‘The Most Abandoned Villains of Wexford’

Some say it’s the deep sounding whoosh from the revolving blades of the enormous turbines at Carnsore Point, in county Wexford. But when they rest, others will offer; it’s the confusion of winds that can blow around this large expanse of low lands, a place of prolonged periods of light, where two seas, the Atlantic and the Irish Sea, meet. Others, those who have been blessed with a tradition of folklore, will tell you, that energy of sound is never lost and that it is the echoes of so many whaling emigrants who lost their lives along the coast of Wexford, seeking life and fleeing starvation.

The two images show rescue from shipwreck by lifeboat and fishing boats. In such cases the crews were sometimes the same men or from the same extended families – local fishermen. And it’s still like that.

Although gorged, the Famine’s grim reaper did not rest after his climax in the 1840’s, but after he had called so many from the land of Ireland, he did begin to lose his appetite. The population still starved, and too many still found it impossible to do more than just exist. The emigration trail bulged, and no more so than than on the passage from Liverpool to America.

Steam was beginning to catch up on sail, but American shipbuilders seized the opportunities presented in the increasing demand for their lumber, foodstuffs, and cotton in particular. The days of the clipper sailing ships had already arrived, and America began to build bigger and better ships in faster times. They shipped valuable cargo to England and Ireland, and returned with the valuable humans to America. Humans were indeed valuable, as they were still being bought and sold in the South Americas. It was a highly lucrative two way trade for a number of years; a time of a financial model we now call a, win win.

The route was well known – Liverpool to New York. Embark at Liverpool, sail out to The Skerries off the northwest coast of Wales, turn left, head SSW down the Irish Channel, turn right at the Tuskar, and then it’s just plain sailing, westward for America – couldn’t be easier. Do it with your eyes closed – and I am afraid many might well have.

The wobble would occur when the easterly or south southeast winds were stronger than expected, and a ship’s captain failed to allowed sufficient offset for his drift westward. The calamitous result that so often occurred after misjudging the inadequate navigational lights on the dangerous shoals off the east coast of Wicklow and Wexford, simply put, was; ships’ course were altered westward prematurely.

The Banks are riddled with numerous shallows and although some were lucky, far too often the packed emigrant ships just ploughed into them with disastrous loss of life. Thanks to the marvellous surveys produced by INFOMAR and DUCHAS, the remains of many have been located and recorded.

The enquiries that invariably followed, unearthed numerous reasons for errors. These included the quite justifiable accusation of; inadequate and insufficient lights, lightships, buoys and lighthouses. In almost all cases, the compass was blamed. Difficult to prove when a compass is at the bottom of the sea, the phenomenon of compasses being affected by large amounts of iron cargo was nevertheless well known. The perennial, ‘sounding the lead’, or not, was another item at the top of list in the enquirers almanac. The quality, sobriety, and actions of the crew, even some passengers, were also to blame, and so on. The ship’s certificate of seaworthiness, or any other reports of its general condition, was also at the top of the list.

By the middle of the 19th century, enquiry proceedings that followed a shipwreck incident, began to take on routine pattern of formality; the industry was becoming better regulated. The principal instigators, upholders of these proceedings, men whose word carried some weight, were the coastguards, Revenue staff, local land owners, and Lloyds agents. The crew and even the captain’s word, was often viewed with suspicion. In cases, local parish priests intervened on behalf of their flock often accused of looting or ‘wrecking’. These were early days of the Board of Trade and Merchant Shipping regulations, and the formalities were not always nor uniformly applied around the coast.

One, or ‘anoraks’ like myself, are always on the lookout for the unusual in accounts of shipwreck incidents. It may only take a small remark, or the lack of remark, something that just doesn’t seem right. And certainly, any reference to the much maligned ‘wrecker’, always catches my interest. Knowing, that in the majority of cases, it’s use has cast that catch-all derogatory understanding over the character of local people, who may have lived at, and more often, from the sea for generations.

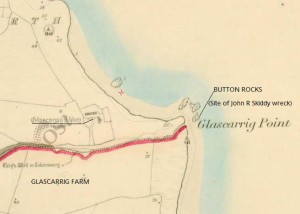

Built at the famous yard of Daniel McKay & Pickett, Boston, in 1844, the John R Skiddy, at almost a 1000 tons, set numerous records for cross Atlantic passage, and under her owner captain, William Skiddy, she consistently maintained highest averages. On March 28, 1850, her replacement commander, captain Shipley, took the packet ship with over 400 passengers and a mixed cargo into the Mersey channel. Having turned left at The Skerries, and down the Irish Channel he was on his way. True to form, captain Shipley later claimed, that he discovered on April 1 that, the SE winds had pushed him more sideways, westerly, than he had allowed for. That same night, mistaking the Arklow Bank light for the Tuskar light, he turned right – too soon. The ship does not seem to have struck anything, until, in ‘rain and thick weather’, it ran up on the Button Rocks, Glascarrig Point, near Cahore, county Wexford.

In terms of shipwreck, this one appears to have been quite a fortunate affair. It appears that the Skiddy did not ground with a great deal of violence, the scene described by the captain as ‘quiet’, and there was no loss of life. The ship did bulge on the rocks, but the water never rose over the upper deck. Although she came to rest close alongside Glascarrig beach, the captain and crew suspected at once that she would become a total loss.

An interesting aside to this story, arose with the description of her resting place. The ship was reported to have wrecked ‘under Glascarrig Monastry’. At first mistakenly believing this to be a nunnery at Cahore Point, it proved a bit of a mystery. On further research, this was a reference to the ruins of an ancient 12th century Benedictine Abbey or Priory that must still have presented some remains in the lane to Glascarrig Point. Obviously known about at the time, but now, its ruined walls are believed to have been incorporated into a later dwelling or and a cowshed nearby. The site is connected with the landing of St Patrick, as is the ancient monastic site adjacent, at Donaghmore.

(See Appendix for update.)

Old ordnance survey map showing the Abbey at Glascarrig, and site of the wreck of the John R Skiddy.

Glascarrig Point, with Roney Point and Tara Hill in the distance. The Button Rocks, site of the wreck John R Skiddy in the foreground. This sand dune is still known as ‘Skiddy Bank’.

Captain Shipley was sharp. He assessed his situation well, almost at once. The coastguards and local fishermen arrived on the site quite quickly, some being from the nearby fishing village of Cahore, less than a mile southwards, and others from the small harbour town of Courtown, a few miles northwards. Shipley new he must stay with the wreck and assert his owners authority in protecting the value of the hull and its cargo, at least until the authorities, or the Lloyds agent arrived.

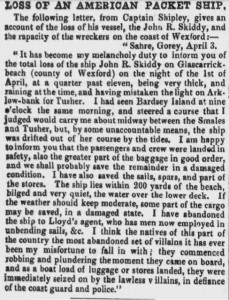

He lost no time getting one letter off to the owners and agents, Spooner Sands & Co. in Liverpool, and another to the newspapers. His letter to the Press was a damning criticism of the local people, including the Coastguard, as to the inhumane treatment they received at the site of the wreck. It was probably printed in every newspaper in the world – with maybe only a slight exaggeration. The letter to the agents was more detailed and it too was reprinted everywhere.

Captain Shipley’s derogatory remarks; …“I think the natives of this part of the country the most abandoned set of villains to have ever been my misfortune to fall in with:..” certainly livened things up, and would eventually have to be retracted.

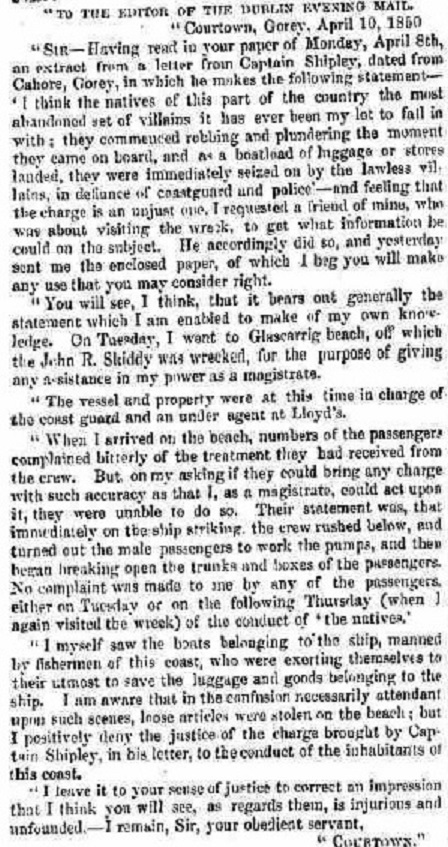

Shipley’s first letter.

Who and what he was referring to, were those who had boarded the ship, coastguards and locals, and supposedly roughly handled the crew and passengers, women and children, while stealing valuables from their belongings, without and within the wreck.

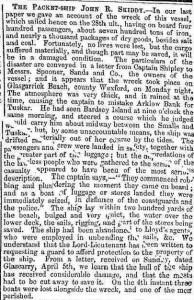

Shipley’s letter to the agents and owners, shown here, was considered slanderous by Lord Courtown, and was reprinted everywhere!

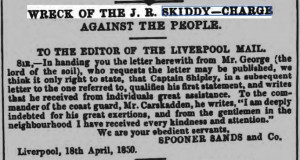

Allegations repeated.

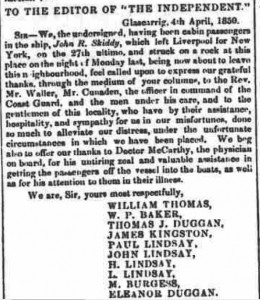

After testimonials to the contrary from the passengers themselves, the local manor estate occupant, Earl of Courtown, and other prominent members of the community had weighed in, Captain Shipley was forced to moderate his accusations, albeit grudgingly. The culprits had been his own crew, and were later the subject of investigation and enquiry at Liverpool.

Letter of thanks from passengers to the Press.

Tapscott, the shipping agents, given the furore and potential for ‘bad press’, proudly boasted they would allow the survivors to reconvene their voyage to America on another outgoing vessel, ‘free of charge’ – if they presented themselves at Liverpool with some proof of the previously booked passage. Failing to mention that, they had not completed their own contract to transport the wretched shipwrecked victims to America in the first instance. Personal compensation on such occasions, in the manner we enjoy today, would have been unheard of. Free lunches were equally as scarce then.

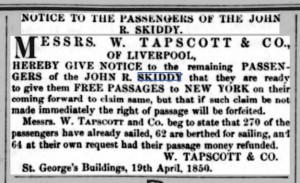

Tapscotts offer of ‘free passage’.

Lord Courtown’s letter clearly outlined the damage that had been done in the past in such cases – ‘tarring everyone one with the same ‘wrecker’ brush’. It completes a picture of the scene at the wreck site, with an account of a more balanced and accurate nature. Although not as widely published as captain Shipley’s letter, it achieved its purpose. And for everlasting clarity, it is reprinted here.

And then Captain Shipley’s qualified retraction.

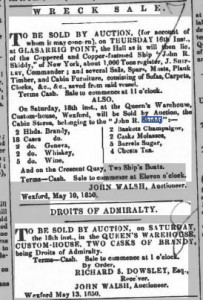

The wreck was dismantled on site. Some of its more valuable parts and cargo were shipped to Liverpool and auctioned there. The remaining wreck items were the subject of auctions on site, over several months. The local auctioneer, Walsh, who must have salivated at the sight of a good storm, seemingly having had the ‘Wreck Auction’ business in the county wrapped up, pretty much.

Wreck auction notice.

It is said that some of the ship’s timbers were used in the construction of buildings on Glascarrig farm, and it was remembered to me by local people, who recall being told about the rafters in the old house there; ‘ah yes, pitch pine, there from the ‘John R’’.

View of Glascarrig Point and Tara Hill from the Strand Bar,Cahore. (Also known to some as The Harbour Bar)

Lord Courtown’s letter was joined by others from serious civic heavyweights, and it was not so much there letters of support for the coastguards and local people, as reference to the commander of the coastguards in question – Carskadden. An unusual name and one that, not so much the spelling, but the sound of, that rang a little bell. That odd little occurrence I mentioned.

In 1975, the renowned maritime historian, Dr John De Courcy Ireland, published the timely and well received book, Wreck and Rescue. In it he refers to the loss of the John R Skiddy and the sometimes ambiguous role of the coastguards – ‘sometimes sliding into viciousness’.

He was referring in particular to the following words in the old Wexford ballad:

‘The curse upon Crossgadden, likewise his robbing crew,

They robbed the Irrawaddy and the John R. Skiddy too.’

The reader will immediately see the likeness between the two spellings for someone who is obviously the same coastguard of the period.

The Irrawaddy, another large emigrant vessel, and as luck would have it, it too not occurring any loss of life after it struck the Blackwater Bank in 1856. It was abandoned and boarded by local fishermen, followed by the coastguards, before it drifted off the Bank and onto the beach at Cahore Point. Crossgadden, described as a big man, this incident was a robust affair, and again, the same accusations rang out. Several fishermen from Arklow and Courtown were taken into custody and sent for trial – but not the coastguard.

After a number of testimonies, and intervention by the local parish priest, Father Redmond, all the men were found innocent. But a sum of £1700 was sought by the owners of the ship for the loss of cargo, valuables etc., and were insistent, that under some obscure law, a levy be put put on the county of Wexford for the amount – the judge agreed.

It was a sore point, and the adjudication was bounced back after councillors pointed out, that most of the men involved, Arklow men, were from county Wicklow.

Seats in Ballygarret church, constructed of timber from the wreck of the Irrawaddy.

Fishermen had been saving men, ships, and cargo, at the risk of their own lives for centuries, and had been receiving nothing, or mere trifling amounts for their trouble. This case and other later ones left a bad taste and a struggle for fair treatment between the ‘wreckers’ and the authorities continued.

Getting back to our ‘chief of the coastguards’ man. It was true that Cuscadden, William, was present at the Irrawaddy event, he also attended the dreadful loss of life in the Pomona incident at Blackwater in 1859, and probably many more, but Lord Courtown or the journalist had misspelt his name – albeit with an alternative spelling used in Donegal. After some frustrating checking, I discovered his name spelt in several ways; Cuscadden, Crossgadden, Carskadden, and Cunaden by some passengers – Cuscadden used more often, but more correct is Cuscaden.

Dr de Courcy sites J. Ranson for the information on Crossgadden. Reverend Joseph Ranson CC, a member of the RIHS, had collected a number of songs, ballads and music that told of shipwrecks along the coast of Wexford. It was printed in 1948, and reprinted by James Hammel jnr., & others, in 1975. In it, Father Ranson recalls collecting some brief words of a lost ballad(s), The Irrawaddy and The J.R.Skiddy, from Margaret Mitten, buried in the same Donaghmore, mentioned earlier. The words are identical to those in, Wreck and Rescue, and give the coastguard’s name as, Crossgadden.

But there were never any charges brought against this man, he and his men even received a commendation and financial reward from the Royal Lifeboat Institution, for their rescue of the crew of the wrecked schooner, Pearl, at the same Glascarrig Rocks, in April 1858. And although you might read between the lines in some accounts of the Irrawaddy, and be tempted to come away with some suspicion of wrong doing; this however is just the same as was done to the local ‘wreckers’ by captain Thomas Shipley.

Reports indicate that William Cuscaden was attached to the revenue cruiser Prince Albert and was civil second mate of the coastguard Eliza based at Westport in 1843, and promoted to its commander in 1846. He appears to have moved to Cahore, Wexford shortly after that. The antipathy some local people might seem to have harboured towards Cuscaden, might have had more to do with his Scotch/Irish protestant roots, and the fact he was a member of the Masons. So, maybe we too have done some service for the Cuscadens.

Several months after the John R Skiddy incident, the following notice appeared in newspapers.

This notice makes clear that there was some stealing of property from wrecks in the area. Whether nails or flour, Father Redmond had good standing in the community, and he was determined to protect his own, and the reputation of his parishioners. What is not made clear is that, the items ‘stolen’ were often perishables, and liquor, and could not be returned.

The Calypso wrecked on Mizen Head, Wicklow, in February 1838. After the coastguards reached the wreck, they were attacked by the ship’s crew in an incident that is unclear. Cuscaden was not involved. The cargo that washed ashore was reported to have been plundered by local people, after which ‘thousands’ descended on the scene. The coastguards were later rewarded for saving the cargo.

In the case of the Hottingeur, just a couple of months prior to the John R Skiddy, she struck the Blackwater Bank and sunk afterwards, on the Glassgorman Bank, with twenty drowned. She too was reported to have been boarded by local fishing boats, and looted, before the coastguards could intervene.

Armies of various shades had trampled over Ireland and stole its lands to bequeath, one to another. Her population was religiously persecuted and subdued into penury and starvation. The Skiddy incident occurred in 1850, newspapers continued to report deaths from starvation around Ireland, and did so for many more years thereafter. Women were transported for stealing a handkerchief, and men could be hanged for ‘looting’ a wreck.

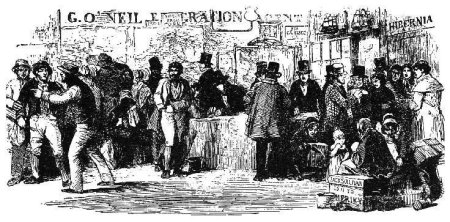

A depiction of a scene outside Gregory O’Neill’s emigration office in Cork.

Emigration agents were shrouded in criticism of terrible behaviour at the time. Mr. O’Neill, was well respected in Cork, and appears to have been an exception. The name O’Neill was strongly associated with emigration to Quebec, and remains well known in emigration law today.

At year’s end, a list of salvage amounts claimed by the coastguards under ‘Droits of Admiralty’ was published. The shipwreck instances at Wexford, included a sum of £501, which was paid in the case of the John R Skiddy. The Hottingeur and the Calypso were not mentioned.

Captain Shipley took command of another new American packet ship soon afterwards, called the ‘Underwriter’.

William Cuscaden (retired coastguard), is shown in the Wexford directory 1885, at the house, ‘Alexandria’, which may be the old house in the same area, known as ‘Alexandra’, in the north suburbs of Wexford town. Chief coastguard, Captain William Cuscadden (1801-1887), was buried overlooking the scene of his toil, in Ballyvalloo cemetery, a little south of Cahore, county Wexford, in 1887. It is documented that he had eight children by his two wives and that two died prematurely. With some confusion, the remaining sons and daughters would seem to have emigrated to New Worlds.

His son William Andrew, born in 1853, studied at Trinity College Dublin, and played rugby for Ireland. He travelled to the Far East as a high ranking officer in the police force.

William Henry Cuscaden died leaving modest means. Addressed at, The Folly, Wexford, he lies buried with his two wives, sharing a remote coastal burial place with a number of shipwreck victims he was unable to rescue. It is a testimony to the great number of lives that were lost to shipwreck along the coastline of this county that, he could have been buried in any cemetery in sight of the sea, from Wicklow to Wexford, and shared similar company.

Ballyvalloo cemetery, co., Wexford.

William Henry Cuscaden’s damaged headstone reads; ‘Gone to be with Christ which is far better’.

Appendix.

During a recent visit to Glascarrig, 2/7/2021, I had the good fortune to meet a local person as he strolled along the shore. I was stopping the night in a campervan and we got chatting. He informed me that the dune against which I was parked only yards from the water’s edge and from where I had taken the earlier photograph, was known as the Skiddy Bank. The inference is obvious.

The large mound nearby (Locally called the ‘Moate’ known by experts as the Motte & Bailey.)is circled by a ditch and was said to have possibly been a very early fort and part of an ancient settlement. To this gentlemen’s and my own eyes, it look like a Viking burial mound. Having seen many them in Norway there seems little difference.

In any event, it is a great pity such sites as this, so many around the country are not thoroughly investigated in order to examine and discover our history. I daresay if local authorities could fund these projects any results would help to promote interested visitors to the area – forever. The edge of the site is being eroded and in real danger of been damaged or lost.

Author’s recent photograph.

Author’s image of semi hardwood pole at Galscarrig – possibly remains of a ship’s mast.

Thanks to:

Local people around Glascarrig and Cahore.

‘Find a Grave.com’

‘The Silver Bowl.com’

Wreck & Rescue by Dr De Courcy Ireland, RIP.

Songs of Wexford by Rev Jospeh Ranson CC & James Hammel Jnr.

British Newspaper Library.

‘The Scots/Irish Descendants of Daniel Kirk Born 1733 Scotland.’ By Catherine Varnum Johnson.

PLEASE NOTE:- All images, text and video contained in this post, can not be reproduced without permission of the authors or accredited artists.