Ostendse Compagnie

The ongoing research and hunt for the remains of the ship ‘Count de Belgioioso’ is fascinating story on many levels. And more, it has been an exciting journey. As much as I would love to recount the whole story here, one that would deservingly fill many pages, it is therefore much too lengthy for this forum – and sure then I have to shoot you. I will however, reveal some of the exciting facts that have been unearthed, after more than ten years of research and combing the seabed for the remains of this ship off the coast of Dublin.

Where to begin, ah yes, the setting. Slavery was big business, Britain was just closing the war with America, and all kinds of new ideas were being teased out by ‘philosophers’. The diving bell, ballooning, electricity, steam engines and their application in transport and industry. It was a period when there was a virtual revolution of ideas that would ‘improve’ the lot of humanity.

Eminent and progressive thinkers were in the ascendancy and excitedly corresponding ideas from far flung corners of the earth through a surprisingly efficient ‘postal’ system.

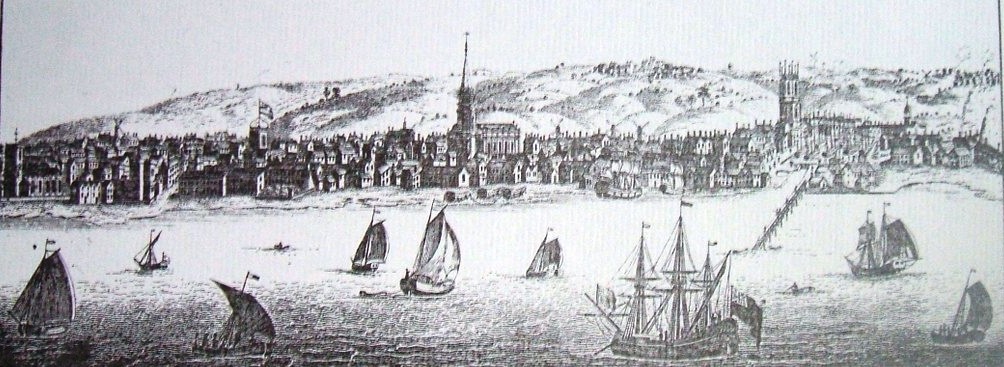

The Dublin Chamber of Commerce was about to be established, as was the Bank of Ireland, and Gandon’s Custom House masterpiece was almost complete. It was the 1780’s, sailing ships came up the River Liffey to Capel Street, the commercial centre of Dublin, where sailors could hop off and buy a lotto – and you think I’m kiddin.

A port which might be described as a sister of Dublin, Liverpool was the centre of the universe for many of its well healed merchants. These were men who had amassed incredible fortunes in shipbuilding, shipping, slavery and privateering – a respectable title sometimes given to piracy, legitimised by ‘letters of marque’. This was not unusual at the time, the ‘letter’ being permission from the State to attack its enemies at sea and seize their ships and cargoes. This licensing system was a great money spinner and one that was considerably abused. Being a shipping merchant then, was often the equivalent to having, in the words of a group of much later Liverpudlians – a ticket to ride. Believe it or not, many of these men moved into banking – piracy you say.

You might be tempted to think that shipwrights earned a crust by simply building ships and that was that. Not quite so, shipyards, wet docks, dry docks and even ‘slips’ in Liverpool, were of limited availability and jealously controlled. So, those in the know got the space, built the boats, and these were quite often used to ship their own goods.

This of course is not to say, that there was no room for lesser mortals, but they had to fight hard against the odds in order to stand shoulder to shoulder with the bigger mortals.

The ‘Belgioioso’ was laid down at Liverpool in 1780 by Edward Jolly and Co. A shipwright himself, but apparently a front for a business syndicate who launched the ship in September 1782. She was reported and considered to be the first East Indiaman built in Liverpool and despite being unable to unearth any collaborating paperwork, she was reported to have been ‘turned down’ by the English East Company (EIC).

A business practice by shipbuilders at the time, was to treat the construction of each ship as a separate investment adventure. A shipbuilder might throw in with investors to build a ship, and when completed, it was sold and the profits divided. If at any point before completion, the project was abandoned, it suffered dissection by that financial instrument called bankruptcy. Accounts were then settled from subsequent sales and auctioning of the available remaining assets. At this juncture, a ‘third party’ could secure an ‘almost completed’ vessel at a knock down price! The shipbuilder was then free to commence another project with new investors and so on. Your thoughts and exclamations are deafening, I know, some things don’t change.

Despite years of research, it is difficult, even today, to understand this next part of the story. I must first begin by explaining a little about what I understand an East India Company to have been.

It is not at all surprising that the clergy, in the form of the Jesuits, were first to get their feet under the table in the Far East. It was a time when this part of the earth presented almost limitless trading opportunities from all manner of high value merchandise, precious metals and gemstones etc. In the footsteps of the Jesuits, Portugal and Denmark I believe followed, and preceded most of their followers by a significant period. India also offered valuable opportunities, and acted as half-way house for further trade-on, to and from China.

These opportunities were so vast, that governments would not allow ‘lesser mortals’ to free trade, and introduced strict licensing systems. Trading companies were established by many nationalities, and among them, was the famous Honourable East India Company based in London.

A key to exploiting the new world was ships. These had to be sufficiently stout for the long perilous journey, large enough to carry the new ‘super’ cargoes and thus compelled to carry a generous compliment of armament and crew. The London East India Company became world leaders in this class of super cargoes, and the Crown benefited no end from the trade – enter the taxman.

It’s not easy to make this short but I’ll push on. A complicated history surrounds a company that was based in Trieste; this was the Imperial Asiatic Company (IACT). Earlier named, the Ostend Company. This failed but was re established in the latter half of the 18th century and licensed by the Hapsburg Monarchy to trade with India and China. It commissioned the construction of a number of ships for the trade and purchased others. Amongst the latter, two were obtained in England. This was ‘Count de Belgioioso’ built at Liverpool and the ‘Count de Zinzendorf’, which was the ex. English East Indiaman, ‘Duke of Grafton’.

The Grafton represented a practice existing at the time – when an East Indiaman ceased service with the EIC after four or five round trips to the Far East, and were then sold on after their best years. In the case of the ‘Grafton’, this was followed by an extensive refit.

You would be forgiven for asking, why would Britain assist his Imperial Majesty’s trading opportunities with the East, in direct competition with its own East India Co? And your misgivings would be well placed, as this is where the plot thickens. Although a petition was lodged in London on behalf of his Imperial Majesty and IACT, for permission to purchase the two vessels for the China trade, the co-owner of the ship(s?) was recorded as being a syndicate of merchants represented by a well known London based merchant with shipbuilding and family connections in Liverpool. Lloyds Register records ownership of the ‘Count de Belgioioso’ as ‘London’ and the ‘Zinzendorf’ as Germany.

There is also a historical suggestion that IACT actually relinquished their part ownership in these vessels in favour of larger ships, which they had on the stocks in Europe.

So, as the London merchants might not have been able to trade directly with the Far East themselves, i.e. without licence and in open competition with its own East India Co., through a convoluted scam, they arranged for what can only be called a ‘flag of convenience’. I know, ‘sounds familiar’. But who did they partner, if not IACT itself? This, I’m afraid, is another story, knowledge of which would also be punishable by shooting!

Meanwhile in Liverpool, the ‘Belgioioso’ had undergone final fitting, crew were hired and her large holds packed with goodies. The cargo consisted of a large amount of lead, 350 tons to be precise, used for all manner of purposes, shot, linings for caddies holding teas, spices, weathering etc. And, a large amount of silver in species and ingots, which was reported to have been more valuable than gold at the time. Baled goods, a consignment of valuable clocks by a well known London maker, and a large quantity of the valuable root, ginseng.

You might twig, and you would be correct, that this plant was already available in China? Ah yes, but it was so sought after there, that they couldn’t get enough of it. And although this consignment probably originated in America, where it was grown at the time, an enormous profit would be turned on it in China. Interestingly, this root was, and maybe still is, attributed with the same qualities as our modern day Viagra, which I suppose you could say, also turns a bob or two.

The Belgioioso is recorded as being 750 tons in Lloyds Register but 840 tons by IACT. There were a number of different methods of measuring a vessel’s tonnage but by whatever method or standard, this was a very large and stoutly built ship. She was armed with 28 guns and was probably modelled on some of the frigates built in Liverpool for HM navy at that time. She had three decks and her bottom was coppered, pushing her into the Lloyd’s classification, A1.

The crew might have been difficult to recruit, due to demand at that time, and we know almost nothing about them. The ship’s commander was Belgium or Austrian , Charles de Coninck, and its master was Pierce (occasionally spelt differently), probably an Englishman.

Unclear whether or not he was the ship’s surgeon or employed by the HEIC, probably an Englishman, John Archbald was aboard. The total number of persons on board was 147, which you might expect to be made up of about 100 crew and the remainder, passengers. The original petition however, stated that there were only twelve passengers, three of which were ladies of ‘noble birth’. The only passenger we have some detail was, Thomas Hutton, a surgeon with HEIC, on his way to Canton. It is indeed unfortunate that at the time of writing at least, we were unable to learn anymore about these people, which, given the extent of our searches, is unusual in itself, and we are sadly left with being only able to report, that none were ever heard from again.

The ship, built by Englishmen, owned by Englishmen, insured by Englishmen and stuffed with Englishmen’s goods, set sail for China, flying an Imperial German flag.

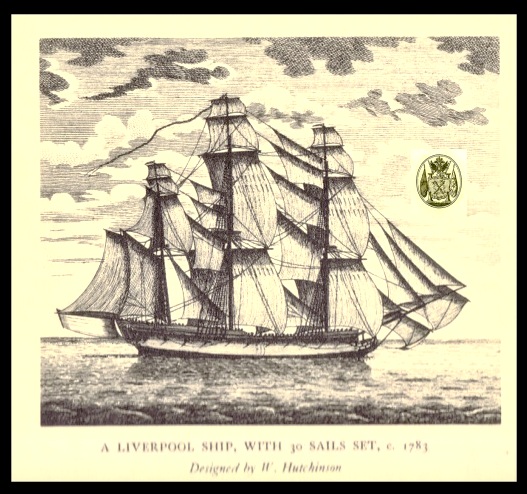

The weather had been terrible and delayed the departure of the ‘Belgioioso’. Liverpool had been beset by prolonged snow, severe frost and strong winds from the north and the east. Forecasting weather was not an accurate science then, but based on trends and the barometer. Notwithstanding, the dock master at Liverpool, the well known William Hutchinson, a privateer of no small importance in an earlier life, and a truly fastidious individual, was to be relied on. He was a keen ‘philosopher’ and kept a daily record of tide, wind and weather conditions for many years at Liverpool, and offered Commander Coninck the opinion, that the weather would come good on March 4. It was to be a good day sunshine, and would enable the bulging ship to get away.

He was proved correct, and the morning of Tuesday the 4th., was sunny and crisp, heralding a ‘great to be alive’ day. In advance of a falling tide, expected to turn around midday, the ‘Belgioioso’ let loose her thick hawser from the wall at the South Dock, and assisted by a favourable wind from the east and the benefit of a tow, pushed on out into Liverpool Bay.

The improvement in the weather however was only a lull, a cruel feint by the Gods. During the day, the weather reverted to its previous foulness, and worsened right into the night. Pressure dropped and snow returned with an ever increasing wind from the east, veering south east and heralding a storm. What appears to have happened next was almost replicated seventy years later, when the large emigrant ship ‘Tayleur’ was lost in very similar circumstances. The big ship was last sighted off Anglesea during the day before she was blown across the Irish Sea in blinding conditions and driven onto the Kish Bank during the early hours of Wednesday morning.

Just for a moment, let’s try to envisage that night. No GPS, no accurate weather forecast, no radio, no visibility, a new compass that may have been compromised. Dead reckoning becoming almost impossible on the wracked vessel. The result – being unable to determine an any idea of where you where. There is also a suspicion that the rigging was not properly stretched, and might have suffered from the ‘on and off’ of the severe frost conditions that had prevailed.

The biting wind is stripping the canvas from the masts, and the freezing seas are washing over the decks. Ship’s timbers are shuddering and splintering with loud cracks, as the hull of the mighty vessel becomes impaled on one of the most treacherous parts of the Irish coast. It was surely a terrible scene but one which sailors often faced.

The ship was lost but masts were visible above the water for some time. The weather improved quite quickly thereafter, and local fishermen reported the wreck to the revenue surveyor at Dunleary. The man was Forward Rumley, and he was a member of a family that developed interesting history at Dunleary and with HM Customs in Ireland. He also proved himself somewhat of a thorn in the side of smugglers.

No bodies were recovered from the loss, but some of the cargo came ashore and more was recovered by local boats. (Two unidentified bodies came ashore during salvaging attempts later that summer. Nothing is known about them.)

Some bales of ginseng were recovered and were later treated by two Dublin chemists and auctioned with a little help from friends in London.

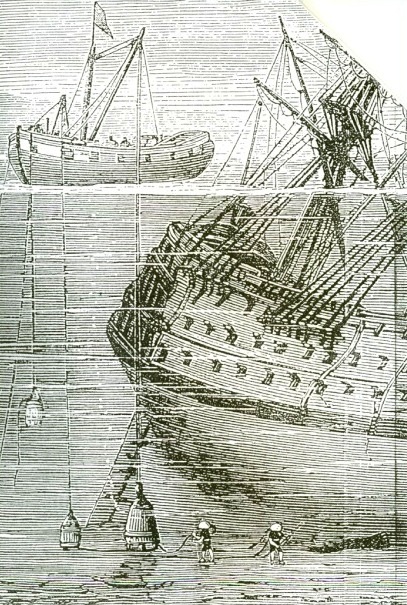

Armed with a very generous contract to salvage the valuable cargo, the insurers, ‘The Royal Exchange’, dispatched the notable bell diver, Charles Spalding of Edinburgh, for Dublin. There is much to be reported about Charles Spalding, his brother Thomas and his activities before and after the loss of the Belgioioso, their cooper-by-trade, helper and brother in law, James Small, and Spalding’s nephew, Ebeneezer Watson.

Regretfully, once more, we must desist for fear of the rampaging megabits. Suffice to say, during a well deserved rest from salvaging the ‘Royal George’ (see print), Charles and Ebeneezer arrived in Dublin in May/June 1783. After some exploratory dives to 4, and 7-8 fathoms, they were both hauled up on board the brig after the third descent and found dead inside the bell.

There was considerable interest and some controversy surrounding the mysterious and ‘melancholy accident’, and the ensuing inquest heard conflicting statements. Some accused the ship’s captain of negligence, and others blamed the rotten air produced by the ginseng or decaying bodies. Charles’s father was utterly distraught but clear-headed as to who was to blame. He accused the captain of not sending down replacement air to the bell in a timely fashion. The inquest concluded that Spalding and Watson had ‘not drowned’ and that their death was ‘accidental’. Their bodies were interred in the grounds of St Mark’s church in Westland Row where they remain to this day – or do they?

This is where the water muddies a little further. The insurers, who by this time were comprised of The Royal Exchange and private syndicates, both in Britain and Belgium, came to the assistance of the Spalding family. The Times announced the establishment of a distress fund by London merchants who were connected to the ownership and insurance of the ‘Belgioioso’. It was intended to relieve the suffering of Spalding’s grieving widow and her ‘seven infant children’, along with Watson’s mother. Donations were generous, and although Susan Spalding sold her husband’s confectionary business at Edinburgh, soon after his death, she seems to have fared well in the long run. It appears that the merchant managers of this fund were connected to the original purchase of the ‘Belgioioso’.

Now, they built it, they bought it, they shared it, they insured it and they attempted to salvage it! It strikes me that there was a lot of money, their own and others, sloshing around in the pockets of these ‘adventurers’, before the adventure ever left home waters. The salvage attempts continued through the summer and in subsequent years, up to 1787, when all reporting of further attempts ceased. Whatever was recovered from the ‘Belgioioso’, was either not up to much or remained a secret.

An entertaining curiosity for the general public at the time, not to mention myself, these earlier salvage attempts included the involvement of ‘Black men’, or ‘Africans’. While Spalding was in Dublin surveying the wreck, he befriended the travelling philosopher James Dinwiddie, a native of Edinburgh, who was not long arrived in Dublin. (The title ‘philosopher’ was a term used a little differently then, but generally speaking, applied to those experimenting with any of the sciences.)

Dinwiddie was a prodigious recorder, and became famous for his observations and experiments in mechanics, hydrostatics, electricity, navigation etc. And sure the man had opinions and suggestions on almost every topic under the sun, and was not shy with the ladies. More to the point, he went with Spalding to view the wreck and later suggested that he even descended with him in the diving bell.

Although shocked by Spalding’s death, Dinwiddie later ventured into the business of attempting to salvage the ‘Belgioioso’ for himself. Much to the curiosity of the inhabitants of Dublin, through his agent and fellow philosopher, Logan Henderson of 88 Capel Street, he hired a ship and a number of ‘Black’ people . These appear to have been an extended family and their ‘hangers on’. (‘Black men’ or ‘Africans’ were considered to be very good divers and had been very successfully employed by Spalding. Some of HM ships also employed them for the same reason ) Before his efforts got off the ground however, Dinwiddie had to leave Dublin in a hurry.

It appears that the man might have got himself into some financial difficulties, and it was a while before he returned to Ireland. Ballooning seemed to catch his interest at this time, but discovered his efforts to be in competition with those of a very familiar name about Dublin at the time, Crosbie. Notwithstanding, debts were accumulated by the ‘Black’ people who continued salvage attempts on Dinwiddie’s account, before finally legging it to Wales in the late Summer of 1783.

Some wonderful accounts of the activities of the ‘Black’ salvors appeared in the newspapers, lending an air of the theatrical to the serious business of recovering a fortune from the seabed. Their attempts were followed by others, with little success reported. The well known diving family, the Braithwaites, appeared in 1786/1787, expressing optimism for a successful salvage. It would appear however, that they were unable to obtain the contract, as it had already been awarded to a competing salvor. Nevertheless, they were the last to be mentioned in respect of any salvage attempts.

Others that followed may have been Charles Spalding’s brother, Thomas, with James Small. Although Thomas was a surgeon with the HEIC, he was very proficient with the diving bell and its advancements. (Did he lead the field, when he drew air with a pump into his bell at several fathoms from the surface in 1786?)

Barring the recovery of some anchors and rigging etc. there is no indication of serious success by any of the salvors. But if you look closely at the shop sign over the premises at number 88 Capel Street, today, you will observe some first class irony!!

I just knew I couldn’t make this short. Making a giant leap in excess of 200 years, we have a number of guys combing the bottom of the Kish Bank, in search of the elusive shipwreck. Keith Browne suckered me many years ago with the honey trap that is ‘Belgioioso’, and the rest as they say, is history.

Why is the wreck proving elusive? It was sticking up above the water for several months. Prospective salvors visited it for at least five years, local fishermen reported it, and of course the ‘piratical marauders from Bray and Wicklow’, also appear to have had a go at fishing up the treasure. The answer is this. Although the wreck was seen and written about, the written reports were very careful not to include a description of the position, except to state, the ‘Kish Bank’.

The difficulties experienced trying to locate this wreck do serve to illustrate how such an event can disappear from the consciousness of even local fishermen, confirming the immortal words of a soul mate, Clive Cussler, – ‘Time buries all memory of a location’.

Now, where or what is the Kish Bank?

To cut a long story short (sorry about that), a mention of this elongated submerged island of sand, the Kish Bank, positioned off the coast of Dublin and Wicklow, might have included, all or some of the following; The Kishes, The Kish, the North Kish, The Tail of the Kish, the Bray Bank, the Bray Swash and sometimes even the Ridge and Codling Banks. Leaving out the Ridge and Codling (for now), the remainder stretches for almost ten miles – forgetting the width. Where does one start?

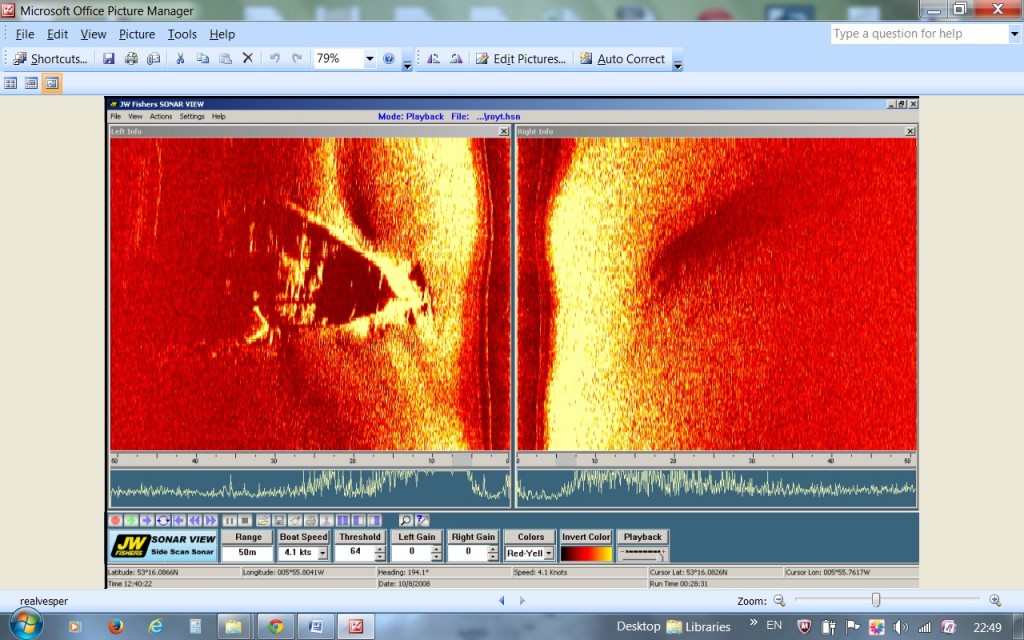

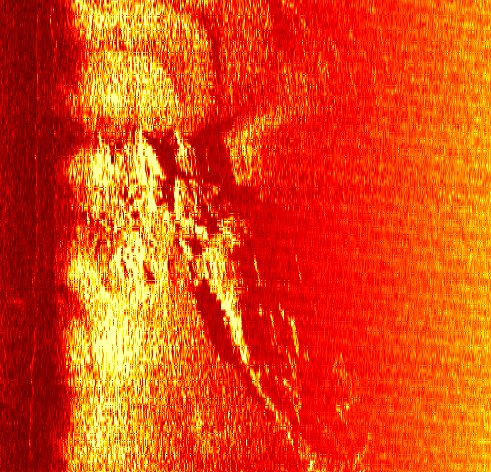

There were some tentative references that guided us in the direction of the Kish Bank proper, as we know it today. Using a side scan sonar and magnetometer we have covered all the possible areas here, and are now concentrating on the lower or Bray end and Codling areas. The bottom of the barrel, you might say.

We have in all, detected the remains of approx. 14 wrecks with no luck. This included iron and steel wrecks, wooden wrecks and a composite wreck. We looked at a number of iron cargoes of varying types, brass and vast quantities of pottery with no indication of been in the ballpark. We have applied for our licences annually and knew for certain, each year ‘had to be the year’, if only because the sand of time is slipping through the glass.

Why do we do it? I don’t know. It’s not because ‘its there’. It’s not, as many believe, the silver – its present day condition and value being dubious. Indeed a licence to look for a wreck is one thing, obtaining a licence to remove ‘artefacts’, is quite a different ‘kettle of fish’. It’s just one of those things. It gets into you, and you can’t let it go. Finding the first East Indiaman built in Liverpool would be nice but maybe it’s just the call of a Siren.

The ‘B Team’

(From left, Keith Browne, Chris O’Shea, Roy Stokes and Graham Stokes. Not to forget the generous and valuable assistance rendered by the Marlin and Aquarius diving clubs.) The boat’s name is ‘Thrupence’.

Not a short story but alas, too short, as I have had to leave out loads of juicy bits!

Roy Stokes, 2013

PLEASE NOTE:- All images, text and video contained in this post, can not be reproduced without permission of the authors or accredited artists.