An account of the harrowing loss of the emigrant ship, Pomona, 1859

‘Arranged side by side, they lay locked in the sleep of death, and the lifeless, which a few hours past were lighted up with life and animation, had become sickening objects, from which the heart recoiled…the eyes seemed directed to that haven where shipwrecks are never known – where no dread is entertained of a tempestuous ocean, and where no unskilful mariner can cast them on the dreaded sandbank.’

(The above is a contemporary narrative on the inquest held on, ‘Mrs Paxton, Female No.1’, at Blackwater. Wexford Independent, 1859.)

The Irish Times had been launched in Dublin one month earlier. The new broadsheet produced a running commentary on the horrific and unfolding details of this wrecking; the American clipper ship, Pomona, lost on the coast of Wexford. Adding some irony, gruesome details of the dreadful shipwreck, might have bolstered circulation numbers for the new entry, once again, demonstrating, that ‘every cloud…..’.

Providing some historical perspective, and legacy; his family, ravished by disease and famine in 1848, the eleven year old orphan, John Sisk, entered the building trade and established a construction firm in Cork, in 1859. This acorn would sprout into the world class building company, known today as, John Sisk & Son.

Three months after the Pomona disaster, John Maxwell was born in Liverpool, and would be best remembered as, General Maxwell, and for his brutal suppression of the Easter Rising in Ireland, and the execution of a large number of ‘Irish rebels’, in 1916.

In all probability, Henry Lavery would otherwise, never have made the acquaintance of the well known deep-sea Captain Paxton. The only thing they had in common at the time was that, they were both separated from their families. Joined by the same and separate tragedies, both men would die that day, but in different parts of the world, and would never see their families again.

A hard pressed and unwilling emigrant, Henry’s business as a publican, come wine and spirit merchant in Belfast, had ‘failed’. He had travelled to Liverpool, where he secured passage in steerage, on the sailing ship Pomona, for New York, in the hope of improving his situation. He left behind a wife and three young children, two girls and a boy.

The young boy, aged three when his father left for America, would become a world class and prolific artist, and one of a renowned celebrity duo; Sir John and Lady Lavery. Marrying for a second time, Lavery partnered the beautiful, Hazel Martyn Trudeau, daughter of a wealthy Chicago industrialist. Married twice before, it is said, she and her family, ‘came on hard times’, but after persistent pursuit by John, and equally persistent refusal of permission to marry, by her mother, she eventually became, Lady Lavery.

Apparently in recognition for the part Lady Hazel Lavery played, as a significant ‘backroom’ facilitator, between the Irish emissaries and London during the negotiations for the establishment of an Irish Free State, the fledgling State later commissioned her husband, John Lavery, to paint an image of a woman who would reflect and celebrate the New Ireland. John got the commission, and Hazel got to be painted – again. Lady Lavery appeared on Irish bank notes until the 1970’s.

A younger John Lavery may have referred to his father more often, and maybe more kindly in private, than what he offered in his autobiography, ‘Life of a Painter’. Published in 1939, it carried on the first page, this, the only personable reference to his father.

‘In considerable contrast to Ruskin’s father, who was also a wine merchant, he (His father, Henry.) seems to have sold out and cleared out at an early stage, leaving his wife and children to fend for themselves.’

His remarkable frankness later in the book, concerning his own uncharitable treatment of his unmarried sister, Jane, and her pregnancy, and his observations regarding the harsh conditions facing steerage passengers, as she emigrated in search of the unborn child’s father, in the 1870’s, are truly poignant. Her suicide soon after, haunted the artist for years afterwards.

On the other side of the world, Thomas Paxton, a well respected deep-sea captain from Williamsburg, was in command of the emigrant ship, Coosawattee (Savanah), and berthed at Bombay. He had arrived in India in the beginning of January. The registered owners of the ship were, J.R.Wilder & Co. Its operating agents were, the Tapscott Line. She was due to turn around for New York, where the captain had arranged to meet his wife and their three children, who were sailing from England on another Tapscott emigrant ship.

In the spring of 1859, the rest of the Paxton family booked cabin accommodation on the American sailing ship, Pomona, at Liverpool, for their transatlantic reunion with Captain Paxton. The events which unfolded amounted to a cruel double act by Fate, or just coincidence, which prevented any member of that family ever meeting again.

Emigrant Cargoes

Regarding cargoes for which these ships were designed to carry, it might first appear, that there was a conflict of purpose. As running ships was intended for profit, and given the nature of migration at the time, journeys eastward were not expected to carry large numbers of passengers. Instead, they were designed for the transport of bulk cargoes. The return westward voyages were also bulk, but of a different kind – emigrants.

Amongst a variety of cargoes, such as grain and lumber, these big sailing ships also left America with cargoes of cotton for Liverpool. They returned with a variety of general products, often stored low in the ship, along with hundreds of emigrants, looking for a new life of opportunity, in America. This meant that, there could be little concession to the comfort of the returning human cargoes, as the outgoing bulk cargoes, could not be accommodated economically in lots of cabins or permanently divided spaces for passengers in the bowels of the ship.

The conflict was easily settled by the shippers – whatever paid most would be shipped, so there was often a mix; ‘general cargo’ and emigrants.

The issue concerning the transport of the emigrants was; the ships were not constructed for the comfort of a large number of humans, but for the transportation of bulk cargoes – of many kinds. Some were constructed with more consideration for emigrants than others – stalls that were easily erected, but providing only ‘steerage’ accommodation. Even if you could pay more, there were few cabins in these vessels.

Provision of food during the voyage was often optional, again depending on money and ticket. Provision of sanitary conveniences, was abysmal. If you boarded in good health, you were lucky to reach the New World in a similar condition.

Although things had moved on somewhat, from the disaster of the earlier famine years and before, conditions for travellers on ships were sometimes far worse, and some journeys were purely a matter of survival. After mounting numbers of deaths from disease, and even starvation, Governments intervened, and forced shippers to improve conditions for travelling emigrants. The measures were basic to begin with, and often ignored once a ship was at sea. The move nevertheless, was the beginning of groundswell of change in the right direction.

—

It could be said that, many of the major ship owners during this period, had become wealthy, from their own and ancestral activities in the slave trade. It could also be said, that their attitudes to human cargoes, were dragged screaming into a new era. What helped to focus their attentions considerably, was the sheer number of them in the business. Competition was a great motivator, and for the moment, the traveller was beginning to benefit from improving shipboard conditions.

Apart from the meagre statutory rations, of which you might frequently only get the biscuits and water, an emigrant vessel often supplied additional food, at a profit; or you could bring your own. The provision of meals was Dickensian, dishing it out to passengers from large cauldrons, when weather conditions permitted. Preparing and cooking food was sometimes franchised to a cook and designated groups of emigrants, who might bring their own food, and have this cooked for them. An outbreak of fire on a ship, was a dread, and precluded any unapproved attempts to heat or cook food by individual passengers. All of the cooking was done on braziers or ranges, up on the main deck, in the ‘houses’ or ‘cabooses’, where the mood was often highly combustible. Weather conditions, and the situation of the ship and its crew, dictated meal times, or the lack of them. The ‘ship’s cook’ prepared food for the captain and the crew in a separate part of the ship.

Statutory regulations for commercial ships had not yet reached the point, that the provision of a ship’s doctor was compulsory, but many large shipping lines employed them. Their presence on a voyage however, was not always obvious. Regarding the hundreds of steerage passengers in their care, aboard an emigrant vessel, their duties rarely exceeded ensuring adequate ventilation, and maintaining basic sanitary conditions. And just as with the cook, passengers were even encouraged to provide their own doctor, one who would receive free passage in return for his services.

[In the case of the Pomona, there is reference to the ‘ship’s doctor’, Dr Kelly. The ‘ship’s doctor’ was also reported to have been, Mr Fox.]

Steerage, considered to have been the cheapest form of accommodation on a ship, it was a term often advertised in context with other classes of travel; ‘First Class’, ‘Second Class’, and then ‘Steerage’. Even by this time, the awful conditions still endured by steerage passengers, continued to exercise lawmakers into legislating basic conditions for travellers, which was helpful, but the outcome often ignored. The term ‘steerage’ had received such bad press, that shipping agents were re-packaging it as, ‘Third Class’.

A full range of accommodation advertised, often gave the impression, that the ship had considerably well appointed space for all passengers, and that ‘steerage’ or ‘third class’, could only be but humane, in such a well appointed vessel. Whereas, in these clippers, the bulk of passenger spaces was often only steerage, with very few cabins for those passengers who were connected, and financially better off.

A migrant’s fare might be paid or subsidised by a landlord, seeking to clear his estate. A tenant or migrant might agree to an indenture agreement, made through an agent on behalf of a prospective employer. One who would pay for the passage – and then recover the cost over a number of years through indentured labour. Indentured servitude was disappearing, but still employed in some British and American colonies. The rounding up of labour at some of these points of disembarkation could be described as little short of kidnapping. Quite ironically, even today, policies and operations of migrant labour continue to be a trade in shame.

On the plus side, some American counties were offering emigrants tracks of land for agriculture and the production of lumber. In slightly different forms, the practise eventually became widespread throughout these emerging New Worlds.

In the mid Victorian period, passage in a cabin on a ‘clipper’ cost about eighteen pounds, and seven to eight in steerage. Much cheaper could be had – at a risk. Expressed as a percentage of income, it is estimated that the cost of passage was actually reducing at the time. However, it is interesting to note, that this price hardly changed at all, for the emigrants who travelled during the wave of mass emigration, on the ‘assisted passage’ schemes, one hundred years later. So relatively, you might say that, it was far more expensive for an emigrant to reach America in the mid 19th century, than it was for one to reach Australia, one hundred years later.

The stark reality was; the wealthy were travelling – the poor were fleeing, and these emigrant ships were appointed accordingly. That was, in a manner likely to maximise profit from their bulky cargoes, human or otherwise.

An Emigrant’s Journey

Given the basic design of road transport – carts and wagons, and a less than basic road infrastructure in many places, travelling to the likes of Liverpool from the interior of Ireland, or from the British Midlands and Scotland, was a journey of endurance in itself. Setting out on such journeys was nevertheless, only one of the first feats of endurance, during the long long trek, in the search of some hope of a new life.

Emigrants travelled from remote areas by cart or barge, or even just by walking to cities, like Dublin. From there they would take a sailing ship, or even a steamer by then, to Liverpool, experiencing their first taste of ‘steerage’. Then there was the wait, and the subsequent nights spent in the filthy hovels of Liverpool, before the arduous passage to America. And lastly, for those not seeking work at the point of disembarkation in the port cities, a final journey to the interior or west coast of America. Undoubtedly the journey required stamina; with children or in sickness, it must have been a nightmare.

If an emigrant had not already purchased passage at a ticket agent, say in Dublin, they had to do so at one of the agents along the bustling quays of Liverpool. Steerage could mean different things, on different ships. It might mean hastily reconstructed racks of communal bunks, hammocks, or just a floor space, on which to lay down with one’s meagre belongings. On some of these voyages, from departure to arrival, it was pure endurance. Many never survived the ordeal. Wealthy shippers who had learned how to pack humans during the slave trade, continued with their inhuman attitudes and practises towards their fellow man – without the manacles. The provision of basic requirements; food and water, suitable sanitary conditions, access to fresh air and exercise, all suffered and were sometimes nonexistent.

Hatches, a word, when used in connection with ships, came to mean different things on different vessels, at different times. When used in connection with commercial sailing vessels, it meant a large rectangular hole in the ship, through which cargo was lowered and then dispersed below. The term remains in use today. When the cargo had been loaded, the hole was then sealed up with planks and made watertight with canvas, and was said to be, ‘battened down’. Entrance to below deck by this way, could at one time be had by way of a temporary stairway. When deck houses were fitted on sailing ships, entrance to below decks could be had through a door inside, and a permanently installed stairway.

In terms of passengers below decks, in steerage, when it was reported that the hatches were ‘battened down’, this was meant to signify that access through the deck house to below decks was sealed; or in the case of no deck house, the hatch or hole to below, was battened down and sealed up. Seemingly a very cruel measure, it was often reported, that the terrified screams of those imprisoned below, could be heard above the howling wind and the crashing waves.

Not being able to escape through the scuppers fast enough, the seawater would pile up on the deck, and pour down through any leaky planking. One can only try to imagine passengers’ frantic but pointless search for any means of escape, which must have terrified their minds. In some cases of shipwreck, crew and passengers have been discovered compacted together, in far flung dead end compartments of a ship’s hull, having clambered there, in a hopeless attempt to escape the rising water. On the other hand, some that had experienced fair weather and a fast passage, and reported having, ‘enjoyed’ the voyage.

‘Battening down the hatches’ is a phrase often perceived, as a cruel action by the crew. The suggestion being that, they imprisoned the multitude of passengers below decks, in order to help save their own skins. It undoubtedly occurred, but there are however, two sides to the story.

During foul and stormy weather presents one side. A captain and his crew must have full command of the deck, unhindered access to the rigging, and to be able to operate the ship without having to care for panicky passengers. A clear deck was required, in order that the crew might best weather the ship against stormy weather, for everyone’s safety. Large numbers of frightened passengers milling around on the deck of a heeling ship, could be more than unhelpful, and quite likely lead to injuries or even disaster.

On the other hand, (a phrase I love so,) the ‘battening down’, was sometimes used to imprison large numbers of competitors – for the often scarce number of lifeboats on a ship in peril. And I am afraid, that it is the latter in both respects, which seems to have been the case during the Pomona incident, and became a major contributing factor to such a massive loss of life.

One must also point out, that there were a significant number of emigrant vessels, whose owners and masters made a respectable profit in the trade and also managed to retain their honour, without resorting to brutal treatment of passengers and crew, or the neglect of their ships.

The deplorable attitudes and treatment of passengers in steerage, continued into the next century.

Port of Embarkation

There were many ports dotted around the British Isles catering for emigrants departing for America and beyond, at this time. By and large, Liverpool catered for the highest number of emigrants departing from Ireland and England, and for many other places besides. Migrants, who had shuttled to Liverpool from northern Europe, joined the human sea of travellers, all trying to reach various parts of the world.

Waiting for passage, thousands huddled in the back streets and in the filthy unregulated accommodation of cities like Liverpool. Victims of unscrupulous agents and middlemen, they were often fleeced by merchants and purveyors of anything emigrants might require for their impending voyage. Waiting for passage, they were preyed on by thugs and shipping agents, who were known to oversell non-existent accommodation on ships. The practice of smuggling passengers was rife.

Probably not a peculiarity of the Irish alone, but a practise in every country, where making a profit overrides any other consideration, the treatment of Irish emigrants by some of their own countrymen, was particularly reprehensible. These were creatures who had originally set out as migrants, and managed to reach these ports of so much hope and as much misery, but had never left. Instead, they remained and exploited their fellow countrymen who followed. The phenomenon is well described by the author, John Morphy, who explained:

(Paraphrased) Having thought better of making his fortune in America, Paddy chanced into the bed & board business near the quays of Liverpool. With so many of his countrymen travelling to the city in search of lodgings before moving on, they would surely welcome the sound of a common tongue? With the house stuffed with his countrymen, sitting around the table with the drink still on it, Paddy would lay out the facts, and guide them through the necessary requirements for the journey of destiny, which lay ahead. A journey he assured them that, they were ill-prepared for.

“Och, boys, jewels,” said he, “but yez are in luck, I was down this mornin to Pine Street, and Misther Tapscott tould me that the finest ship that ever sailed for Amerikay will sail the day after tomorrow to New York, and that there was room left in her for twenty passengers, and ‘devil a soul more”…

The emigrants were in a city, the size of which they had never even imagined, in land they knew nothing of. They had the good luck to find themselves in the company of a fellow countryman, who would surely help them through the process – sure it was great. Paddy proceeded to take them around the different establishments, where they could purchase the necessary food, utensils, and whatever else might be required for crossing the mighty Atlantic Ocean. And finally, to help them convert their ‘useless’ money into ‘dollar money’.

All the while, Paddy’s divvies from the inflated prices mounted, along with his commission from ‘Misther Tapscott’.

Emigrant Shipping Lines

The newspapers were full of them. Advertisements for passage commonly covered a whole page in a newspaper. Notices were plastered in every place of congregation, advertising passage to all corners of the Kingdoms and beyond. Described as a shipping line, when Tapscott advertised all of the ‘First Class’ ships he was running, it didn’t mean that he owned all of them. Just that, he was an operating agent for their owners in that city, and maybe he ran one or more of his own ships, which was the case with the ‘Tapscott Line’. So the company, Tapscott, Smith & Co., Liverpool, was known in short, as the, ‘T.L. Line’(Repeating the word ‘Line’)

The ‘Tapscott Line’, was by far, one of the biggest in the business of shipping emigrants. Despite or maybe because it had offices in many countries, the company would seem to have gained somewhat of a reputation for itself. Criticised at the time, and since, for its ‘shady dealings’. Given that, there were enormous amounts of emigrants travelling, and equally enormous amounts of money sloshing around, it is probably not unexpected. But the company’s business reputation was almost global, and was well remembered for many years later, as this shanty might testify.

Heave Away My Johnnies

By John Roberts and Tony Barrand.

Oh as I walked out one summer’s morn, down by the Salthouse Docks,

Heave away, my Johnnies, heave away,

I met an emigrant Irish girl conversing with Tapscott

And away my bully bota, we’re all abound to go.

“Good morning Mister Tapscott.” “Good my morning, my gal,” says he,

“It’s have you got any packet ships all bound for Amerikee?”

“Oh yes, I’ve got a packet ship, I have got one or two,

I’ve got the ‘Jinny Walker’ and I’ve got the ‘Kangaroo’.”

“I’ve got the ‘Jinny Walker’, and today she do set sail.

With five and fifty emigrants and a thousand bags of meal.”

The day was fine when we set sail but night had barely come,

That every emigrant never ceased to wish himself at home.

That night as we was sailing through the Channel of Saint James,

A dirty nor’west wind came up and blew us back again.

We snugged her down and laid her to, with reefed main topsail set,

It was no joke, I tell you, ‘cause our bunks and clothes was wet.

It cleared up fine and break of day, and we set sail once more,

And every emigrant sure was glad when we reached America’s shore.

So now I’m in Philadelphia and working on the canal,

To sail again in a packet ship I’m sure I never shall.

Oh, but I’ll go home in a National Boat that carries both steam and sail,

With lashings of corned beef every day and none of your yellow meal.

The last few lines contain a brief observation on the welcome transition that was beginning to take place. Sail to steam, and governments that were entering the shipping business by sponsoring the migration of labour on ‘National Boats’. The move began a gradual improvement in onboard conditions for migrant passengers.

Shipping agents were not ‘behind the door’ when it came to overselling a ship, and their advertisements not only oversold the size of a ship, but the ‘comfort’ that might be expected on board, and also, the length of the passage. Commonly stating, not falsely, that the passage might only take a couple of weeks, were in fact, it normally lasted nearly a month, and even months, on occasions.

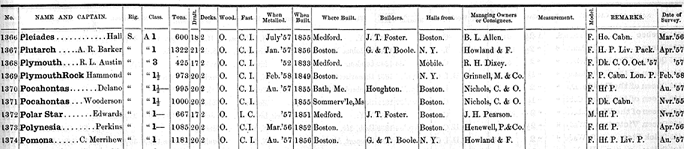

It was 1859, and listed at the top of Tapscott’s advertisement in the Liverpool Mercury, the next ship to sail with emigrants for America, was the Pomona on April 24. Clearly advertised at more than a 1000 tons in excess of her actual size, as is her sister ship the the Plutarch, for which there was no departure date given. The ships were declared ‘First Class Packets’.

For different reasons, gauging and recording a ship’s size, went through a number of administrative changes through the years. Despite the difficulty one might have, understanding these reasons and the methods of calculation, in different countries, the point to convey is that; the larger the figure of tonnage quoted, the bigger the ship was considered to be, and therefore, more likely to be safe and well appointed. Notwithstanding a ship’s size being bumped up for this reason, such an expectation was often misplaced.

Remarks which are attributed to ‘journalistic error’, prior to the ship sailing and after she had been wrecked, the Pomona was quoted as being within a range of sizes, that more than doubled the size of the ship. From 1000 tons, 1202, 1400, 1500, 1800, and 2500, to quote a few.

Upon completion in 1856, when the Pomona and Plutarch were registered in America, their respective tons burthen, were recorded as 1181 and 1322.

Tapscott’s advert also declared, that if you could get a ‘surgeon’ to take passage, he could have ‘free cabin passage’.

The law allowed the ship to be boarded twenty four hours before sailing, thus negating the expense of the overcharge for another night ashore, prior to sailing. Ashore, administration of ‘the law’ is one thing, on board a ship, its application is at the prerogative of the captain. It was not unusual for a captain to prevent boarding, until all of any cargo being carried was fully stowed away, and sometimes, not until the very last moment, did he allow a scramble aboard.

Aside from hundreds of emigrants packed between decks, the cargo stowed on the lower deck of the Pomona, was described as a ‘valuable general cargo’. It consisted of fabrics, such as wool and calico. It also included a large amount of iron and steel goods, crates of tin plates, and ‘measurement goods’. This last description, was a complicated calculation, involving the ratio between the weight and size of a cargo (still used today), which might have referred to the large amount of pottery goods, that were being transported to New York. Items, such as ironstone bathroom sets, kitchen and toilet ware, handless cups and saucers, jugs, and many more items, which can still be seen in her remains on the seabed today.

Come that Tuesday, the remaining available space on all three decks of the Pomona were packed out with 448 persons, passengers and crew.

[This ‘final’ figure for passengers on the Pomona, is in excess of earlier reports, but undisputed now. As in numerous other cases, the true figure could very possibly and even likely, to have have been greater.]

The Pomona had ‘three decks’. The one lowest, situated just above the bilges, was used to store any heavy cargo, which had to be evenly distributed and secured. The space was sometimes shared with the emigrant passengers. Eight feet above this deck, was the main deck, where most of the passengers were housed, and possibly some lighter cargo. Eight feet above this middle deck, was the upper deck. Under the masts there were two large saloon houses, one aft of the foremast, and another aft of the mainmast.

These ‘houses’ contained all the cooking fireplaces and utensils, and a saloon where the passengers gathered to eat or drink. Access was provided from the saloons to the steerage area below. The crews’ quarters and some of the ship’s stores were housed forward, in the area of the focsle. Below this, lay two huge piles of anchor chain in the bowls of the ship, and attached above, the ship’s anchors and the boasted new design of ‘patent winches’.

In the stern adjoining the poop, there was another raised house, and an aft saloon. Space on the port and starboard side provided cabin accommodation for first class passengers, which were described as, ‘state rooms’. The central area provided cooking facilities for the captain and crew. Accommodation for the captain and its officers was situated in the aft end of the ship, beneath the poop deck. Aft of the mizzen mast, and in the stern of ship, the ship’s steering and navigating equipment was fixed to the deck in an exposed position.

It was advertised that the Pomona would sail from Liverpool on April 24, but she was delayed for a further three days. In this case, it is likely that captain Merrihew allowed passengers to board on the Tuesday evening, before sailing, as it was reported that the ship cast off, on Wednesday at 5.00 AM, April 27, with the advantage of a high tide.

[It was later stated, that departure did not occur until the later time of, 1 o’clock (PM). This is contentious, as the ship is unlikely to have sailed against a tide, unless it had been towed well out into Liverpool Bay. High water in Liverpool, on the April 27, was at 07.30 AM.]

WSW

Some things in life seem certain, and others not quite so. It is certain that, a ship bound for America from the west coast of England, must first exit the Irish Channel, and clear the coast of Ireland. To do so, it must either exit through the North Channel, to the north of Ireland, if bound for say, Canada. Alternatively, as in the case of these clipper voyages to Boston and New York, they would exit south, through the Irish Sea and the George’s Channel. This southern exit proved to be the most treacherous for a large number of sailing ships.

Once having left Liverpool Bay, unless the weather is exceptionally ‘thick’, or the wind contrary, the north coast of Wales will remain in view until the northwestern tip of Anglesey is rounded, and Holyhead passed on the port side, until it finally disappears in the stern of the vessel. The most direct and popular course, which would see a sailing ship through the ‘gate’ of the George’s Channel, and past its craggy sentinel, the Tuskar Rock, was WSW.

Given the vagaries of weather, it was not at all certain that this course could always be maintained. As sure as one can be, given the winds that were blowing on April 27, 1859, fresh, ESE, and later from the less favourable direction, SSE; these should have proved favourable enough to see the ship safely round the Tuskar scarcely ‘60 miles away’. And without a change in tack or course direction, the ship should have made excellent time. The journey down the channel however, was always a question of, how far westward a ship would drift or ‘crab’, before it got to Tuskar?

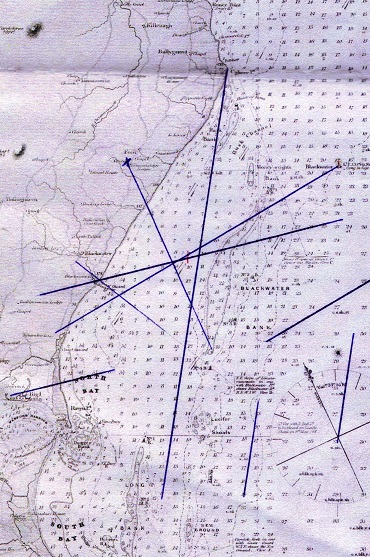

What had so often proved to be the case, when these winds increase in intensity and backed easterly during poor visibility, as they did for a time during the early morning of the 28th, was, that a ship can be driven dangerously more westerly than anticipated by some navigators. This fact has certainly been a major contributing factor in the loss of so many vessels on the chain of shallow sandbanks that are situated just a few miles off the coast, from Dublin to Wexford.

Fatally compounding the problem was – poor visibility. If the watch can see the danger in time, they might be able to avoid it. In order to help mariners observe coastal dangers, light buoys, lighthouses, and warning bells, were being established in danger areas. These were of great assistance to mariners, but in order to benefit from the light, you must be able to see it, and then identify which one it is. It is of no assistance to be able to only barely able to see a light, that it can not be identified. Equally, it is of little assistance, not to be able to see a flashing light well enough to determine its meaning! And what if you don’t see the light at all? Well, if there is a bell and you can hear it, it may be of help. Hearing it above the noise of a howling storm is difficult.

The optimistic outcome from a course, WSW set in from the tip of Anglesey, was to beat down the channel, identify the Tuskar, and then turn right for America. Not as simple as that of course, especially if you hadn’t spied the Tuskar before turning right. The measures taken in that event were; if practical, to bear off in a safe direction, usually south to east, and to reduce speed and sound the lead. When the light or lighthouse was eventually seen, or when it was determined beyond doubt, that The Rock was cleared, a new course westward could be set.

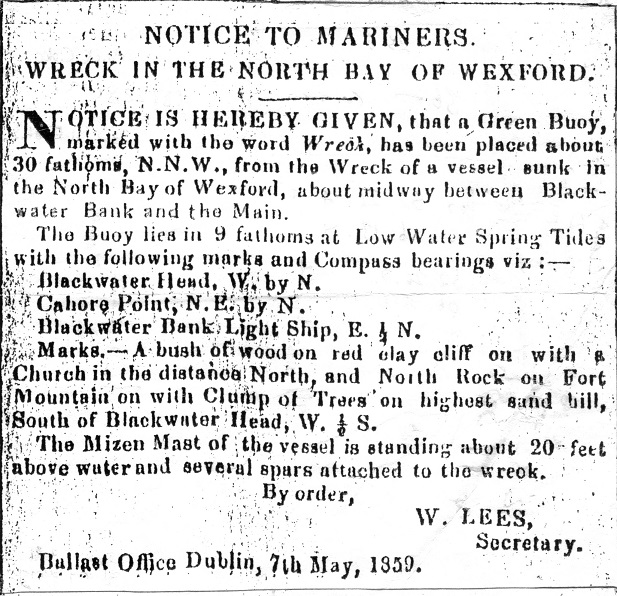

Sounds simple, but so many times, vessels missed the light, did not reach the latitude of the light, or did not see the light, and then ended up embayed or wrecked in the Bay’s of Wexford. In order to alleviate this problem, an additional floating light was established off the north end of the Blackwater Bank. Critically, the light did not appear until 1857, or as some had reported, ‘only some months prior to the disaster’.

Although the additional light at the Blackwater Bank became of indisputable value to mariners, it initially led to unforeseen problems, similar to those encountered here. What the authorities were aspiring to was; a string of guiding lights with distinguishing signals, situated at intervals along the outside of these sandbanks, from Dublin to Wexford. However, 1859 was still ‘early days’, and the

technology of ‘reflected light’ was not what it is today, as was the reliability of the installations themselves. It was also made clear, that mariners must become familiar with ‘reading’ the lights.

How it Happened

Appointed by the Board of Trade (BOT) to conduct the subsequent enquiry into the loss of the Pomona, their nautical assessor, Captain Harris, was not inclined to express unqualified confidence in the evidence given by the only survivors from the disaster. Lamenting the value of statements from the few reliable surviving witnesses, he reported; ‘and in this case for the most part they are illiterate seamen, devoid of all responsibility, and ignorant of the lights or position of the ship. We can therefore only form our conclusions from the evidence brought before us.’

Despite misgivings, it was nevertheless accepted, that the Pomona did not pass Holyhead until four or five o’clock on the evening of the April 27, a full twelve hours after the stated departure time for leaving Liverpool. This would seem to suggest some delay in the Mersey, or some other difficulty that may have delayed the ship, but not mentioned.

Some form of disagreement between the captain, and a member of the crew aloft at this time, was brought up at the enquiry, which suggested that the captain ‘called him down to lick him’. (An old form of punishment involving covering parts of the body with salt, and allowing goats to ‘lick’ it off. The goats of course, just kept going. By then, the meaning had probably moved on to ‘flogging’, but commonly administered as, a telling off, pay deduction etc., – maybe?). The mention of this indiscretion, was dismissed, and declared to be the business of a separate disciplinary enquiry.

The timing of the ship’s progress would have been more in conformity, if later testimony, putting the departure time at, one o’clock (PM), was correct.

The wind was fresh and favourable. Coming from the comforting direction of SE, it bode well for the Pomona and a quick passage through the George’s Channel. So favourable that, the captain remarked, ‘they would reach New York in seventeen or eighteen days.’

The journey down the channel progressed well at first, and many of the passengers were reported to have been in a celebratory mood. The night wore on, and some of the merrymakers retired, but a ‘large number, cheerfully inclined, had congregated together in the saloons and were singing and dancing up to a late hour. There being both a fiddler and a piper on board.’

The reporting reminded me of my own emigrant voyage in the Irish Sea; hardly a voyage, more of a ‘rough crossing’. The tears you’ve caused to flow are left on the quayside, and at sixteen, it’s a huge adventure in search of the elusive ‘golden opportunities’ abroad. The ‘opportunities’ that manifest into the hardest work you’ve ever imagined. The ship swayed, all the big men with their brawny arms and open neck shirts crammed the bars, singing and swaying. The beer in the glasses slopping and spilling, and the crew soon gave up on the increasing level of vomit, sloshing around in the toilets.

Funny thing, I didn’t get seasick then, and despite all the rough days on the sea since, it just never happened. I don’t know why that should be so, but I do have the greatest sympathy for those who can be prone to seasickness. For I have seen some reduced to a terrible state of incapacity, as a result. For those who keep returning to the sea, despite such a debilitating affliction, is a remarkable testimony to the lure of this relentless siren.

One of the few ranking crew members to survive the sinking of the Pomona, the third mate, Stephen Kelly, later relied on for some accuracy in recounting events, told the enquiry, that around 11.00 o’clock that night, a light was seen ahead. What was reported to have occurred next, didn’t make complete sense, and lead Captain Harris to his earlier remark, concerning the accuracy of witness’s statements.

Uncertain whether the light seen, was that of the Tuskar or some other, ‘the ship was hauled northward and eastward or away from the light.’ The manoeuvre, supposedly intended to claw away from danger until daybreak, when their position could be confirmed, was maintained until four o’clock in the morning. The weather then blew up considerably more violent, and easterly, and thickened with rain until the captain finally changed course and headed west – not for America, as he had supposed, but ploughed on, straight for the coast of Wexford just a few miles away. The ship and 448 souls aboard her, never reached America – only twenty four managed to scramble ashore on the beaches along the east coast of Wexford.

The evidence as presented, led to confusion. However, statements indicated that, a light was seen, the ship turned north away from it, and eventually west – straight for the coast. The mariners had confused their lights, and their actual position. A more simple summing up of events was that, the Pomona sailed down the channel on a course WSW, until it reached the Blackwater light, confusing it with the Tuskar, it then turned west, directly for the north coast of Wexford.

—

Assembled from the testimony of the third mate, Stephen Kelly, and the coherent recollections of the few reliable survivors, Captain Harris secured an answer to the interminable question. Was the lead sounded? The conclusion was that, it had not. He nevertheless deduced, and reported, that the ship was ‘properly found and seaworthy’.

The National Lifeboat Institution took issue with this particular aspect of the Board’s findings. Although the statutory number of lifeboats were on board the Pomona – seven, they claimed this number to be totally inadequate, being insufficient by at least thirteen, for the number of passengers being carried at the time. The boats in question, and others like them in widespread use, were also described as not being ‘real life-boats but sham life-boats’.

Any reasonable person might assume that the cause of the ship being wrecked might be spread proportionally, between the violence and thickening of the weather, the lack of visibility, and the negligence of the master and his crew, and maybe even the condition of the ship. Interestingly, these BOT reports always endeavoured to determine the state of the weather at the time of an incident, but never to attribute it as a ‘cause’ of the incident. Almost as if, a captain and crew should be capable of managing all and any weather conditions, they might encounter.

After the enquiry was concluded at Wexford, the Committee for the BOT concluded unequivocally; ‘…that the ship was lost by default of the master.’

Captain Harris, a man bestowed with determined and singular views, gave the enquiry the benefit of his simmering opinion, as to the cause of shipwreck.

While Lloyds agent, Francis Harper, a man of ‘30 years experience of many wrecks’, was explaining the series of events, that in his view had led to the disaster; ‘mistaking the lights’, the tide and the weather etc., captain Harris intervened impatiently.

‘This has ever been the story. No vessel is ever lost but from one of two causes – mistake of Lights, or unknown set of tides.’

Frustrated by the same old excuses offered on such occasions, one presumes that captain Harris might also have thrown in, ‘faulty compass’. In this case, the accuracy of the compass was not called into question.

Stranded on the Blackwater Bank

The Pomona struck the Blackwater Bank about five miles south of the Blackwater lightvessel. The water to the outside of this Bank is forty to fifty metres deep, and rises quite quickly to the Bank in some places. However, where the ship struck, the seabed rises to the shallows over a longer distance, of about two miles, before it reaches the shallows on which the Pomona grounded. This is approximately, four miles from Blackwater Head. Sounding the lead in such circumstances, would quite likely have given sufficient notice of travelling in the wrong direction.

The crew would have been first to notice. The impact would not have been like striking a rock – a sudden and audible crash, and a violent stop. Gaining on the sandbank, the ships progress through the water would have slowed through the mounting sand, bumping along the way, until she finally took the sandy bottom and lurched over to a halt. Despite expectations, it was reported, that the Pomona ‘grounded heavily. The inexperienced and those asleep below, might have been slow to realise that the ship had stopped, until it had heeled further over. Inexplicably, the cook, Michael Mulcahy, later stated that he went to his bunk for two hours after the ship first struck!

In hindsight, the ship’s predicament at this time could be viewed in differing ways. If the ship had grounded elsewhere, on a part of the Bank that was as shallow, but over a wider area, she may have become totally and inextricably stranded – rendering her unable to get off. If the vessel had then held together, a good deal of the passengers might well have got off or rescued, when the weather abated. The same result might have been achieved, if the captain had decided to deploy his two large anchors and chains, when she first took the ground.

The prospect of saving the ship and the passengers, must have weighed heavily with Captain Merrihew at this time. The alternative of not deploying the ship’s anchors, or waiting for the next high tide to lift the ship and clear of the sandbank, must have been uppermost in his mind.

The ship was stuck fast though, and remained that way through the night. The passengers rushed up on deck and ‘for a short time a wild scene of terror and confusion ensued.’ The captain and crew eventually restored ‘something like order.’ There were almost 400 passengers below, and this was the last reported comment about the situation of the emigrants as a whole, until their lifeless bodies began to drift ashore, after the ship began to break up.

The statements are confusing on the contentious issue – whether or not the passengers were ‘battened down’ below decks? Not addressed in any detail during the progress of the enquiry, but it must have been at this point, that the passengers, but not all of them, were battened down below decks. This would have been accomplished by securing access to the central hold, and the exits from steerage, through the deck houses. Despite a general belief that this was indeed the case, the cook Michael Mulcahy refers to some women coming up from steerage, and the third mate Stephen Kelly, stating that the pumps were manned by some of the male passengers. These may have been those who had already been topside, and never returned below.

The shore was only about four miles away from where the Pomona struck the Bank. It is low-lying, with the exception of Blackwater Head, and some coastline either side. The position on the Bank where the ship struck can easily be seen from the shore, and visa versa. Ordinarily, in easy sight of the shore and safety, but entombed within wooden walls and rising water, they could not see the shore, or be seen from it. The wind howled, and the rain sheeted across the pitch black sky. Nothing could be done, but to wait for daylight.

The wind and rain intensified. The sea bashed through the bulwarks and over the deck of the ship. With the vessel working dangerously on the bank, and the water pouring through the decks all through the night, we would have real difficulty understanding the terror felt by the hundreds of emigrants that were confined below for a further twelve hours.

Around 10 o’clock, the following morning, captain Merrihew gave the order to cut away the main and the foremast. This was a procedure that was quite common in such circumstances, avoiding the dangers created by the leverage of the huge swaying masts, and reducing weight and action of wind on the boat. The top of the Mizen was lost, but the lower part was retained in the event of the ship floating off, providing for a jury rig later, or a possible rescue from it.

The measures were insufficient however, to prevent the sea from continuing to lift and pound the ship on the sandbank. Despite perceptions of ‘moving sandbanks’ along this coast, this one hadn’t moved for centuries, except over and around the bones of shipwrecks. The pounding and cracking of the hull continued. The ship was badly damaged below, and the pumps were by then, permanently manned, in an effort to prevent the level of the water in the ship from rising.

The masts had already been cut away, high water had come and gone, but the ship failed to get off. Quite unexpectedly, but probably helped by the strength of the current over the Bank during the falling tide, the ship began to break free from the clutches of the sandy bank. She was then blown over the bank, and easterly towards the shore – but into deeper water.

Again, captain Merrihew was presented with a difficult choice. If the large clipper continued to be blown helplessly towards the shore, it would eventually ground again, and almost certainly become a total loss. But how far from the shore would it ground again? It must also have occurred to him that they would quite likely get much closer to the shore, and some of the passengers at least, would have a better chance of being saved.

A similar incident occurred the following year, and although there were fatalities, it had a more fortunate outcome.

The full rigged Lydia of Liverpool, struck the ‘Blackwater Bank near the spot where the Pomona foundered.’ In this case, the ship was blown on to, and then over the Bank, and grounded closer to the shore. A small boat put out from the stranded ship, but was swamped in the surf, drowning her three occupants. The remaining nineteen aboard were saved, when rockets eventually got a line to the ship.

Ten years on, again in the same place, another large American clipper, the Electric Spark, was run ashore. She became a total loss, but with very few casualties.

The captain’s motives were probably entirely honourable, when he chose to make an attempt at saving the ship, and who knows, maybe the passengers as well. But unfortunately, his actions condemned the ship, and almost every passenger aboard, to death. Events that unfolded during the wrecking of this ill fated emigrant ship, became what is probably the worst and most regrettable incident in the entire history of shipwreck from around the coast of Ireland, and is not ‘remembered well’ in the county of Wexford.

—

At the break of day, those on the deck of the stranded vessel could now see the shore, and those who had gathered on the shore, could see the large sailing ship grounded on their doorstep. Word was immediately dispatched to the lifeboat men along the shores of the county. With a relatively short distance to the shore, the Head, and the land now visible, the captain reportedly ordered his crew to launch the remaining life-boats.

Two of the seven lifeboats on board the Pomona, had already been washed away during the storm. Three more were stove in during attempts to get them out. Some crew were lost during the operations, one of them being Michael Hayes from Wexford – so near and yet so far, from his homeland. Only two remained, when Providence and hard work lent a hand.

There are quite a number of ballads commemorating the lore of shipwreck on the coast of Wexford. The ballad, ‘The Pomona’, collected by Joseph Ranson C.C. in 1937, was published in ‘Songs of the Wexford Coast’, and the following verse is just one, that is critical of captain and crew, and their action during the tragedy.

‘With her rigging and her bulwarks and her steerage torn away,

Wasn’t that a dismal sight to see in Wexford Bay?

‘Twas in that dreadful crisis her captain stood amazed;

With cruelty he bound them down to meet their watery graves.’

The Pomona Slips Off The Bank

The stern of the Pomona slipped off the sandbank, and the action of a favourable tidal current and wind, began to drag the remainder of the ship into deeper water. Whether or not it was because the ship was filling, or that the captain was making a determined effort to save the ship, he gave orders for the anchor(s) to be let go. It was suggested that, the reason for this manoeuvre was that, the anchors might bite, and then hold the ship. Swinging on the anchor, she might then have come round, and back onto the bank again, gaining some additional time for a rescue.

Considering, the conditions, and where the remains of the ship lie today, two and a half miles from the shore and one and a half miles from the inside of the Bank, having sunk at her final mooring, this seems to have been an overoptimistic assessment of their predicament. The distance from the Bank is too great for the length of available chain, as was the strength of the easterly wind.

Testimony and reports differ, as to whether one or both anchors were let go. In either event, one or both anchors ploughed into the sand, the chain(s) ran out, and the ship held. As the Pomona had gained almost two miles on the shore, the depth under her hull had reduced again. She might have drawn almost thirty feet by then, which meant, the same measurement existed beneath the ship. There is sixty feet over the wreck today.

It was reported that, there were ‘40 men on the pumps’, when the first of the two remaining lifeboats was lowered. Recounting this moment, and with surprising clarity and conviction of fact, Stephen Kelly’s declaration reads. ‘At 1.30 PM a long boat got out, when the cook, steward, boatswain and three others left in her.’ This boat set out from the stricken vessel with only six persons in it. It reached the shore where it overturned in the surf, drowning four of its occupants.

The passengers’ cook, (See also, Meehan, ‘passengers’ cook’.) Philip Mulcahy, from the neighbouring county, Waterford, who had been in the job for less than a week, and the boatswain, Richard Long, made it to safety. It was later reported that, the cook testified; ‘the ship’s crew gave no thought to saving the lives of the passenger’, not offering any clarity to which ‘crew’ he meant – the crew in his boat, the crew that followed in the only remaining lifeboat boat, or the crew they left behind?

With only one remaining life-boat, Stephen Kelly, in his sworn statement at Wexford, the day after he was brought there, told what happened next. ‘Myself, fifteen of the crew, and passengers, left the ship at 2.30 PM in the whale boat and landed at Blackwater. I expect the remainder of the crew and passengers are all drowned.’ The last sentence is odd, as it is in the present tense – and those left behind were almost certainly all drowned by the time it was reported to have made this statement.

[The crew that left Wexford on the paddle steam tug, United States, gave sworn depositions to the American Consul upon their arrival in Liverpool. The involvement and obligations to both jurisdictions in such circumstances, the UK and US, are interesting.]

[Stephen Kelly gave a sworn and signed statement to the Collector, Mr Cochlan at Wexford, and was published in several newspapers, verbatim. He, and the remainder of the surviving crew and passengers, travelled to Liverpool on the steam paddle tug, United States, before the official enquiry began. The fact that key witnesses could depart so easily from such a disaster, without being formerly questioned by the appropriate authorities, was found to be unacceptable by the subsequent enquiry, who recommended measures to be put in place, in order to prevent its recurrence.]

Struggles In The Surf

Now regarded as an official total number of survivors in this boat – it stands at twenty two. Newspaper reports on the number varied, and reported that ‘five’ were lost out of her. Reports published in Liverpool on May 4, announced the arrival of the, ‘the third mate, nineteen of the crew and four passengers.’

The last moments of the big ship, and all those trapped in her, were described by Mulcahy, at the inquest of ‘Mrs Paxton, Female No.1.’

‘…The last boat had not long got off when the vessel with all on board sank into the yawning abyss which opened its gaping jaws to swallow this multitude of poor creatures…’

Additional testimony put the final nail in the coffin of any doubt.

‘…No effort was made to save the women and children, the sailors were too busy saving themselves…’

The inquest proceedings on the body of Mrs Paxton, and the other bodies lying in the boathouse at Ballyconnigar, began on Saturday, April 30. It sat all day, and reconvened after services the next day. The testimony submitted by third mate, Stephen Kelly, and the ‘passengers’ cook’, Peter Mulcahy, was revealing, in that, it suggested that the departure of the two lifeboats had been under quite different circumstances, and had occurred within a short time of each other.

Mulcahy’s view was that, ‘The captain preserved great calmness, but the chief mate seemed desirous of abandoning the vessel.’ His testimony also suggested that, the first boat was an organised attempt by the captain to get a boat to the shore, in order to raise the alarm, and that the second was a desertion. At a time when, ‘The Bulwarks being then crowded with passengers half stupefied.’

It has always been difficult to attribute cowardice to any man in such circumstances, as one will remain unsure, just what might overcome the otherwise normal function of the mind, at such a time. However, despite Mulcahy’s view, that the bulwarks were ‘crowded with passengers’, the fact that there was no further mention of thronging passengers on deck, would lead one to believe, that the hatches and exits from below deck, had indeed not been open, or opened in time. If they had, it would have given those below, their final but maybe hopeless opportunity to save themselves. The low body count after the initial stages of the sinking would also suggest that this was the case.

Mulcahy’s boat was the only other lifeboat to get away from the sinking ship. It managed to get through the surf and landed safely on the beach at Ballyconnigar. The local inhabitants had already begun to assemble on the sandy pebbled shore, after the first boat had overturned, and spilled its occupants into the pounding breakers. The locals immediately began to render assistance to the survivors, who had got ashore from the second boat. During late afternoon and evening, the remaining few bodies were extracted from the surf on the shoreline, and brought to the local boat house.

This appears to have been the extent of the rescue and recovery during this initial stage of the sinking and its aftermath, and unbeknownst to the survivors and the rescuers, this was the last contact with any living person from the Pomona. With the two from the first boat, and this second group of survivors having reached the shore, it represented the total number who survived the wrecking of a large modern ship. She had been carrying four hundred and forty eight passengers and crew.

The small number of victims and survivors, who had gained the shore in these initial stages of the aftermath, were primarily members of the crew, along with some passengers who had been in cabins. Barring a few, maybe, it didn’t include any of those who had been ‘battened down’.

What transpired between the crew who remained on board, and those who escaped, was not recalled with any certainty. The separation, would suggest only two possible situations. One, that it was agreed and amicable, and the other that, it wasn’t. Captain Merrihew, with the first and second mate, remained on the sinking ship. As we will discover, it would appear that they might then have gone below out of the storm, perhaps in an effort to comfort the passengers, and to wait with them, in the hope of a rescue.

After The Aftermath

It was quite common after the loss of a ship, for accusations of excessive alcohol taking by members of the crew to fly. And this case was no exception. Reports appeared in several papers, suggesting, that the captain had been ‘drinking’ with the merrymakers.

[Today, sharing a seat at the captain’s table for food and drink, is considered, an honour. Suggested to have been almost criminal, the captain and his fellow diners aboard the liner Concordia, became the target of hatred in 2013, after the ship struck a reef and sunk – while they dined.]

Accusations of drinking reached ridiculous proportions in the Maine Temperance Journal, the following June, when it stated that, a statement had been received by them from the ‘mate J.P. Harwood’, accusing the ‘three Ist.class officers of being drunk in their cabins, and that the ship ‘sunk and they went down in their sleep.’ A surviving crewman by that name is not mentioned in any roll. The finding of the inquests or the BOT enquiry did not arrive at the view that any of the crew had been drinking. They did however condemn the crew for ‘deserting their passengers.’

The weather worsened and no further bodies, dead or alive, appears to have come ashore at Ballyconnigar, or visible in the vicinity of the sunken ship. The ship had not sunk straight away, but was reported to have disappeared within an hour of having come off the Bank, and entombed all those below decks, to a watery grave. The actual moment of the sinking, was given in testimony by the ship’s cook, Mulcahy, and makes frightening reading.

News of the catastrophe had spread almost faster than the coastguards could deliver it, up and down the length of the coast. The lifeboat station at Rosslare to the south, and the Collector of Customs Mr Cochlan, asked the owner, of the steam tug Erin, based at Wexford, Mr Devereaux, to tow the lifeboat the ten miles to the wreck. They however, could not set out in the prevailing conditions, and could do nothing more than keep up steam, and stand-to at Rosslare, until the weather abated.

The lifeboat at Cahore, was hopelessly situated ten miles to the north, and was transported by road to the beach at Morriscastle, nearly opposite the stranded ship. The lifeboat men launched several times, but were beaten back, time and again, by the force of wind, and the height of the breaking surf. The situation remained hopeless until the next morning, when the weather began to settle.

The number and category of the few victims that were washed ashore at Ballyconnigar and beyond, that day, was telling. The bodies of four crewmen had been tossed out of their boat earlier, and there were the bodies of cabin passengers. The bodies of the cabin passengers, Mrs Paxton and her three children, Thomas, Hanna and Lizzie, were recovered at Ballyconnigar, and Ballynesker, which is a little further south.

It is sometimes the case that, ‘truth is stranger than fiction’, and as misfortune would have it, so it was on this day. Mrs Paxton, wife of the deep-sea captain, Thomas Paxton, had died with her three children. On the very same day, her husband died aboard his ship, the Coosawattee, anchored in Bombay. The entire family was wiped out at sea in one day.

—

A regrettable action during any tragedy, it was reported that the body of Mrs Paxton was stripped of her fine clothes when it was washed ashore at Ballyconnigar. The accused was the local woman, Ann Kirwan, and along with her complicit husband, Thomas, they were promptly convicted of the offence at Oulart Petty Sessions. Both were sentenced to six months, with hard labour.

[To some, this sentence might seem severe, but when one considers other contemporary cases of stealing from shipwreck, were the accused could be arrested, put before the court, and hanged all on the same day, maybe the Kirwans didn’t do so badly?]

What struck me about this incident was, that which wasn’t stolen from Mrs Paxton’s body. Undoubtedly, Ann Kirwan had committed a repugnant act, but the woman did not steal the beautiful pair of gold earrings still being worn by Mrs Paxton, nor the large sum of money and other items of value, found later on her body by others. Exactly what she stole with the clothes, if anything, was not made as clear as you might expect. An issue with Mrs Paxton’s gold watch arose, but it proved difficult from the reporting, to determine exactly where this watch was first recovered, and by whom.

Stealing clothes from shipwrecked victims was not unknown in Ireland, or anywhere else for that matter. In fact, the whole episode was badly reported, and the fact that one newspaper was duplicating another, verbatim, did not help.

Newspapers reported that, Mrs Paxton had been carrying a large amount of money on her person, and the suggestion was that, this was the target of the Kirwans. We don’t know this to be certain, as long after the Kirwans were convicted, on July 4, newspapers were reporting that Mrs Paxton ‘was interred respectably, for a large amount of money was found on the person of Mrs Paxton.’

The ruling as reported in Freemans Journal, May 18, 1859, and copied from The Wexford People, is also worth noting.

‘Despoiling the Dead – At the Oulart Petty Sessions held on Tuesday last, Thomas and Ann Kirwan (husband and wife) residing at Ballyconnigar, were charged and found guilty of robbing the dead body of Mrs Paxton who was drowned in the ill fated ship Pomona. Six months imprisonment with hard labour.’

Other newspapers reported that, they were found guilty of ‘stripping the body’, – a noteworthy difference? It just seemed from reports covering the incident that, some antipathy existed between the office of the constabulary, and the local citizens. Given it’s not too distant history, and Wexford being Wexford, maybe this should not be unexpected.

The Pettit Sessions ledger did reveal, a constant stream of charges being brought against local people in Wexford at the time. Offences, such as having no harness on a horse, spitting, loose car, drunkenness, trespass. etc., seeming very petty indeed.

The ledger also reveals, that Anne Kierwan, and her husband Thomas, appeared at Oulart court on May 10, 1859, and were prosecuted by witnesses, Patrick Malone, and constable, John McNulty. The same charge appeared against husband and wife, which was ‘withdrawn’ on one page, and then re entered, with a slight differences.

Addressing the pair, the clerk read out the charge. ‘On the 29th of April 1859, at Ballyconnigar, you had on your premises several articles of shipwreck goods – one gold watch and rings – some wearing apparel shamefully removed from the dead body of Mrs Paxton, when cast ashore at Ballyconnigar from the ship ‘Pomona’ wrecked there.’

The reader will quickly note, the pair were charged with having the goods, but not for removing them from Mrs Paxton’s body.

They were found guilty, and sentenced to the six months hard labour. Despite fastidious record keeping, what the ledger had no facility to record was, any statements made by the accused. Exactly what happened in the surf during those dreadful hours will have to remain a little uncertain.

The ledger also reveals that, the Kirwans were not the only ones to appear at Oulart, for stealing from shipwreck. ‘June 2, William Shiel was charged with wrongfully carrying away or removing ‘Wreck’, contrary to the provisions of the Merchant Shipping Act 1854.’

—

The body of a gentleman, of middle age, was also recovered, as was that of a young man, estimated to be twenty five years of age. The ‘middle-aged gentleman’, may have been the body of Dr Kelly (first reported as Dr. Fox), the ‘ship’s doctor’, whose body was also said to have been recovered at this time. Barely visible, a six month old infant was also recovered on the shore. Which of the bodies was Henry Lavery, is unknown, but it was nevertheless recovered to the boathouse at Ballyconnigar, where he was waked with others.

Henry Lavery was subsequently identified by one of his family, who travelled to Wexford. His wife died three months on, and the children were farmed out to relations for rearing – literally, in the case of his son John.

Henry Lavery was buried with the other victims at Killila cemetery, a very small enclosure atop a small hill, immediately to the west of Blackwater village.

During those first recoveries, the body of a grey-haired elderly woman was tossed around in the surf, a couple of miles further south at Curracloe. After a confrontation of sorts, some local men supposedly refused to help in recovering the body – until they were paid. The body was recovered by a local constable and a ‘gentleman’.

More than a month later, identification of items found on a body that came ashore on the same popular holiday beach, indicated that it was that of Captain Merrihew. He had a thousand dollar bank note on him – believed to have been worthless!

Reports of the inquest, held by Coroner Dr W.C. Ryan on the captain’s body, appeared on June 6. It is held by local people that, divers reported having seen the body of captain Merrihew, still bound to the mast of the sunken ship.

At first light, and after the weather moderated, the steam paddle tug Erin, based at Wexford port, set out for the wreck with two lifeboats in tow. I have no doubt that the rescuers knew that the Pomona had already sunk, and harboured little hope of recovering any survivors from the wreck itself. Even so, the description of the scene they came on was pitiful. Hovering over the wreck, all that could be seen of the large ship was the remains of its mizzen mast, still attached to the submerged clipper ship. And still attached to the mast, fluttering in the breeze on a fresh morning, was an American pennant.

There were no bodies, alive or dead, to be seen anywhere. It must have been a terrible feeling for all the would-be lifesavers, as they hovered over the sunken ship beneath them, knowing that it must still have contained hundreds of passengers. The tug and lifeboats returned to Wexford without saving or recovering a single creature – but ‘entirely pleased with the execution of the boat.’

—

Criticism of some local inhabitants appeared in almost every newspaper. In the case of Ann Kirwan and her husband, it was severe; ‘a brute in human shape’. This was a climactic comment on the actions of just a couple of local people, which reflected badly on the whole community and caused eternal regret. It is often the case, that regrettable actions by just a few will sometimes overshadow greater and more noble acts. On that day, and during the days and weeks that followed, a considerable number of victims and personal items were recovered by local inhabitants. These acts, and the reverence shown to the victims, can only be been as admirable.

It seems clear that, there were few on the deck of the Pomona, when she ship finally sank. Those that got away, were by and large, crew and some cabin passengers. Helped by the ongoing work of the salvage divers, when the ship began to break open, the bodies flowed out of her. The victims who were not recovered during the immediate aftermath of the tragedy, were picked up along the whole of the east and south coast of Ireland during the months to follow.

It was reported that 7,000 emigrants had already travelled that season, and the loss at Blackwater, represented five and a half percent of them.

It was common for confusion to present in tallies, after the loss of an emigrant vessel. Record keeping in this respect, was seldom accurate, and overselling accommodation was common, as were stowaways. This case was no exception. Once again, many newspapers just reprinted what had gone before in others.

The Liverpool Mercury May 3, 1859, published an account of the disaster, and a passenger list (Below). They also listed the names of the survivors; 3 passengers and 20 crew. One of the surviving crew, was named, John Meehan – passenger’s cook. James Mulcahy, also reported to have been the ‘ship’s cook’, was not listed there.

List of Passengers

‘The Pomona had on board when she left Liverpool 393 passengers, namely, 16 married males and 26 married females, 148 single males and 164 single females, 32 children between the ages of 1 and 12, and 7 infants. The following are the names.’

When one totals the number passengers, 393, with the reported number of crew on the Pomona, 44, the figure amounts to 437.

The enquiry held by Arthur Walker JP, John Walker JP., and the nautical assessor for the BOT, Captain Harris, at Wexford, May 7-9, delivered the totals; 400 emigrants, 44 crew and 4 others. (Stowaways?)

The undisputed figure of 24 survivors puts the total number of victims at, 424. The discrepancies in themselves are not large, but where there is confusion, doubt will remain.

The ‘List’ continued, and included a full roll of passengers. [For further reference – Some publications carried detailed lists of passengers.]

Despite it been the worst emigrant shipwreck disaster seen on the coast of Ireland, and all the hullabaloo it created in the county of Wexford with, depositions, inquests, BOT enquiry, extensive salvage, shock and horror at the all the bodies washing ashore and accusations of their mistreatment, members of Wexford County Council and the Wexford Harbour commissioners, made no reference to it in their minutes. It was an incredible event in many ways, but it did not create an obstruction to the harbour. There was nevertheless an issue concerning the ‘lights’ within their jurisdiction, and a common sympathy maybe? But it just didn’t come up for mention at official County level.

Harbour Commissioners minutes read as if they had been exclusively preoccupied in the day to day running of the harbour, pilots’ expenses, the obsession with charges for ballast and their evasion, and so on. Neither was there a mention of any donation made to the lifeboat, or for the burial of the victims. I am sure that it was not the case, but it appears from the ledgers, that they just hoped all mention of the disaster would go away.

Locating and Diving to the Wreck of the Pomona

Wreck Hunting and the Law

As I have already admitted, our small band of diving enthusiasts can only be described as ‘wreck hunters’. Despite the fact that this description has both popular and disreputable connotations, we do not search for forgotten shipwrecks willy-nilly, or for brass mementos, or for profit. We chase lost and forgotten history, and ‘The Story’.

These days, our hunting is determined by a number of factors. Given that, all of our group, bar one, I being retired from the nasty habit, have to work for a living, being just one of them. It is therefore, a part time hobby. Our activities are also regulated by the vagaries of the weather, available finance, and the laws of the land. Much as we would love to have a Ballard or Odyssey-like budget, ours remains a comparative ‘shoe string’ – child size.

Given our age profile, the type of diving that can be comfortably accomplished now, is well below the fifty metre range. This keeps us by and large, in the more shallow inshore areas, and gaining ground on the ‘bus pass’. What we have going for us, is well grounded enthusiasm, an intelligent approach to research and survey work, and a deep interest in maritime history.

The notion of hunting for shipwrecks seems exciting, and in practise, it is. However, the practise is restricted by legislation, most of which is welcome. The implementation and tailoring of it, suffers from attitudes, and the where-with-all of professional archaeologists, who are constrained by ever diminishing departmental budgets. There are few votes in archaeology, which makes it difficult to compete for a share of the national cake – taxpayers’ money. It has become less troublesome to adopt the position that; if something cannot be searched for, recovered and or preserved according to ‘best practise’, then it is best left where it is.

The laws in Ireland differ considerably with our nearest neighbours in the UK, and the difference continues to be a source of heated discussion and argument, between those active in these jurisdictions.

The legitimate view taken by the professionals is that, when artefacts are removed from the seabed without record, the scene of a shipwreck, their context is lost forever. This is undoubtedly true. The alternative, which is also true, but denounced, is that a shipwreck will continue to decay and crumble in its underwater environment, until its contextual value is almost completely obliterated. It is also true that, the contextual value of the varying aspects of a ship’s construction, and the artefacts associated with it, may have already in some cases, been de contextualised by the original violence of the wrecking; such as a torpedo, reef of rocks, or by years of abrasion, trawling and previous professional salvage. There is also the argument, which is centred on the ‘age’ of a wreck, and the archaeological value that might be retrieved from shipwrecks, of say the Victorian period, and thereafter – questionable? Some ships, shipbuilding, and the maritime commerce of this period and later, is so well preserved and documented in many cases, that preservation for preservation sake, may be unwarranted.

To my mind, discovery now is better than the uncertainty of no discovery – maybe ever. There are no waves of criticism breaking over the operations of Odyssey Marine for instance. The USA seems to handle any amount of historical discoveries quite efficiently. Is it just a question of money?

How it works in Ireland at present, is as follows. The over-arching ‘100 year old rule’ means that, any shipwreck – not the age of the ship, that is one hundred years old, is protected, and a licence must be obtained, if you wish to dive to it. Chronological exceptions are made in the case of certain vessels, such as the Lusitania and the WW1 German submarine, UC42, both wrecked off Cork, which were deemed to warrant an exclusion or protection order, for reasons the statutory authorities decided. My own ‘golden rule’ is that, what was lost was owned – by someone.

Divers and researchers like our own little group, or even a diving club, will first identify a shipwreck of interest. We then apply for a licence to use detection equipment to search for it. Having found something, we must then apply for a licence to dive and look at it. In order to identify or age the wreck, we might recover a piece of pottery or something else than can be dated – this too needs a separate licence, and if it’s done without permission, you must explain why. These licences may then be granted, on an annual basis.

Any intention to excavate the wreck – well you can whistle that one. This requires a considerable amount of consultation with the authorities, and a pile of paper work, and can also be prohibitively expensive. Discouraged from retrieving artefacts, any that do break the surface, for one reason or another, must be handed over to the appropriate authorities.

In other words, you may, after a very lengthy an expensive process, have discovered a very important shipwreck and artefacts, which entitles you to nothing. The position of professional archaeologists is understandable, and often final. However, a balance in everything is desirable, and can often be progressive and rewarding.

Notwithstanding all of the above, I understand that the underwater archaeological unit attached to the department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, is chronically understaffed, and under financed. Despite this, our own small group has been fortunate to have received excellent advice and guidance, from this unit. I would nevertheless, feel comfortable arguing that, more should be done to encourage certain types of amateur wreck hunting. When found and recorded, considerable leeway should be given to the mapping and recovery of some artefacts from some shipwrecks, for local display. Finding suitable areas of display, may of course present some difficulty, but not insurmountable.

—

Beachcombers or Wreckers?

‘Each tradesman smuggled or dealt in smuggled goods; each public-house was supported by smugglers… each country gentleman…dabbled a little in the interesting traffic; almost every magistrate shared in the proceeds or partook of the commodities.’

G.P.R. James.

It was 2013, and spirits were flagging. Our search for the Count de Belgioioso (1783) had barbed us for years. Almost all the areas of interest had been explored, and we were were finally coming to the cloudy end of the barrel. Despite an unwillingness to submit, it was time to start considering a new target. Preferably, it should be one of historic interest, in easy reach, and a shipwreck that had not been previously discovered.

A notice inviting tenders, for the salvage of the wreck of the Pomona, was posted, and salvors from Liverpool arrived at the site of the shipwreck, surprisingly quickly – within a fortnight of it going down. The men were led by the diver, Richard Blower, and according to a statement made by him; he arrived at the wreck ‘on board a steamer sent by the United States Steamboat Company to look after the wreck of the Pomona.’ Blower was an experienced and well able diver, and was assisted by Joseph Rodrigeaux. They travelled from Liverpool to the wreck by tug, carrying all their diving apparatus and towing two barges.

[Whilst the manager of the dive operations was said to have been Blower, it was also reported that the head diver was John Allen, a diver based in Liverpool, and performing various salvage work around Great Britain and Ireland. He contributed to the Pomona distress fund at Wexford.]