual ‘stepped’ method beneath, at the Old Packet Pier. Images by the ‘well known diver’, J.P.

Barry Duncan Gibbons died in October 1862, and the citizens of Dublin experienced one of the largest funeral gatherings ever seen. He was buried in a prominent vault near the entrance to Glasnevin cemetery. His wife Ann adorned his headstone with a poignant epitaph, remembering that, ‘he was a good husband and warm hearted friend, his hand ever open to the poor, and his assistance ever ready for the lowly…’ She joined him in 1899. Sadly, the couple were childless and her name was never added to the stone.

It goes without saying, Barry Gibbons could not have accomplished all that he did by himself, and was joined by a number of trusted figures, skilled craftsmen and fervent admirers who helped him along the way. One of these men was, William Campbell, a Scottish Protestant, who came to Ireland after working on the pier in Portpatrick, 1838 – 1840. He was a carpenter diver, bell and marine, and had a number of other complimentary skills, such as underwater demolition and salvage. He was also a brilliant stone mason, leaving evidence of his talent around Ireland in the wonderful old stone harbours still surviving. Campbell was ‘by Gibbons’ side’ from the time he first contracted to him for Public Works in Ballycotton 1847, and worked on his ‘beautiful plan’ intermittingly. He also supervised the construction and completion of the magnificent RNLI cut stone lifeboat house lying alongside the East Pier – 1862. Gibbons travelled with Campbell and his son on various projects and trusted them implicitly. He was instrumental in having him appointed to the post of Harbour Superintendent at Kingstown in 1856.

Along with his family, and seemingly quite suddenly, William Campbell quit this important position and house that came with it, without any notice, and emigrated from Kingstown one year after the death of his friend and mentor, Barry D. Gibbons.

[William Campbell and his exploits is the subject of a new book by this author.]

[Note 1.] Contrary to the knowledgeable Wikipedia, Dún Laoire, Dunleary, or sometimes referred to as, Old Dunleary, was not renamed Kingstown. Instead, a ribbon of coastal area between Monkstown and Glasthule became the borough of Kingstown. Reference to Dunleary as a place or an address, was never dropped. The old harbour of Dunleary was subsumed into the greater one, Kingstown, not the ancient village or its residents. [Minutes of Kingstown Commissioners 1850-1860, and Thom’s Directories.]