‘West Britain’

It was Tuesday, the 31 day of August, 1785, and just a few miles south of Dublin city, the inhabitants of the grand harbor town of Kingston were sleeping soundly in their beds. A number HM ships of the line had arrived earlier in the week for naval exercises and shore leave had been liberal. Buntings and flags flew from buildings up the hilly streets, and a mood of holiday and some celebration had settled over the town.

Kingstown, Dunleary as it was, and Dun Laoghaire as it is now, is not known as a ‘port’. Unlike ports, it is not naturally situated on an estuary or a river mouth but was created as a result of lobbying for a safe havonage, and an alternative to the Port of Dublin. A magnificent harbor, it was built to replace a tiny harbour that served a few fishermen, and then some modest brigs, opposite the Coffee House at Salthill. The harbour was situated under some cliffs at the northern end of Kingstown, where the Purty Kitchen pub is now. Why it was named Kingstown is obvious, and was a very popular choice at the time.

For months earlier, the honorable gentlemen in the House of Commons, including Irish MPs, demanded that the might of the British Empire, in the form of its great navy, should be more visible around the coast of Ireland. The lobbying had its effect, and some of the great ships were assembled to do an imperial-type cruise around Ireland.

Naturally the ships should stop at the principal cities so that everyone could see just how powerful the navy was. This meant visiting the likes of Belfast, Dublin and Cork. In ports and harbours like these, the Royal Navy already had ‘guard ships’ permanently based, in order to maintain the imperial presence. However, by that time it was less to fight smugglers and invaders and more symbolic.

Captain Richard Dawkins, in command of the guard ship HMS Vanguard at Kingstown had been expecting the Royal squadron of ships, after he received word of their departure from Belfast. The big ships would not cross over the shallow bar of Dublin, but would berth in the harbour and roads of Kingstown.

As one might expect, Dawkins had given instructions that his battleship should be made ready for the anticipated cruise, and that all aspects of vessel should made ready for inspection.

The visit of her HM ships to Kingston had gone well by most accounts. Captain Dawkins dined with vice-Admial Sir W. Tarleton aboard the battleship Warrior and many of the sailors were released on the town by way of shore-leave which ended on Monday the 30th. The next day would be given over to double checking all of the ship’s riggings and fittings, and familiarising officers with the route and procedures of the cruise which would commence the following day, 1st of September.

The inhabitants of Kingston could often hear Vanguard’s large bell ring out it’s watches, but not on that morning. Moored at the ‘guard-ship moorings’ in the bight of Kingston’s east pier, the log of Vanguard, recorded that her large bell rang at 4 o’clock. The officer of the watch entered the wind being from NNW,force 3, followed by barometric and temperature readings.

When the bell rang again at 8 oclock, the crew were mustered, with the exception of; ‘Ordinary seamen and boys at seamanship instruction.’

What occurred next was never reported.

Following prayers on deck, a warrant was read out. Celebrations in the town a night or two earlier had reached an unacceptable level, and marines from the Vanguard were summoned. Scuffles followed, sailors were arrested, and their offences were later adjudicated aboard the Vanguard.

Captain Dawkins considered the matter serious enough to issue the following punishment, which was entered into the log as follows.

‘Read warrants – sentencing George Langler ABS., John Leaman ABS., Charles Royce Pte., James Hayden, Drummer to 42 days imprisonment in Richmond Bridewell Gaol.’

The men were transported to the Bridewell and processed for confinement. As inmates were not photographed at the time, but record of their admission makes interesting reading.

J. Hayden, drummer, 27 years, guilty of ‘absent without leave’. Distinguishing mark; Shot wound, left thigh.

C. Royce, marine, guilty of disobeying an order. Distinguishing mark; one tooth out of upper jaw.

G. Langler, ABS, guilty of AWL. Distinguishing mark; none.

J. Leaman, ABS, guilty of assault. Distinguishing mark; Shape of heart tattooed left arm. Cut mark over right eye.

Two of the men could read and the other two could read and write. All were sentenced a similar period of detention – 42 days hard labour. Seeming the same, Leaman was confined for 6 weeks?

By midnight on Tuesday, Vanguard had let go her moorings in Kingston and proceeded into Dublin Bay to form up with the other ships. While at ‘single anchor in Dublin Bay’, she had taken on a consignment of ‘fresh beef and vegetables’ for the anticipated cruise which would commence on the following day.

The wind had remained light form the ‘NW’ throughout the night and became ‘calm’ with morning.

At 8 o’c Wednesday, 1st September, the order was given on the Vanguard to ‘muster by division and to cross the Royal Yards’

Her single anchor was weighed at 10.30 and ‘she proceeded under steam out of Dublin Bay with the squadron in single column line ahead. At 11.40 the squadron rounded the Kish light vessel which is where Achilles parted company for Liverpool.

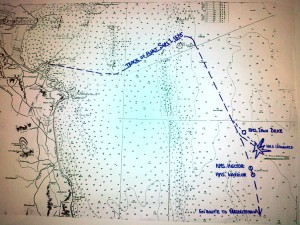

Steaming south now at a leisurely 6 knots were the pride of HM navy, Warrior, Hawk, Hector, Vanguard, Iron Duke and Penelope.

Housed in pride of place aboard the Vanguard, was the beautifully ornate ‘officer’s silver’ valued at £260. Complimenting the fine silver, the ship’s wine cellar was valued at £300, an amount equivalent to twenty years wages for one of her able-bodied seamen. Such were the contrasts between officers and crew aboard the HMS Vanguard and six other accompanying ‘ships of the line’ as they left Kingstown behind that faithful morning.

Having maneuvered around the north end of the notorious shallows of the Kish Bank, their new course took them down the outside of the Kish Bank, with HMS Warrior and HMS Hector ahead of HMS Vanguard and HMS Iron Duke. Their speed had increased a tad to 7-8 knots.

Having just passed the east Kish buoy, Admiral Tarleton in the Warrior gave the signal ordering the Vanguard and the Iron Duke to take up a new position abreast and to seaward of his own. In attempting to follow this order, the careers of several fine officers aboard these two vessels would end in ruins and ignominious notoriety.

The Collision

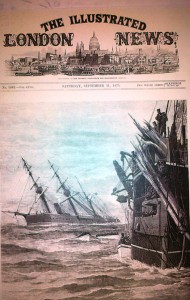

It was about midday, hazy conditions gave way to a captain’s nightmare, in the form of a sudden thick fog. It enveloped the formation, making the two pairs of battleships invisible to each another. Not only could the ships not see each other, but sailors later reported that they could hardly see the yards.

Having lost sight of the other ships, and with no other means of communication, the Warrior and Hector remained together and continued to Queenstown, completely unsuspecting of the calamity about to befall the IronDuke and Vanguard, or of the undesirable place it would insure them in the history books.

Like many accidents, there were several separate circumstances, which alone, might later have been considered only minor infractions, but when they converged, spelt disaster. During the ‘coming up’ manoeuvre, Richard Dawkins captain of the Vanguard, handed over the bridge to his officers and went below to lessen the ship’s burden of carrying so much fine food and wine. Unbeknownst to him, his close friend captain Hickley in the IronDuke had been overcome with a similar desire.

After the fog had first thickened, the officer on the deck of the IronDuke became a little concerned about loosing the Vanguard and made the fatal error of veering slightly to port, which he compounded, by slightly increasing the ship’s speed. By itself, the manoeuvre might have had no lasting consequences but at the same time, and from suddenly out of nowhere, the officer on deck of the Vanguard caught site of a converging sailing ship emerging from the fog.

Both captains had by now returned to their bridges and unaware of the new position of the Duke, Captain Dawkins made a quick signal before drastically reducing speed and turning the ship to port in order to avoid ramming the sailing vessel.

Unfortunately, by then the IronDuke had caught up on the Vanguard, and could just make out her sister ship looming out of the fog, but alas it was too late. The IronDuke ploughed into the Vanguard at amidships on the port side. Those aboard the Duke could only assist the doomed vessel by helping to rescue her crew before she gave a final lurch and plunged 17 fathoms beneath the waves.

Such incidents are nearly always best described by those who had first-hand experience in the affair. Captain Dawkins recorded the following in his log, which was probably, post event, but soon after.

0.10 PM. Formed 2 columns as per signal. Whilst in process of formation. Steamed into a thick fog. Ships reported right ahead.

12.50. HMS Iron Duke close to on port beam – ram into the ship striking her with her stern abreast the engine room which filled the engine room in about 5 minutes. Closed all water tight doors. One watch manned the pumps, the other watch proceeded to get the boats out. Iron Duke closed and sent boats to assist.

1.30. Finding pumping useless, and being of opinion that there was no chance of saving the ship, it being also the opinion of the principal officers on board, as she was setting down very rapidly. Ship’s company were ordered to leave.

1.45. All hands clear of ship.

2.00 HMS Vanguard sank stern first heeling over to starboard in 16 fathoms of water. Kish Lt Vessel NNW 8 ¾ miles, Bray Head W by N 11 miles.

All hands saved.

Captain Dawkins last entry was signed by R.Dawkins and witnessed by Lt W.W. Hathorne, officer of the watch.

When word reached the Bridewell in Dublin, what thoughts went through the minds of the Vanguard’s four shipmates banged up 42 days.

Pound of Flesh

The Royal Navy will not suffer an embarrassing loss of a fine battleship without some piper being paid. The ensuing court-martial was swift, and the Admiralty, who was said to have belonged to a bygone age of ‘wooden walls’, handed down stiff justice.

The engineer and carpenter Tiddy, poor fellows that they were, got it for not plugging the 9’x3’ hole with canvas. Despite the proximity of the lucky sailing ship, the officers on deck of the Vanguard got it for slowing down. And even though there was no court martial in respect of the Duke, her officer on watch, Lt. Evans, was arbitrarily and severely reprimanded for speeding up. It was later said, that the young officer went to the grave with repeated nightmares of the fatal collision.

Both captains had thirty-five years experience afloat with the RN but neither service, nor the fact that his judgement had saved 360 RN seamen from drowning, spared her captain from disgrace. His ‘ship was dismissed’ and Dawkins was never employed again. Amongst the accusations levelled at him was, that he did not do all in his power ‘to get all available pumps worked’. His explanation, that as there had been a loss of steam, leaving the pumps operational by hand only, and being totally inadequate in preventing the ingress of an estimated 50-600 tons of water per. min., was dismissed. The decision was very unpopular and the mood of the day was reflected in the following extract from a ditty heard in music halls.

‘In steering’ says he, ‘to avoid a big smash

I used common sense d’ye see.’

‘We know nothing at all about that at Whitehall’

Said the Lords of the Admiraltee.

–

For the Adm’rals all who just sit at Whitehall

Should know about ships d’ye see.

We must clear out those frauds who proclaim themselves Lords

From out of the Adm’raltee.

Captain Dawkins lost his rank and esteem at the hands of those who he had served faithfully since he was a very young man. And although another loss is commonly only jokingly referred to, captain Dawkins also lost his dog on that ill-fated day. Not just another animal, but one he considered to be his ‘friend’.

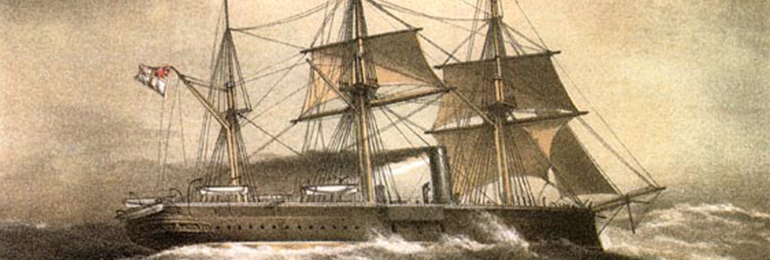

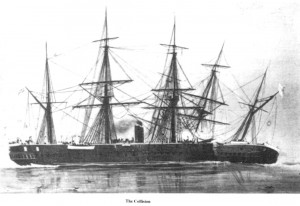

A Ship Best Forgotten

The Vanguard was rated as a medium ironclad battleship. That is, she was mainly built of iron and heavy timber, which in the central area of the 280ft. ship consisted of teak ‘backing’ ten inches thick behind 8 inches of iron armour. The principal armaments of ten twelve ton 9” MLR guns were housed in a central ‘battery box’ situated on the main and upper deck, which itself was constructed of iron 5 inches thick.

The 6034 ton ship belonged to a class known as ‘Audacious’ and was one of four almost identical ships built for the Royal Navy, Audacious, IronDuke, Vanguard and Invincible. The Vanguard was laid down at the well the known yard of Lairds Bros. at Birkenhead in 1867, and later finished by the RN in 1870, after which she was established as the First Reserve Guardship of the Eastern Irish district, and was based at Kingstown.

Some unusual features of these great ships was their huge sail area, a detachable funnel and twin screws. Replaced in the other three by a Griffith’s design, the Vanguard screws were the original Mangin design and present a magnificent site on the wreck today. Both shafts were driven by two separate pairs of engines, on which there were two sets of 16’ twin bladed propeller assemblies. This design is so unusual, that these are of considerable interest to naval architects today. Curiously, when completed in 1870 she was the fastest of all the RN ‘medium’ size battleships, accomplishing 14.6 knots over the ‘Plymouth mile.’

All of the foregoing design features represent a term applied to many ships of this era, i.e. being in transition. These progressions of sail to steam, wood to iron etc. were cautiously adopted in RN vessels, and in addition, these four, maintained another unusual feature dating from the very early days of warships, a ram. This eight-foot protrusion was situated on the stem below the waterline and the Duke’s proved to be most effective when it pierced a massive hole in the Vanguard. Thus establishing the embarrassing record; the first RN ship of the line to have been sunk by collision. The large bulbous extension at the waterline of large modern merchant ships appearing quite similar.

Royal naval divers mounted a salvage expedition to the wreck and worked it for many months, recovering all the valuable gear that they could. Experts began to hover with all kinds of schemes for raising the wreck and suggestions for the improvements to underwater apparatus used by divers. One ‘expert’ suggesting it could be ‘bumped into Kingstown’.

Notwithstanding their hard work the naval divers failed to raise the wreck or recover its valuable guns. They did manage to recover the ship’s silver.

Abandoned by the navy, the wreck however, began to attract opportunists. Advised by captain W. Coppin, a formation of the Vanguard Salvage Company Limited later privately invited punters to invest in the raising of HM Iron Clad Steamship Vanguard. They failed in all respects.

The Marlin Sub aqua club Examines a Dead Battleship.

Having dived on the wreck of HMS Vanguard a couple of times, the Marlin sub aqua club decided in 1999, that this was a wreck worthy of special attention, and should become the focus for a diving project in 2000. The principal reason for its selection was primarily due to the fact, that the diving community had a unique shipwreck on its doorstep, which was hardly dived at all, and about whose overall condition there was relatively little known.

As the original builder’s drawings of the ‘Audacious’ class were available in the Maritime Museum in Greenwich, and provide so many technical details of the vessel, painstaking measurements of her remains in difficult depths and conditions were deemed unnecessary and were kept to a minimum. The method chosen to be most economical with finance and time, when compared against the quality and presentation of the expected results, was a video record.

The problems were not insurmountable but required careful planning. Our project leader, Philip Oglesby (RIP) began with winter lectures on the visual aspects available on the ship, construction, armaments and the circumstances of her loss. As the depth range of 30-52 meters is most unusual for a shipwreck in the Irish Sea, a programme of training in the use of extended range techniques was initiated.

After the necessary permissions were obtained from Duchas and the wreck’s Irish owner, the team was joined by the amateur but enthusiastic cameraman, John Peare. It then only remained to choose the targets which would give the best picture of her present overall condition. These were selected in order of their possible uniqueness, bow, guns & battery box, capstans, ship’s wheel and stern section.

The survey began by connecting surface marker buoys to various positions on the wreck and interconnecting with guidelines below. Filming began at the end of June, and a total of 40 (At least two divers on each) decompression dives were completed over the following ten weeks.

Conditions prevailing in the Irish Sea are such, that it was never expected that all of the footage recorded might be of presentable quality, but we did film all of the designated targets and some excellent sequences were achieved in July. A detailed study of the ship’s main wheel assembly from the main deck was carried out, which was immediately followed by recommendations to lift and preserve it. The bosses of the Mangin propellers are at 46 metres and were visited three times in order to confirm the make-up of the assembly, which some sceptics had declared, was not possible.

It also quickly became the view of the Marlin dive team that captain Dawkins knew exactly what becomes of iron ships with big holes in their bottom, and made the correct decision when he abandoned his ship to save all of her crew. We can confirm from observations made of the collision damage to the ship, that the reports by the divers of the day, on the huge vertical gash behind the battery box on the port side, were indeed correct.

Receiving no mention in reports researched, and situated below an area of intact hull under the obvious collision area, there is another huge hole in the hull. Extending to the seabed, this is the damage that was quite likely caused by the ram, which was said not to have penetrated the inner hull but out of which we made an exit during a dive in the lower deck!

Our main enemies were poor light, depth and time, weather, bad water clarity and disappearing marker buoys. The project was a true adventure and the results were so pleasing, that they spurred the club to initiate the making of a full documentary film in 2001.

The Best Diving

Diving on the HMS Vanguard remains one of the most exciting in the British Isles. The results of our extensive diving on it show; that this shipwreck is unique, and apart from the collision damage and the results of early but minimal salvage, she remains intact from stem to stern. Healed over at about 30 degrees to starboard, she lies east-west, stern-stem and excluding her rigging and masts she contains all of her fittings, armament, winches, capstans and screws.

Once more, it is surprising to discover, how we in Ireland do not seem to comprehend the values that lie on our doorstep, a magnificent and unique shipwreck, unappreciated, and apart from noble but hollow sentiments in law, unprotected.

I have no doubt that given the continuous improvement in the water quality of Dublin Bay, this shipwreck will rightly become a burning curiosity for divers, when compared to the attentions received by the diminutive U260 and the historically barren Kowloon Bridge.

This wreck has received bad press in the past, for two reasons. Bad visibility and depth. However, there is no doubt that the visibility in the area of Dublin Bay has improved with each passing year, especially during July and August. The range of depth and the extent to which this shipwreck can be penetrated does gives cause for careful planning and leaves no room for a lack of discipline or messers. The GPS position of the wreck 14.2 miles SE of Dun Laoghaire harbour is Lat. 053.12.810, Lon. 05.46.000.

The best times to dive the wreck were; a half-hour before LW, and two hours before HW Dublin. (These times have been subject to variation.) The length of ‘slack water’ varied from 30-60 minutes.

Lastly, I wish to make the following plea to divers. It is important that we should recognise that this shipwreck is ‘different’. It is in fact unique, and that while visiting the wreck, you should temper your visit to recover souvenirs, with the view of leaving it for others as others have left it for you. Its future, which is by no means clear, is of course in the hands of the authorities.

2013. This wreck remains one of the most fascinating in northern Europe. Documentaries were made, as was a digital re enactment of events in 1875, which was produced by PLUTO.

To view clink on link

Death of a Battleship HMS Vanguard

or paste

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gXou8ireEgc

Thanks to;

- John Peare and his family for camera work and research material.

- Research & Photos from ‘The Black Battle Fleet’ by Admiral G. Ballard.

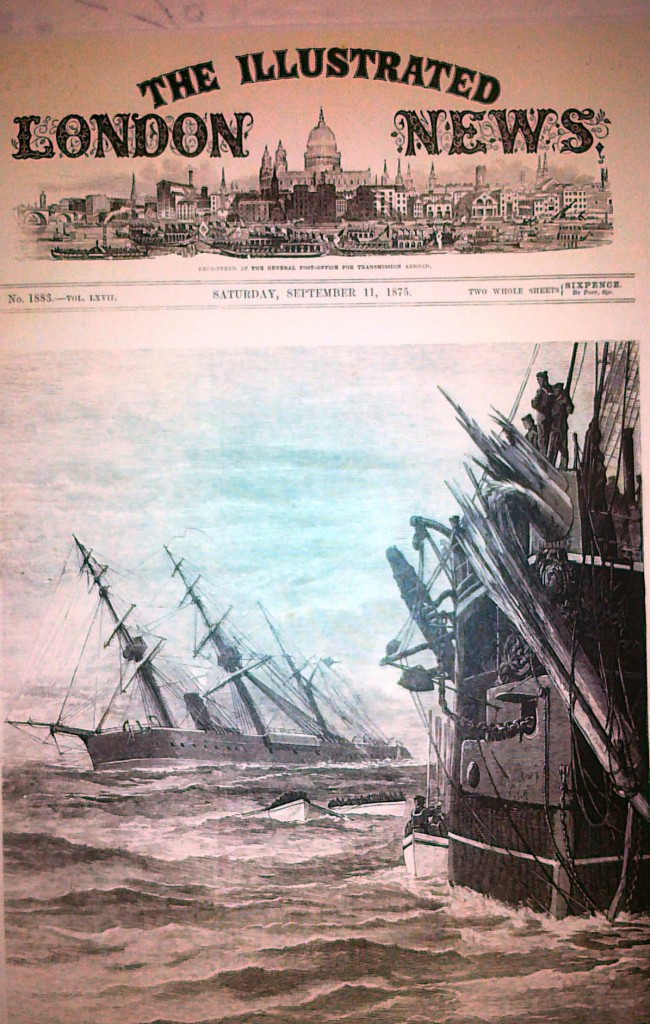

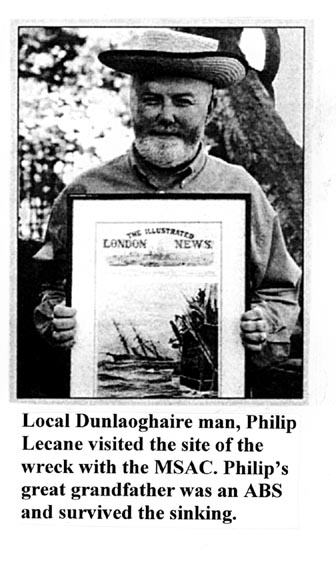

- Sketches in Illustrated London News by Captain S.P.Oliver R.A.

- ‘Great Outdoors’ & ‘Oceantec’ for generously sponsoring our air.

- And lastly, the ‘Marlin Team’.

Roy Stokes 1999/2013

PLEASE NOTE:- All images, text and video contained in this post, can not be reproduced without permission of the authors or accredited artists.