The Atlantic Gateway (Jim Phelan 1941)

When ships crossed the channel between Ireland and England during WWI, they were attacked and sunk by German submarines. The loss of ships, Irish or not, with civilians, service men and women, was not only condemned by those considered to be ‘West Brits’, but anger and a sense of loss was felt by a large majority of Irish citizens – subjects of the British Crown.

They were accused of it, but generally, we didn’t blame Britain for putting Ireland in the way of German harm because of its war with that country – we blamed Germans. And Germans didn’t believe they were attacking some kind of ‘occupied neutral’ country off the west coast of Britain – they believed they were attacking Britain and British ships.

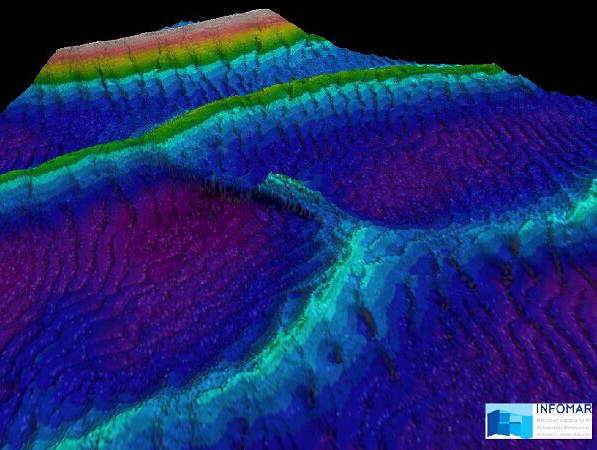

The channel between Ireland and England, described at the height of the U-boat campaign against Britain by some in the Admiralty and in Whitehall, as a ‘quiet lake’, was a blustering fit of pique. The war was not going well, and the real danger posed by a modern fleet of enemy submarines controlling the seas around Britain was advancing. Germany’s mass production techniques had carried over to building submarines and presented a growing threat.

The part Ireland was playing in the war was quiet simple, and similar to any of the industrial counties on mainland Britain. It was also more comprehensive than a half century of post WW1 history suggested. General commerce, war materials, food and volunteers – implementing conscription in Ireland was a thorny issue for the Crown, and was avoided. As we have learned since, there were plenty of volunteers and a terrible price was paid.

Ireland’s geography has always been interesting, and none less so today. Alongside Britain, it dominated access to northern Europe for centuries. Britain had shared control of the English Channel with France, and even without her at times, this meant that, during a time of war, northern Europe, the Baltics and Scandavian countries could be compelled to make an arduous voyage round northern Britain, in order to gain access to the north Atlantic. However, if Ireland had been allowed to become independent, and derived an independent and sympathetic foreign policy with enemies of Britain, (As it is wrongly attributed with during WW2.) events in Britain and Europe might have developed quiet differently.

Often forgotten, are the ancient trading connections between the west of Ireland and other Atlantic coasts of Western Europe, and right into the Mediterranean. This trade was carried on with little regard to any government controls.

The north and south coasts of Ireland were ideally located and suited to guard this strategic access to the Atlantic, and ultimately to and from the rest of the world. And although it is a different age of technology and communication now, it is nevertheless not surprising, that Britain still maintains a hankering for an unfettered control of the North Channell – an ocean gateway to its industrial heartland. The fact that control of Britain and Ireland is gradually being seeded and centered in the heartland and source of Europe’s historic conflicts, is an irony no one would have seen coming in 1917.

Progress of the War.

For a time, both the German and British High Seas fleets were bottled up. One in fear of the new German submarine menace and the other, compelled to use one or other of the ‘ocean gates’, might only expect ambush, going and coming.

When the implications of Britain losing the war or suing for some kind of subservient peace with Germany, became clear, America threw in with Britain. Not for the reason so often mentioned, ‘the sinking of the Lusitania’, but two years later, when the danger from a ‘new’ Europe became more obvious. A German dominated Europe with a combined battle fleet of unparalleled proportions, loose on the high seas, was not a desirable prospect. Little did the Americans know, they would have to perform a similar rescue twenty years later.

When America committed, it quickly established large military, naval and air bases across Britain and Ireland. The bases were extensive, including those at the geographical sentinels in the north and south of Ireland. Acutely aware of America’s industrial capacity, German strategy at this time was to throw as much resources as possible into the war, in order to force surrender or peace, before the Americans could make a difference.

Just like in any of Britain’s counties, transport, one of Britain’s great strengths, needed to be maintained, in order for commerce to thrive, and war material to be transported. So too, it was with Ireland. Its connection with Britain had to be maintained at all costs, in order to keep her supplied with war materials, food on which she depended, and to service the protection of the gateway’s to the Atlantic.

In quieter times, Germany had sailed their navy on courtesy visits to many countries, and had become extraordinarily familiar with Europe’s maritime geography. Among her main interests, was the importance of the Atlantic Approaches – those to the north and South of Ireland. Of course they were not only ‘approaches’, but ‘exits’ also.

WW1 in the Irish Channel.

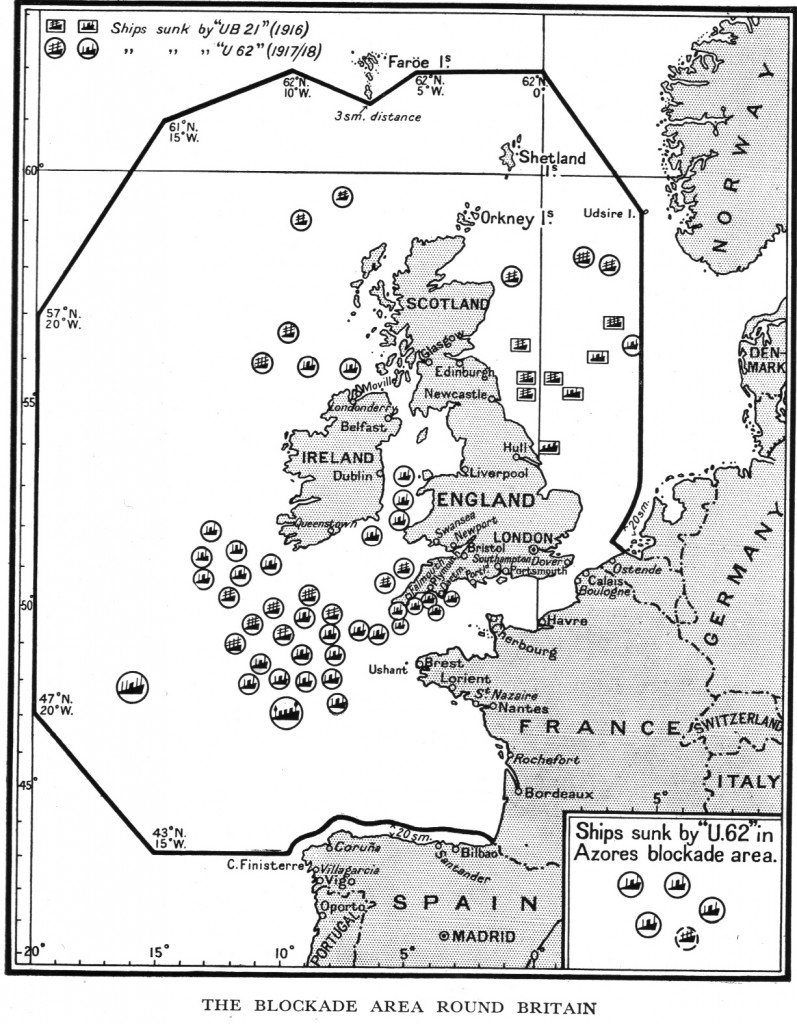

In 1917, Germany piled her U boats into these areas in order to choke off Britain’s supply corridors. And not only there, but they pushed on into the North Channel, the Irish Sea and the George’s Channel, all which we might call the Irish Channel. Here in the ‘quiet lake’, they attacked fishermen, merchant and naval ships, and the mail boats – the fastest ships in the channel.

Attacks in the Approaches were devastating and rattled the nerves of the British Admiralty. There was a terrible loss of ships, men and material. The U-boat men perfected their methods and even began early attempts at ‘pack attacks’. Fishing boats to large liners, and even battleships, fell victim to their onslaught, but the actions were largely unknown about. Power over the press amounted to the same thing as it does today – power over people. Censorship was total, and the general public in Britain and Ireland were unaware of the scale of the German submarine campaign being fought on their shores.

Things were slightly different in the Irish Channel. Both sides of the channel were lined with ports, where a huge number of ordinary citizens lived. A return trip across the channel might only last 24 hours, and any news, such as being attacked by a submarine, quickly spread among the close knit port communities.

During the four years preceding the commencement of hostilities, there were at least 694 incidents of shipwreck around the coast of Ireland. During the four years of the war, there were at least 1763 incidents*.

The threefold increase needs no explanation but the figures are what they always are – just figures. The statistics do nothing to help us understand the terror that was brought to sailors and their families in these waters, because no one knew about them. The port towns were alive with whispers, and worry for men-folk spread from one narrow street to the next, men who had to sail come what may. Whispers and here-say is one thing, but when the facts escape official record, that’s what they remain.

The slow vessels, such as fishing vessels and old steamers, were sitting ducks, and were often sunk by the deck-gun on a submarine, after it surfaced. In just a few cases, reports of sinkings became acrimonious, when it was said that the submarine commander failed to give sufficient notice to abandon their vessel or attacked the lifeboats. Researches show that there were few, if any, such incidents and that, sailors on both sides, by enlarge, stuck to honourable conduct.

There are so many incidents that one can choose to exemplify the conduct of the U-boat campaign in the Irish Channel or what it otherwise might be called, ‘U-boat Alley’**. The ones that stand out for me are the sinking of the pilot boat Alfred H Read in Liverpool Bay, the Guinness ship W M Barkley, the Wexford steamers Formby and Conningbeg and of course, the ship whose loss touched hundreds, if not thousands of families throughout Ireland and the UK, and others much further away – the mail boat Leinster.

The reasons, these and many others are of particular interest, was the terrible suddenness of the catastrophes, and an almost complete loss of all who were in the ships. Some incidences display an almost cavalier attitude by the authorities to a sophisticated enemy. One could not have provided escort protection for all the ships crossing the channel at the time, but some incidences demonstrate a misunderstanding and disregard for the competence of U-boats and their commanders at the time. The Guinness sailor, McGlue, and his account of his escape from a U-boat attack, is fascinating, and shows just how ignorant the general public and sailors were, of the enemy that patrolled on and beneath their seas.

*These include sinkings, attacks and encounters with enemy submarines. It does not include a comprehensive account of ships lost or attacked off the west coast of England and Wales.( irishwrecks.com )

**The author has adopted the term that was sometimes used to describe the North Channel, the Irish Sea and the George’s Channel as one – the Irish Channel. Given that there was so much German submarine activity in these areas, he has also adopted his own – ‘U-Boat Alley’.

Alfred H Read

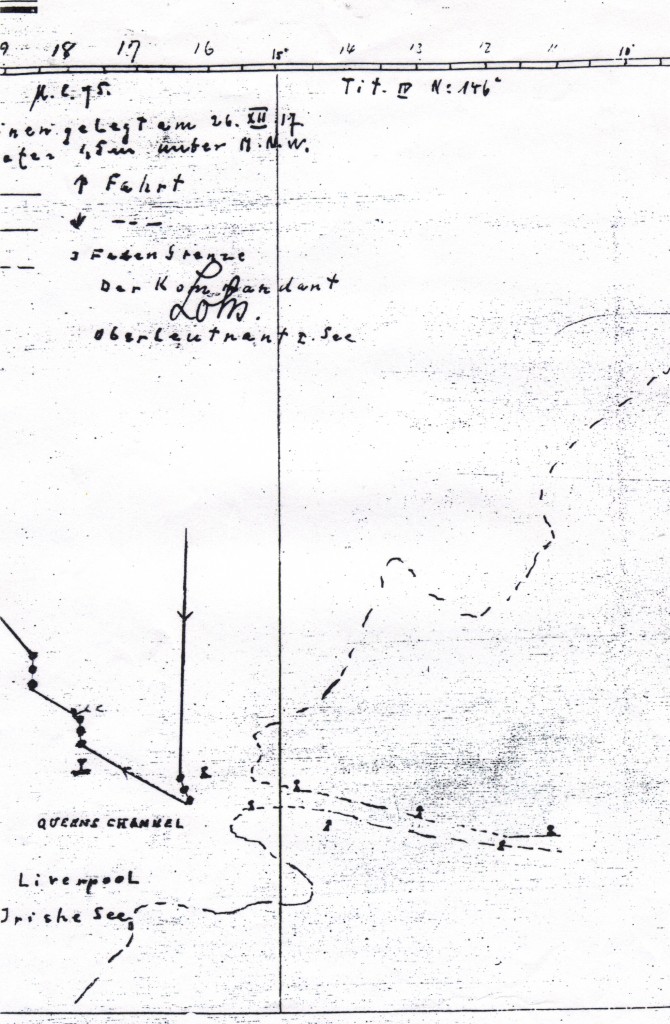

Liverpool was bustling with troop carriers, warships and merchant ships. No one suspected that a German submarine might get into the Bay and attack Britain’s industrial and maritime heartland. The steam cutter, the Alfred H. Read. (probably named after the manager-owner of the British & Irish Steam Packet Co., A. H. Read), also known as Pilot Boat No.1, was lost at the mouth of the Mersey on 28 December, 1917. She struck a mine, after commander Lohs in UC-75 dropped their deadly ‘eggs’ across the entrance to the Mersey, in anticipation of the arrival of the huge troop-carrying Leviathan.(ex. Vaterland).

Servicing waiting and approaching ships, the pilot cutter was packed with forty-one personnel, only two of whom survived. Nineteen pilots were lost; the remaining twenty who died were mixed service personnel and radio operators.

Extract from log of UC75 showing how mines were laid across the Liverpool Bar and sank the Alfred H Read

This was another of those vessels who didn’t have a choice. The ship was commanded to sail into the Bay daily, delivering personnel and boarding ships for inspection, and guiding others up the channel. It was not a large ship and the effect of the exploding mine was catastrophic.

W M Barkley

Because of the world renown Guinness brewery connection, and an excellent first-hand account by one of the ship’s crew, this next tragedy has has attracted some attention. Thomas McGlue’s, Barkley story, was published many years after, and although in ways sad and regrettable, it is also enlightening and even entertaining.

The Barkley was carrying stout on the Dublin-to-Liverpool route when the war broke out. Mr McGlue joined the ship at the age of thirty-two in 1914, and remained with the Barkley as steward until the end of the war.

Nervousness at Dublin Port had been increasing well before the Barkley’s final journey. A growing number of rumours of U-boat attacks just outside the harbour, had the port in a heightened state of tension. Along with a small number of other vessels, the little steamer sailed from Dublin, on a day when some of the bigger ships remained in port, in fear of the whispered ‘invasion by submarines’.

It had been a week of gloomy anticipation around Dublin port. Arklow-born, captain Gregory, in command of the W M Barkley, had traveled to the Guinness shipping office at North Wall quay on several occasions, to see if the suspension of sailings had been lifted. The port had been closed earlier, due to the escalating number of fatalities from submarine attacks in the Alley. Captain Gregory was informed on Thursday evening that, the port might reopen the following day. The crew was also notified, and the next morning, Friday 12 October, Captain Gregory returned to the Guinness office.

Restrictions on sailings had indeed been lifted, and the captain collected the Barkley’s papers and her crew, and made ready to sail with a cargo of stout for Liverpool. Whether or not captain Gregory, or anyone else for that matter, were aware, the port would close again, almost immediately after the Guinness ship had left, for exactly the same reasons as earlier.

The W M Barkley shoved off at 5.00 pm, and steamed down the River Liffey, flanked by Dublin’s fading lights – yes, the lights were not doused. Little did the crew of the Barkley know, that as soon as they would lose sight of Dublin’s lights, her run of earlier good luck in the channel would come to an unexpected end. Given the particular U-boat commander that had patiently lain in wait for a target, her fate had almost certainly become inevitable.

Known to be one of the most determined in the Fleet, Lohs had taken command of the Flanders minelayer, UC-75, from Captain Paech, on 4 April 1917, and displayed an experienced familiarity with the waters between Ireland and England.

The evening of the 12th arrived, and Commander Lohs lay in wait off the Kish light vessel, seven miles from Dublin. The little steamer was belching out its black smoke, as it struggled along at about seven knots, on a course which would bring it fatally close to the lurking U-boat.

The attack commenced at about 07.45 pm, when Commander Lohs surfaced about 300 metres from the Barkley, and let loose with one of his forward torpedoes. Launched by a burst of compressed air, the deadly tube of high explosives sped towards the Guinness steamer, containing the helpless sailors and all those barrels of stout.

Thomas McGlue wrote a very fine account, which appeared many years later in the Guinness in-house Harp magazine, under the title, ‘Recollections of the W. M. Barkley’.

“I was in the galley, aft of the bridge. I was just reaching out to take a kettle off the fire to make a cup of tea for the officers. When we got the poke, the kettle capsized and shot the boiling water up my arm to the elbow. The galley was filled with steam and I said a few hard words, but apart from that there wasn’t much noise – not a murmur, in fact.

The port side of the ship was locked to keep it dark, so I went through the engine room and out on the starboard deck. There was a lifeboat hanging there, hanging by one end to the forward fall. The Barkley was doing her best to go down, but the barrels were fighting their way up through the hatches and that kept us afloat a bit longer – in fact, it’s the reason any of us got out of her.

The master gave three blasts on the siren and then I didn’t see him anymore. I climbed into the boat and a mate gave me a knife to cut the fall and the painter. The boat dropped clear and dipped under a bit and we had to do some fast bailing. The other fellow was all for us getting away while we could, but I said No there’s more than two of us here and they’ll want to come along. Then the gunner came up – we had one gun on the after deck but he wasn’t at it when we got the poke; as a matter of fact, he was in the galley with me, waiting for some hot water to do his washing with. I don’t know where he’d got in between.

The gunwale of the lifeboat had been ripped when we were hit and the gunner gashed his leg on it, getting in. Then another A.B. [Able-bodied seaman] jumped in and that was four of us. We rowed away from the Barkley so as not to get dragged under, and we saw the U-boat lying astern. I thought she was a collier, she was so big. There were seven Germans in the conning tower, all looking down at us through binoculars.

We hailed the captain and asked him to pick us up. He called us alongside and then asked us the name of our boat, the cargo she was carrying, who the owners were, where she was registered, and where she was bound to. He spoke better English than we did. We answered his questions and then asked if we could go. He told us to wait a minute while he went below and checked the name on the register. Then he came up again and said: “I can’t find her.” He went back three times altogether. Then he came back and said: “All right we’ve found her and ticked her off.” We said can we go, but there were two colliers going into Dublin and he told us to wait until they were to windward and couldn’t hear our shouts. Then he pointed out the shore lights and told us to steer for them.

The submarine slipped away and we were left alone, with hogsheads of stout bobbing all around us. The Barkley had broken and gone down very quietly. We tried to row for the Kish light vessel but it might have been America for all the way we made. We got tired and my scalded hand was hurting. We put out the sea anchor and sat there shouting all night.

At last, we saw a black shape coming up. She was the Donnet Head, a collier bound for Dublin. We got into Dublin about 5 AM and an official put us in the Custom House at the point of the Wall, where there was a big fire. That was welcome because we were wet through and through and I’d spent the night in my shirtsleeves. But we weren’t very pleased to be kept there three hours. Then a man came in and asked “Are you aliens?” Yes, we’re aliens from Dublin. He seemed to lose interest then, so we walked out and got back into the lifeboat and rowed it up to Custom House quay. The Guinness superintendent produced a bottle of brandy and some dry clothes and sent the gunner off to hospital to have his leg seen to. The rest of us went over to the North Star for breakfast. And later, after I’d had my arm dressed – the doctor said the salt water had done it good – the superintendent gave me a drayman’s coat to wear and put me in a cab.

I was glad to get back to Baldoyle, because I’d left my wife sick and was afraid she’d hear about the torpedoing before I could get home.”

Thomas McGlue retired from Guinness in 1947 at the age of 65, but even then, he could not contain his love for the sea. He attempted to re-enlist at a Dublin shipping office, where he was kindly advised that enough was enough, and unlike many of his earlier shipmates, Thomas lived a ‘gentleman’s life’ for many years.

Four Dublin men and Captain Gregory from Arklow, were killed when the W M Barkley was torpedoed.

The Formby and Coningbeg

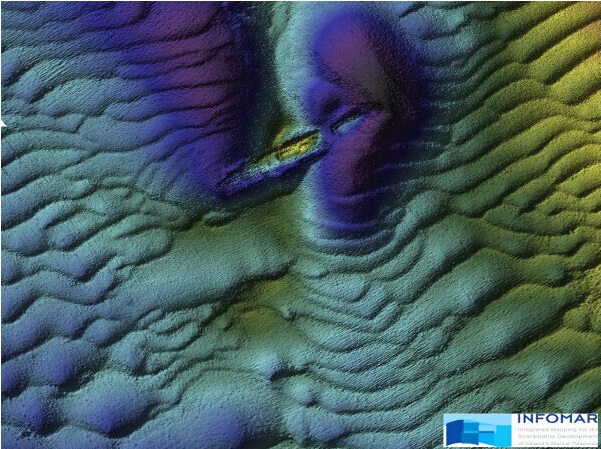

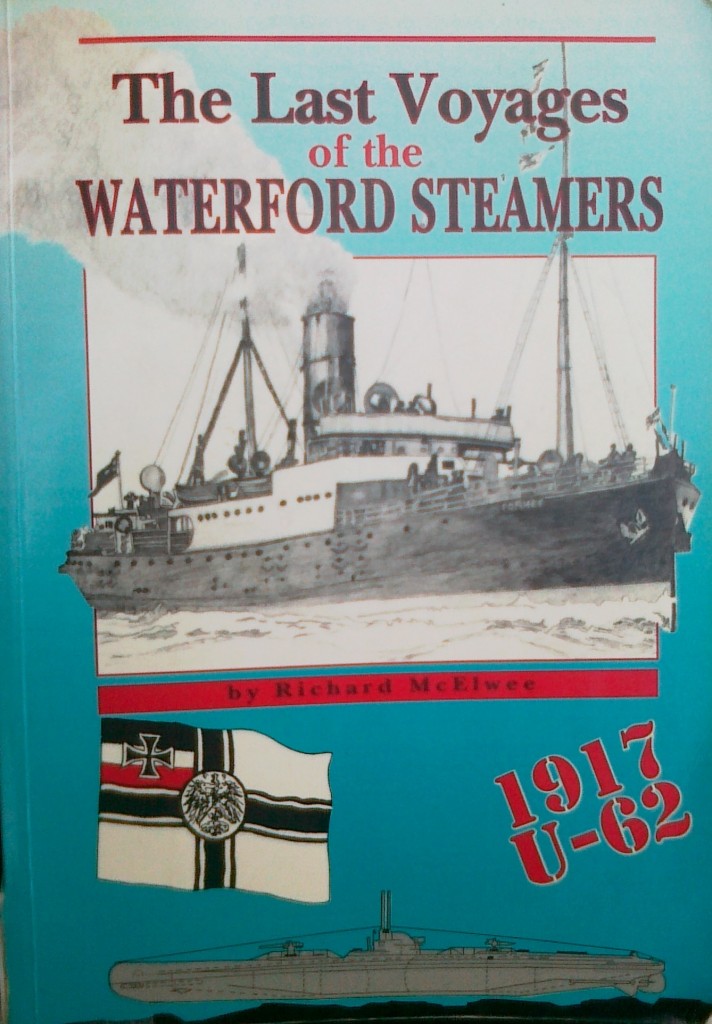

These two Waterford steamers were considered modern and were fairly typical of their day. The twin sinkings occurred within a couple of days of each other, 15th and 17th of December 1917, while sailing from Liverpool to Waterford. The attacks were carried out by commander Ernst Hashagen in U-62, and the result was a total loss of both steamers, and all aboard them. 77 crew and 6 passengers.

Although the ships were built for cargo, with generous accommodation for passengers, there were few on board while they carried a ‘general cargo’. The majority of the crew were from Waterford city. The long list also included gunners who manned the defensively armed steamers.

The most impressive research of these losses was by Richard McElwee, in ‘The Last of the Waterford Steamers’, which includes one of the most remarkable aspects of the attack. It’s recollection in 1938, by the attacker, Ernst Hashagen, published in his war memoirs, ‘The Log of a U-boat Commander’ or ‘U-Boats Westward’.

U-62’s log records the sinking of the Formby on the 15th. quite starkly, and without any emotion.

7.58 PM. Night dark W3-4. – Bow shot No.1 tube1, C/O6D torpedo, 2.5 depth. Opponents speed 11 kn. Interception angle 80 degrees. Distance 500m. Hit in engine room. Vessel unknown nationality. After clearance of the smoke of the explosion (3-4) minutes after the strike, the ship sinks with all hands. Position of sinking Quadrant 081-D4 west.

Differing, the attack on the Conningbeg is covered in some detail in his memoirs, and is quite moving. Hashagen had spotted the steamer coming down the channel and began to shadow his unsuspecting quarry, at times, putting on all speed in order to put the submarine in a position for an attack. Writing one year before going to war once more, he wrote.

….“It is rather dreadful to be steaming thus alongside one’s victim knowing that she has only ten or maybe twenty minutes to live, till fiery death leaps from the sea and blows her to pieces. A solemn mood possesses the few upon the bridge. The horror of war silences us. Every one of our orders, every movement, every turn of a wheel is bringing death nearer our opponent. All is exactly settled in advance. We too, have become a part of fate….Attack commencing…Full speed… Attack! Both tubes ready…First tube standby…First tube fire!!!…

On the tower we all stare at the dark ship. Suddenly, a gigantic tongue of fire in the night! A powerful explosion follows. Our ear-drums tremble…We see the ship break in two pieces, with flames and smoke. The forepart goes down like a stone. The after part heaves up, glowing and hissing…once more the flames blaze up, then everything fades into darkness. A single light is seen upon the sea, flickering miserably. It is the vessels night life buoy, which has released itself and burns now for a gravestone above the unfortunate ship…”

Even considerably abbreviated, the account is moving stuff. The two Waterford steamers were attacked in the night, no one was saved and no one heard their screams. Worse, for a long time they were reported – ‘missing, presumed drowned’. Not even Hashagen’s conscience escaped.

The Royal Mail Steamer Leinster – The Mail-Boat

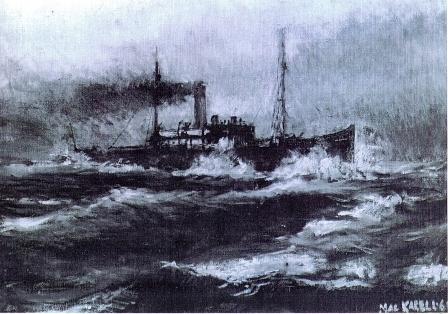

It might seem fanciful to describe a ship as more than what it is; a fabrication of metal and timber, capable of travelling across the water. However, in this case the ‘mail-boat’ was different. There were not one, but four of these fine and identical ships, travelling to and from England, and due to their exceptional speed, were called ‘greyhounds’.

The company was also exceptional, and seen as so, almost representing Irish interests in commercial competition with British ones. The valuable passenger and postal trade, the company had long dominated, was constantly under threat from its competitors. Constantly sniping at its performance, and lobbying Whitehall for changes to be made to its contract.

On a different level, the ships were probably comparable to a modern 21st. century city-transport system – the steamers, representing the Four Provinces of Ireland, Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connaught, travelled around the clock all year long. They were seen as the principal and fastest mode of reaching Britain or Ireland, and in some style. They also represented emigration, bustling mothers, wives, and loved ones amid bundles of luggage, trundling along the windy piers, travelling for work in British industry.

During the war they also represented, not exclusively, a valuable asset to the war. Connected directly to railheads, they represented an important link in a veritable highway across Britain and Ireland, by which all manner of war material and personnel could be speedily transported. By the time the Leinster was torpedoed and sunk – the Provinces had carried thousands of service of various natinalities, and tons of military stores. One of the quartet, the RMS Connaught, was commandeered and lost in the English Channell doing just that, in 1917.

During the war years, the mail boats were often packed to capacity with troops and civilians. Warnings of submarines in the channel reverberated throughout the east coast ports, but the mail boats always put to sea. Under the time-critical terms of their mail contact, they were compelled to. Anti-submarine patrols were in operation, but often ineffective. Escorting the mail boats or any similar individual steamer, was operationally out of the question. In the case of the mail boats, it was also considered unnecessary, as the twin-screw steamers could travel faster than most of the naval patrol boats, and were defensively armed with trained gunners. (Most of the depictions of the mail-boats did not show the large gun mounted on the stern.)

Despite the fact that the mail boats were a specific target for U-boats – they were on their own.

It is a question that keeps coming up. If the war hadn’t ended so soon after the dramatic loss of the mail-boat, would Germany’s propaganda coup have made any difference? The answer, quite simply, is no. It was late in 1918, Germany had not developed sufficient weapons and trained enough men to make the difference and America had. Good submarine commanders died, and were not replaced by enough well trained and experienced ones.

Commander Ramm was one of these. Well trained – on paper, but with little ‘up against the enemy’ experience. His third outing in command of a submarine, the young officer took his boat and crew out of Heligoland on September 26th 1918. One of the later more advanced UB class of submarine, he proudly proceeded in UB-123 on his patrol to the North Sea and his ultimate destination – ‘U-Boat Alley’.

After little success in British waters, Ramm continued ‘North About’ the Orkneys, and sank the steamer Arca on October 2nd. This was followed by a disputed sinking of the SS Eupion of the Shannon Estuary on Oct 3rd. In their 180ft. iron tube, Ramm and his 35 comrades arrived in the Irish Sea on the night of the 9th, and remained off the Kish, in wait for the scheduled arrival of the mail-boat.

Despite warnings of submarine activity in the Channel, the Leinster raised the gangplank and left the quayside in Dun Laoghaire at 08.53 AM. She was carrying mails, baggage, stores, military personnel, British, Canadian and American. She also carried a full complement of crew, postal workers and civilian passengers.

Ramm navigated to position himself at right angles to the port side of the approaching steamer. At 09.45, when the mail-boat was in range, he fired and missed. The first torpedo being premature and crossing the ship’s bows. The second didn’t, and struck the ship on the same side in the postal sorting compartment situated forward. The damage and loss of life was catastrophic, instantaneous for almost all of the postal workers, and probably would have sunk the ship.

Commander Birch gave the order to bring his ship round, in the hope that he might make the shore or at least get nearer to it. The ship still had way on, and was able to perform the maneouvre just before she began to settle. Ramm did not move, and within minutes, as the life boats were being lowered from the sinking ship, he fired a third and fatal torpedo into her.

The ship was already in a confused scramble of screaming passengers, and those already dead. Some boats were got out before the ship sunk, and as with many shipwrecks and sinkings, the behaviour of some was cowardly and regrettable. The second explosion ripped the ship open and tossed metal and bodies all over the place. Commander Ramm did not surface and just disappeared, but never made it back to Germany. It is believed he got snared in the unprecedented web of mines being constructed by the Americans across the full width of the North Sea.

As with most German successes, the British censoring machine went into overdrive and attempted to stifle news of the attack on the prestigious mail boat. It proved impossible. The effects of the sinking, seen by passing vessels, explosions, the bodies washing up and being recovered all along the coastline – so many stories everywhere.

Despite initial attempts to prevent publication, this was quickly reversed and publication of the sinking and the terrible aftermath was encouraged. The reverse spin proved a valuable propaganda coup – the ‘Murdering Hun’ and so on.

It was reported that there were 771 people on board the Leinster when she was sunk and that 501 were killed. These figures have increased since and may continue to do so. Not an ‘Irish’ sinking, the Lusitania, I consider the sinking of the mail-boat Leinster to be the greatest catastrophe in the history of Irish sea tragedies.

Far from marking a new era of success for the U-boats, the end was already being prepared for by both sides, and the war ended a month later.

How can the perennial occupation, that is war, be commented on with any hope or rationale, when it remains in so many places, an only or preferred means of settling one’s differences. The ‘rules of war’, such a pointless and stupid phrase, evidently now being, a truly redundant and hopeless aspiration.

Not only in trenches on foreign soil, did Ireland play her part, but so too in her own waters by those who never even knew.

Bent down is the owner of the wreck of the Leinster, Desmond Brannigan, surrounded by the divers who recovered the Leinster’s anchor. It now forms part of a fitting monument situated in Dun Laoghaire harbour.

Utube video ‘Story of the Sinking of the RMS Leinster’

Roy Stokes, October 2013.

PLEASE NOTE:- All images, text and video contained in this post, can not be reproduced without permission of the authors or accredited artists.