A Fresh Look at an Old Story

The story of the ‘Ouzel Galley’ is already out there – but is it one we can believe?

Our tale will be a collection of the facts. It won’t rely on any novels or on the ramblings of members of a secret society. It may disappoint the young at heart but it will be confined to facts, and will not claim to be the last word on the matter.

Our story will unfold in log entries as the facts emerge, over a yet undetermined period of time. So, add your twopence worth and let’s see where the wind takes us, me old shipmates.

First let me inform new and earlier readers that, additional updates and corrections will be an ongoing feature.

Last updated – 29/10/2023

___________________________

Log Entry, October, 2013.

The Ouzel Galley Society in the 20th century

Before we begin to look at a story that, although romantic and exciting, claiming to be historical, and been ‘out there’ for so many years, centuries in fact, and repeated ad nauseum, we must look in detail at the closely associated organisation, the Dublin Chamber of Commerce and its birth organisation, the Ouzel Galley Society – the heart of the story.

When Ireland’s charismatic Taoiseach, Bertie Aherne, addressed the Ouzel Galley Society’s members in 2005, on the occasion of its 300th anniversary, he congratulated them and spoke of the Society in following glowing terms.

“And nowhere is that better reflected, than in the Ouzel Galley Society, the society of which the largest Chamber in Ireland – the Dublin Chamber of Commerce, has grown.”.

The speech-writer clearly stating that, the Dublin Chamber of Commerce evolved from the Ouzel Galley Society.

And confirming the origins of that wondrous evolution once more;

“That was certainly fortunate for Dublin merchants embroiled in the Ouzel Galley debate! Those ambitions and ideas became the cornerstone of the Ouzel Galley Society, whose success as an arbitration forum later enabled the formation of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce.”

The address was brief, regarding the aspect of the Society’s history, but it did confirm the story still doing the rounds. Adding to the merriment of the gathering, the speech also alluded to that part of the lore that concerned the fickle position the unfortunate wives of the ‘sea-merchants’ from long ago had found themselves upon the return of the ‘missing ship’ – the heart of the matter.

“Standing here today, in Dublin Port, one can only begin to imagine the consternation surrounding the return of the Ouzel Galley to Dublin in 1700. Having long being considered lost at sea, the ship’s owners had received their insurance, not to mention the sea-merchant’s wives, who had turned elsewhere for comfort.”

When leaders of the Irish Government and presidents of large international corporations address annual bashes of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce and refer to its roots – ‘The Ouzel Galley Society’, who are they referring to?

When government leaders attend private meetings of the Ouzel Galley Society, who are they meeting? They are meeting other invitees, and past Presidents of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce – but why?

And is it not further puzzling that, if one types the word ‘Ouzel’ into the search box on the Dublin Chamber’s website, the only result is an article (not now visible) which appeared in the Irish Times, 2013, referring to Tall Ships visiting Dublin Port, and comparing the visit to the return of the Ouzel Galley, 300 years earlier.

The ‘story’ goes that a ship of this name departed from Ringsend for the Levant in 1695 with a cargo owned by Dublin merchants. After some years, the ship was considered missing and insurance claims with the underwriters were settled after lengthy arbitration. The ship made a surprising return, and again a difference between the underwriters and the original owners was settled by an agreed arbitration panel, which eventually named itself the Ouzel Galley Society’ in 1705, and continued with the good work.

The Ancient Society of the Ouzel Galley or the Ouzel Galley Club, as it was also referred to in some publications, did morph with the Committee of Merchants into the Dublin Chamber of Commerce in 1783, but the Society or Club continued separately until 1888, when it was dissolved. It was reconstituted in 1988, and has remained an appendage of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce to this day.

This Society has been almost exclusively populated with past Presidents of the Chamber, with exceptions been made for those ‘who have made a significant contribution to the economy of the capital’.

It is difficult to identify a similar relationship as that which exists between such a notable body as the Chamber, and a sister charitable organisation comprised of previous members, called the Ouzel Galley.

Fair enough, but why is this fact obscure? Why is the Dublin Chamber not proud of its roots and heritage and publicly proclaim it? Why does nothing about their origins appear in their literature or on their website – zilch? They own the domain name ‘ouzelgalley.ie’, but don’t use it – why?

After a number of pleasant meetings with a Enda McMahon, a biographer of the Chamber’s ex-presidents, I am informed that the Society meets for dinner and chat a couple of times each year, and agrees recipients for charitable donations – no more than that. One might think that this is more or less in line with what the Society always done – but from what I can gather, this is minus the arbitrations, for which it was established.

Not so.

(Enda McMahon enlightens us further in his new book, ‘A Most Respectable Meeting of Merchants’, a remarkable history of the Dublin Chamber of Commerce.)

Staying with the 20th century, the only evidence of this 309 year* old Society in public view, is a small stone plaque, over what was once (or thereabouts) a Coffee House and later the Commercial Buildings, and is one of the places where members of the Ouzel Galley Society met. Without any attribution, the plaque is purported to depict the Ouzel Galley ship, and was placed on this replica facade, which was erected to replace the old Commercial Buildings. These were demolished to make way for the structure there now – the Central Bank of Ireland.

The Society was supposedly designed along the lines of the Ouzel Galley’s crew of forty, titles and all, new entrants, ‘prayed to be admitted sailors on board’, and were led by their captain, who swore to; ‘Defend against all Pyrates both by Land and Sea’.

The Society’s records describe the unanimous election of John Macarrell in 1748 after the demise of its previous captain, Mr Porter.

One of the Society’s earliest stomping ground, the tavern, Rose & Bottle, was situated in the same area. The ambiance of this earlier tavern, might have influenced its later replacement meeting place, the ‘Ouzel Galley’. (Clubs being popular at the time, the Rose & Bottle was also a meeting place for members of other ancient societies.) My regret is that, I never got to a have a drink in the subterranean bar, ‘Ouzel Galley’, within the old Commercial Buildings – they certainly don’t make them like that anymore.

Inside the Ouzel Galley Lounge

A sign for the Ouzel Galley Lounge that hung on the Commrecial Buildings in Dame Street.

The publication, ‘Princes and Pirates’ by L.M. Cullen, published by the Dublin Chamber of Commerce in 1983, is an excellent read, and remains a most authoritative work on the subject of the Chamber and the Society.

Before Cullen, was the work of George Little, contained in a special edition of the Dublin Historical Record in 1953 and 1940, and before him in 1902, presented to the Royal Irish Academy by C.Litton Falkiner, a paper containing a short piece on the Society in the ‘Commercial History of Dublin in the 16th Century’. There have been numerous other specklings of comment and articles, but just like the one that has stuck, none differ, when it comes to the origins of the Society. As they all quite rightly point out – apart from Society lore, there are no contemporary records of the Ouzel or the Society until the middle of the 18th century.

Those seeking to discover the origins of the Ouzel Galley Society are often drawn to the publication, ‘The Missing Ship’ by W. Kingston, first published in 1877. This is a novel, and supposedly relies on the long-lost but found-again log of the ship Ouzel Galley. The ‘first’ publication date of this story and the period when the first notes for the novel might have been collected, is of particular interest, and will be addressed further on.

Despite the absence of any such log, there is little doubt that all accounts subsequent to the novel, ‘The Missing Ship’, used it to gather details and give credence to the supposed origins of a particular vessel by this name – and that of the Society. Unfortunately, this false premise remains firmly in place, as there are, or at least were, no other factual sources to draw from. Kingston’s book is a fanciful novel, set in the 19th century century and given its historical mismatches, it cannot be relied in any way, to represent a ship of that name from the 17th -18th century. It remains, as the author himself described, ‘an amusing sea tale’.

So it is now time to dig a little deeper, and to ask – when did the story, as it is known today, first appear?

* It is often claimed that, the Ouzel Galley Society has been in existence for more than 300 years. If we take it to have begun in the year claimed; 1705, then the period would amount to 309 years, at the time of writing, 2013. However, if we take commencement from the earliest evidence of the Society’s first ‘captain’ in 1748 (ref.Cullen), to its dissolution in 1888, together with its reconstitution in 1988, up to the year of writing, 2013, this would amount to 165 years. A long time no doubt, but nearly half the claimed.

End of log entry, October 2013.

_______________________________

Log Entry, November, 2013.

Don’t get me wrong, I want to believe this story, it’s a great yarn. However, as presented, it has problems. It’s strongest argument for authenticity is that, no one can think of a reason for concocting it.

Wikepedia – a terrific source of information, states:

‘No contemporary accounts of the Ouzel Galley’s adventures survive. The earliest reliable reference is found in Warburton, Whitelaw and Walsh’s History of Dublin (1818):

“Early in the year 1700, the case of a ship in the port of Dublin excited much controversy and legal perplexity, without being drawn to a satisfactory conclusion.”’

Why they used the phrase ‘case of a ship’ and didn’t mention the ship by name, is a little unusual – maybe.

The entry above is one the many statements regarding the origins of the Society which tends to mislead,

The earliest reference to the origins of the Ouzel Galley Society, might have been this book, but this was not published until more than 100 years later, in 1818, and it apparently relies totally on hearsay, or Society ‘lore’, as it was later put. Although published in 1818, the reference to the earlier year of 1707, is inescapable, but unsubstantiated and appears nowhere else, with the exception of Kingston’s later ‘story’.

There is little to guide us here, as the Society was well established by the time it went to print, and any concrete information regarding the Society’s origins does not seem to have ever appeared in print.

The reference does however, represent the first mention of such a ‘difficulty’ a ship in Dublin may have had. Published in 1818, it comes many years after the presentation of Maccarel’s painting of the ship to the Society, but before Kingston’s novel. Notwithstanding, it was surely not the only ship in Dublin at the time, with ‘difficulties’.

The ‘Story’

Let us look at the ‘story’ again, but in brief. The majority of it is down to the prolific novelist Kingston. A group, sometimes called a firm of merchants, going by the name of Ferris, Twigg and Cash, owned, or had built, or just fitted out, a ship called the Ouzel which was a galley, or a ship named the Ouzel Galley at Ringsend, which was from, or sailed from there. It was dispatched with an unknown quantity of merchandise of one kind or another, in order to trade in the Levant. – A term, which was meant to broadly represent the southern Mediterranean countries, from the middle to the east of.

The ship failed to return, and a claim for its loss was supposedly submitted to the underwriter(S?) or his representative in Dublin, Mr Thompson. The claim was protracted due to the ship being ‘missing’ without any communication, and presumably, the opportunity for fraud which may have arisen. The claim was supposedly in and out of law without success, until it was finally settled by an arbitration committee, which represented both merchants and underwriters.

Surprising all concerned, the Ouzel is then reported to have returned to Dublin with tales of piratical capture and its subsequent adventures on the high seas, until the ship and its crew managed to escape and get back to Dublin. Only, on its return, it carried a much more valuable cargo of booty than the outward one.

The dilemma over who was entitled to what, ended up being presented before the same arbitration committee, and was again settled to everyone’s satisfaction in 1705. The committee distributed the proceeds to distressed merchants and became known thereafter, as the Ouzel Galley Society.

You will have to agree that the story quite conveniently lends itself to embellishment and there has been no shortage of embellishers ever since. But what’s wrong with the story?

For my part, the existence of a ship named ‘Ouzel’ or ‘Ouzel Galley’ and its origins, would seem to represent the classical dichotomy of the ‘chicken & egg’ – which came first? The ship or the story?

We are now going to expand the different elements of the story, as they have previously appeared, and those elements that should be traceable. It may be important to emphasise once more that, thus far, even though the first recorded reference to the Society appeared in the 1740’s, the first reference to such a controversy, or ‘difficulty’ as it was later put, arising in the Port of Dublin, did not appear (Its is said that there is obscure but unsubstantiated reference in the Society’s minutes to a possible earlier existence.) until 1818, more than 100 years later.

The Men

As the ship Ouzel Galley is said by one and all, to have sailed from Ringsend, Dublin, where she was ‘fitted out’ (Some say, built there’) by a single merchant, merchants, or by a Dublin firm of merchants, Ferris, Twigg and Cash, in 1695, let us begin there.

In Dublin’s Calendar of Ancient Records 1698, there is mention of one Thomas Twigg, a Town Clerk. An office holder of some importance, settling disputes over rents and leases, he is also referred to in subsequent years, as captain Thomas Twigg. He died in 1704. The same year, one Thomas Twigg and William Keating are invited to become attorneys for the City.

( John Twigg appears as a member of the Society over a century later.)

There is no mention of Ferris, or Cash in these Records or in Dublin Directories up to this point.

Appearing in the 1731 directory, is one Edward Thompson Esq., with the Revenue Commissioners, and John Twigg, Bridge Street, a Common Councilor.

The Dublin Directory of 1752, lists Joseph Feriss, Fishamble St., and Theophilus Thompson, Merchant of Temple lane. Both appear to have entered the Ouzel Galley Society in 1751.

The firm of Ferris, Twigg and Cash does not appear at all. In a matter of partnership in a ship of adventure for profit, at this time, this was not unusual. The identity of the actual owners of such vessels were often concealed, and sometimes only recorded as ‘Captain & Co.’, as we will discover further on.

According to Kingston in his novel, the outward journey of the Ouzel Galley was under command of Tracey, and the return voyage under Eoghan Massey of Waterford. Lloyds Registers of ships or Lloyd’s List did not exist at the time, so this can not be checked. He does mention the firm and the persons, Ferris Twig & Cash, but there is no mention of such a ship or crew in contemporary news media. Neither is there any matching entry in the Prize Court records nor in the Admiralty High Court records of ‘Letters of Marque’ issued from 1698-1705.

A merchantman of this period need not have carried the permissions of a private ship of war, but given the complexion of the times, trading to the Levant could be a very profitable, but risky business.

Records on file for this period in the National Archives at Kew do contain a very interesting mention of the Oursell Galley, owned by a man of the same name – and we will return to him further on.

The Ship.

The ‘story’ sometimes describes the Ouzel Galley as an armed privateer or merchantman. This description kind of fits its depiction in the painting of the ‘Ouzel Galley’, which was said to have been commissioned by John Maccarel, the Lord Mayor of Dublin. Maccarel was ‘captain’ of the Ouzel Galley Society, when he presented it to the Society in 1753. And while we are at it, this painting, which survives today, is not a depiction of a ship that is a galley – having no visible ports for oars. Nor is it of a classic galley type construction. It is painted with 20 gun ports, and it is at least, twice the tonnage George Little said it could not have been more than, – i.e., 99 tons.

It is worth mentioning here, that news reports, e.g. ‘Ship News‘, drastically abbreviated content while reporting on the movement of vessels. In consequence it was common to see the reports such as; ‘Ouzel-Galley-Murphy-Trinidad’. Which meant that the ship Ouzel, a galley, under command of captain Murphy, had arrived from Trinidad. This type of abbreviation was common and could be misleading.

Interestingly and not uncommon at the time, Kingston’s novel (1877), does describe the Ouzel Galley as having a latine sail on the mizen, as is shown in the painting (1753). The painting is however, a depiction of an armed bluff-bowed merchantman, a typical large privateer, albeit, seemingly a little later than 1695. Furthermore, it is extremely unlikely that the ship depicted in this painting, was capable of being rowed.

Strikingly similar to HMS Charles above), is the purported painting of the Ouzel Galley, presented by John Maccarel to the Society in 1753. The HMS Charles is twice the tonnage and was propelled by 40 oarsmen.

The Ouzel Galley was supposedly loaded with a ‘valuable cargo’ when she set out for the Levant. As an outward consignment, her cargo might typically have comprised of general trading goods, leathers, wool, candles and maybe some iron implements, but if the ‘story’ is suggesting she was a trader only, this might represent a contradiction of purpose.

A privateer, was not an armed merchant vessel per say – there were two types. An armed merchantman that carried a ‘letter of marque’ whilst carrying out its main purpose of trading. Or a privately armed ship for war, with a ‘letter of marque’, allowing it to attack the State’s enemies during war, and was it’s main purpose.

The ‘letter of marque’ from the State or the Crown was awarded to the ship’s owners, captain and crew. The ‘letter’ was awarded after a bond of ‘English money’ and various documents were put on deposit by said owners.

A privateer carried almost three times the normal amount of crew. Three times 40 is 120. These were not just sailors but fierce fighting men out for a ‘piece of the cake’. The large number was required in order to overcome its enemies, after they hoisted the Red Flag and ‘came up’ on an enemy ship. After the ship, usually a trader, had been overcome and surrendered, it and its crew were taken into port, where the value of the ‘prize’ was adjudicated by the Admiralty Prize Courts, and divided amongst the privateer owners, crew and Crown. Many men became very wealthy as a result of their efforts in this regard.

So, although there would have been little room for bulky cargoes aboard a privateer, there were incidents when some captured cargoes were loaded into the privateer, such as in, ‘being very valuable – gold & silver’. It is nevertheless, a little unlikely that, a privateering vessel set out from Dublin with a bulky cargo, in order to just trade in the Levant in 1695.

The Dublin Chamber of Commerce in official correspondence on the origin’s of the Ouzel Galley Society’s have stated that, the ship took its name ‘…from a merchant ship which set sail from Ringsend, Dublin in 1695 and was eventually presumed lost, only to reappear in her home port in 1700 with pirate loot.’only to

The statement is less than categoric. It does not say that the ship was built, was from, or registered at Dublin, and that it returned to its ‘home port’, wherever that actually was.

About eighty years later, bearing the totally dissimilar name, Fame, but owned by some members of the Ouzel Galley Society, did leave Ringsend, on an uncanningly similar and extraordinary adventure. Its story will also appear further on.

Quite surprisingly, in 1845, a ship named the Ouzel Galley, one well documented and also owned by members of the Society was being run out of Dublin to the West Indies. She also left Dublin in 1859, ‘never’ to return! Or did she return somewhere? It’s story will appear in the next ‘log entry’.

The Settlements.

The ‘story’ of our first Ouzel Galley continues with the revelation of her disappearance, i.e. not returning within some pre designated period of time. A period that was not stated. Nothing was heard from the ship, and in 1698 c, it is told that, the owner merchants eventually submitted a claim to the underwriters for the loss of the hull and the cargo therein. Given that there was some opportunity here for fraud, the underwriters were reluctant to pay up – as the canny lot are oft to be.

The case was supposedly in and out of judicial hearings with no result, and as the story sometimes goes, except for the lawyers, both sides were despondent of reaching a settlement. So, an adjudicating committee of impartial insurers and well intentioned merchants was established – 6 from each side. The case was soon settled, giving some credence to the novel, but not an uncommon method of resolving commercial disputes at the time.

No legal record of such a dispute could be located in judicial archives.

Here again, there may be some doubt, especially if we take the word of the giant insurer Aviva, on the history of marine insurance, when it says:

“The first corporate marine insurers in Europe, as distinct from the individual marine underwriters, were the Royal Exchange Assurance and the London Assurance, both established in London in 1720.”

This would appear to rule out a ‘marine insurance’ company, but not an individual(s) underwriter, such as Kingston’s Mr Thompson. It would also appear that, underwriting marine risk, or maybe any risk, is a very old practice, and a ‘relatively mature European insurance market’ existed during the 17th century. ( Violet Barbour, ‘Marine Risk & Insurance in the 17th century.’)

Between 1698 and 1700, a fly in the form of the missing ship, eventually showed up in the Dublin ointment, and the cat was once again amongst the merchant pigeons.

The underwriters had reportedly already paid out on the hull and cargo, and the merchants had accepted the award, relinquishing any further claim over the vessel. So, who then owned the returned ship, the ‘Ouzel Galley’, and her new and supposedly more valuable inward cargo?

Normally, if a settlement is made by an underwriter on the insurance value of a ship’s hull and the owners relinquish any further interest in her, its ownership may revert to the underwriters. If at the time of the supposed return of the vessel, she was owned by the underwriter, one would imagine that they also owned what was in it – but not necessarily. (We are assuming here, that hull and cargo were insured by the same underwriters – otherwise it could very complicated, and we’ll never finish.)

The captain and crew might theoretically have had a strong case for part ownership of a large part of her cargo, which they secured with their own time and expertise, albeit with someone else’s vessel?

An argument being that, the underwriters property, the ship, was used to transport the new cargo and that, the crew’s actions were responsible for acquiring the cargo. The merchant’s case for ownership at this point being much weakened by their earlier acceptance of settlement.

Again, under the auspices of the earlier committee, a settlement was supposedly reached in 1705. Who got what, and what the underwriters did with the ship, was not revealed in any subsequent ‘story’?

No supporting documents of this second adjudication have ever been found.

The Galley’s Antiquities.

Apart from the painting, some other impressive items of the Society remain; bosun’s whistle, medals, crystal glass etc. The ships that are shown on the medals are confusingly different, and were probably not meant to be an accurate image of the legendary ship. The medals and crystal goblet are dated 1850’s, and even the painting, which was out of the Society’s possession until 1870, are of little help in verifying the Society’s earliest date of establishment. The beautiful whistle is dated c.1770. And of course, not to forget the Society’s most valuable asset; its fascinating archives in the Royal Irish Academy.

This ‘story’, a ship named Ouzel or ‘the Ouzel Galley’ and its controversial return to Dublin ended in 1705. The successful arbitration committee was then reportedly institutionalised as the Ouzel Galley Society, Ouzel Galley Arbitration Society, the Ousle Society or the Ouzel or even Ously Galley Club. All these titles and others with obvious misspellings, can be seen in newspaper reports from the 1760’s onwards – but not before.

What valuable cargo was aboard the Ouzel when she returned, what its value was, and what became of the ship and its crew, are details which remained a mystery.

So, is that it then – end of the line? Well no, there’s plenty more, but nothing in the intervening fifty or so years, and later, from Cullen’s research, one of the earliest mentions in the public media of the Ouzel Galley Society in 1761.

Again, contributions are invited from above and below decks.

Log Entry, December, 2013.

The Ouzel Returns but Disappears again.

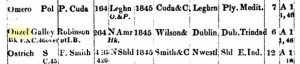

Notwithstanding mariners’ superstition and a most uncommon name given to a ship; in 1845, a 262 ton sailing ship was built in North America, and according to Lloyds Register, was owned and delivered to Wilson & Co of Dublin. It’s registered name was, Ouzel Galley.

The company, Joseph Wilson & Sons Ltd., was established by Joseph Wilson, a Scottish presbyterian, who emigrated to Ireland and then to America, where he served with George Washington in the American Revolution. He returned to Ireland and was appointed American Consul in the port of Dublin in 1794. He established a trading company at 10 Ormond Quay (Wilson also owned and lived at ‘Thorndale’, Drumcondra, and had a large house in Stillorgan.) where he resided much of the time, traded, and carried out his consular duties. Consularship passed through the Wilson family.

The name given to Wilson’s new ship, was not just registered as Ouzel, but ‘Ouzel Galley’. As she was not a galley, but registered as a bark (barque), the naming in this circumstance, is coincidentally specific. The owner(s), we will discover, was more than familiar with the Society, and therefore, would have been equally knowledgeable with the history of its Ouzel Galley and it’s origins – if the ‘story’ is true.

These details could not have been known to the author Kingston, who did not arrive in the hallowed halls, until about the time the owner of the Ouzel Galley, Thomas Wilson, son of Joseph, departed on one’s final voyage. And, shortly before the coincidental loss of the same ship. Kingston’s ‘story’, would not follow until twenty years later.

This second Ouzel Galley ship, did not trade in the Levant. But, just as in Kingston’s novel, traded to the West Indies in the sugar trade. Suggesting source material for Kingston’s ‘Missing Ship’.

It was the new age of steam, and the galley ships had all but been consigned to history. For a wealthy member of the Ouzel Galley Society to have had a ship built, and given that specific name, which included the word ‘galley’, could, in my humble opinion, only have meant that, he was making a point – as ship’s names generally do.

Reported to have been ‘heavily insured’, this second Ouzel Galley was listed, ‘lost’ on March 4, 1859, (out of Registers after 1859) while sailing from Trinidad to Dublin, under the command of captain T. Hulpin(Halpin). The Registers record that, captains Robinson and Fletcher had been in earlier command of the ship, and that after a stint in command of Wilson’s emigrant ship Wave, Halpin took over in her latter years.

While on a return voyage from Trinidad, Halpin and the crew, bar one, were saved by a passing ship, when the Ouzel Galley was ‘wrecked’, more correctly, when it was “abandoned” in a storm off Bermuda, in 1859.

(Captain Thomas Halpin was one of the well known Halpins of Dublin Port and Wicklow. He married at Powerscourt church in Enniskerry, and lived at nearby Monastery House. He is interred at the family vault in Wicklow.)

This Ouzel Galley (the 2nd) was struck by massive waves during a hurricane, and became dismasted and severely damaged, while enroute from Trinidad to Dublin.

Captain Halpin and several of the sailors were injured and Robert Owen, who was from Dublin and at the wheel at the time, was lost. The passing American ship, the Anne E Hooper, took three days to rescue all of the crew, bar one.

Lloyds reported on April 1, that the rescue took place at 33.43N, 54.18W, which is off Bermuda. This is pretty precise reporting, in terms of shipwreck and rescue from that part of the world at that time.

The crew of the Ann E Hooper were later publicly honoured, and received handsome telescopes from the British Government. One of these fine telescopes has been on sale recently in America. It is engraved with the commendation and gifted to the crewman ‘Stocker’. Mistakenly or otherwise, the crewman’s name was reported to have been my own namesake – Stokes.

Telescope presented to crewman of the Ann E Hooper for the rescue of crew from wrecked ship Ouzel Galley

Ship News from Marseilles, dated May 11, reported that a three masted bark was observed at 34S. 51W. Seeing that it was also reported as 34N. 5W., it is only logical to assume that the correct position was 34N. 51W. The ship was reported to have had; ‘lost her mizen mast, and jib boom, sails in ribbons, larboard stanchions and bulwarks, and a great part of her poop carried away. Marked on her stern – Ouzel Galley of Dublin.’

The Ouzel Galley had obviously suffered terrible damage – but clearly she remained afloat after being abandoned, and was later seen to be drifting eastwards. So what became of her?

A distinct feeling of ‘Deja vu’ begins to settle over our second Ouzel Galley legend! What did the underwriters do? The ship was abandoned but was still afloat – did they pay up? Did the Ann E Hooper subsequently make some kind of claim? Did the Galley finally sink? The ship’s registered owners had remained Wilson & Co until this incident, and then it disappeared from the Lloyd’s Registers.

Life on the sea, could be a hard one. The same month another large east-coast American clipper entered the history books, for an even more regrettable reason, when she became one of the worst shipwrecks recorded on the coast of Ireland. Captain Merrihew in command of the Pomona, wrecked on a notorious sandbank, the Blackwater Bank off Wexford. There were 448 on board and 424 were lost, a relatively short distance from the shore.

Ann E Hooper also became a total wreck three years later off Liverpool, losing four of her crew.

Painting by W. Parkes of the rescue by the Ann E. Hooper of the Ouzel Galley from Dublin. Presented to Captain W.Hooper. All rights of reproduction held by Mariners Museum USA.

There is an interesting connection worth mentioning here. The artist who was given the commision to paint the rescue scene for captain Hooper, is believed to have been W.G. Parke. As the artists first name is obscure, the painting could have been completed by his son (but unlikely due to age) or his wife. Parke was a skilled shipbuilder and painter, and moved to Liverpool in 1848. His son, W.H., also a painter, returned to America in 1871. Most of Parke’s work is of a maritime nature, completing some notable works for Irish customers. The painter, Walters, was also in Liverpool at the same time, and completed a painting of the Great Eastern for Robert Halpin, a brother of Thomas, mentioned earlier.

(See suggested correction by Cormac Lowth below.)

More about the Wilsons.

Joseph, of Joseph Wilson and Sons, with ‘partner’, Henry Daniel(s) Brooke (Coolock House*) (Brooke has been described as a ‘partner’ in the company, but was described by Joseph Wilson in his will, as his ‘Assistant in business’, with guaranteed entitlements to a share in the company’s profits. Wilson died in 1809 and Brooke in the Isle of Man in 1847.) was a wealthy ship owner in Dublin, with extensive plantation and sugar-growing interests in Trinidad and America. Thomas Wilson was Joseph’s son, and it would appear that the family company owned this second Ouzel Galley(1845). They also had offices on the North Wall, Dublin. Wilson had a grandson Joseph by a second marriage.

The company, along with other prominent Dublin shippers, was also active in the extensive and lucrative transport of migrants to America right up to the Famine years.

Thomas’s legacy is somewhat coloured by the comments attributed to him during the period of the ‘Famine’, and as an American Consul. Relaying to his masters, intelligence of the commercial opportunities that presented during this historic disaster.

Joseph Wilson was a member and Chairman of the Ouzel Galley Society from 1792, and possibly earlier as per Cullen).

Thomas Wilson was a member of the Ouzel Galley Society in 1812, holding the title of ‘Carpenter’ in 1829, and in 1830 ‘Gunner’, as ‘Boatswain’ in 1834, ‘2nd Lieutenant’ in 1843 and finally, as ‘Ist.Lieutenant’ in 1846. (Little)

Henry Daniel Brooke was a member of the Society in 1824. (Same year he purchased Coolock House.

Wilson was obviously aware of the proclaimed origins of the Ouzel Galley Society and its reported relationship with a ship that had got into ‘difficulty’ in Dublin Port. So, why did he name his ship after his ‘Club’? Or was it that, he named his own ship after the original Ouzel Galley?

Thomas was known as the Croesus of Dublin.(E.McMahon) but died in 1857, two years before the loss of the second Ouzel Galley. (Croesus was king of Lydia (Turkey and conquered the Greeks. He was considered to be fabulously wealthy.)

The Wilson story is one of those true and fascinating epics, and worthy of further study and publication.

*Brooke bought Coolock House from Catherine McCauley of Sisters of Mercy and Mercy House in Baggot Street, in 1828, for £1000 pounds.

The reader will have realised by now, that much hinges on Kingston and his novel – ‘The Missing Ship’. It is now time to examine Kingston’s connection with the Society, and the ‘story’.

W.H.G. Kingston.

William Henry Giles Kingston was born in London in 1814. His father was in the wine business in Portugal and he lived there for a number of years, and even entered into the family trade. Not happy, he pursued a career in writing and produced a prolific number, of what are described as, ‘boys’ adventure stories’. His connection with Dublin and the Ouzel Galley Society, in this respect, is not immediately obvious.

Kingston had a cousin in Dublin, Sir John Kingston James. Sir James, another member of the Ouzel Galley Society. He was also lord mayor of Dublin, and bestowed with a Baronetcy in 1823. He was married to Charlotte Cash, a name we came across earlier, daughter of John Cash, also Lord Mayor of Dublin, and both families were in the wine business, trading between Dublin and the West Indies – as it happens.

The novelist Kingston, visited his cousin in Dublin in 1856/7. This is the year Thomas Wilson, the owner of the Ouzel Galley(2nd) died, and two years before its abandonment in the Atlantic ocean. It was twenty years before the ‘story’ would be first published.

Sir John Kingston James died in 1869, after which Kingston the novelist, was apparently ‘released’ to publish the ‘story’, which apparently first appeared in print, in 1876. The novelist died in 1884.

The story of this second Ouzel Galley, and any possible connection with the ‘story’, will be pursued, and results will appear in the log entry for January, 2014

End of Log Entry. Roy Stokes.

——————————

Log Entry, January, 2014.

Did Kingston use the story of the ‘second’, Wilson’s Ouzel Galley, as source material for the later novel, ‘The Missing Ship’? It seems a logical conclusion, but I don’t know.

There remains one unavoidable fact. The Ouzel Galley Society has been named thus, from as far back as, at least the middle of the 18th century, so they had an indisputable connection with an Ouzel, a galley ship called the Ouzel, or an eating house called the Ouzel Galley. Alternatively, the Ouzel Galley was never a ship but a ‘platform’ on which the Ouzel Galley Society was launched.

As already stated, the earliest documented mention of such a ship and its associated arbitration, was made in Warburton, Whitelaw & Walshe’s History of Dublin in 1818. (This maybe the earliest mention but quite late in terms of its story.) In this, they referred to a ship presenting ‘controversy and legal perplexity’ in Dublin – 1700. It is accepted that, they are referring to the Ouzel Galley, but don’t categorically state its name. By then, the Society has already been in existence for more than half a century and would have been an obvious point of reference for any such research. Therefore, an influence can be assumed to have been possible, as no evidence of any other supporting evidence was presented by them.

What also remains a mystery is – why? Why would anyone create such a story?

The ship Fame and Similarities.

If Kingston collected material for his ‘Missing Ship’ from Society sources, he may well have consulted more than one account of romantic seafaring. And one of the most, if not, the most exciting accounts of an Irish privateer, would hardly have escaped a telling. The ship was the Fame and its owners, prominent merchants, were directly connected with the Ouzel Galley Society in the year of her launch in 1778. The most detailed account of the Fame’s history to date, is ‘The Fame Privateer of Dublin’ by Sean T Rickard.

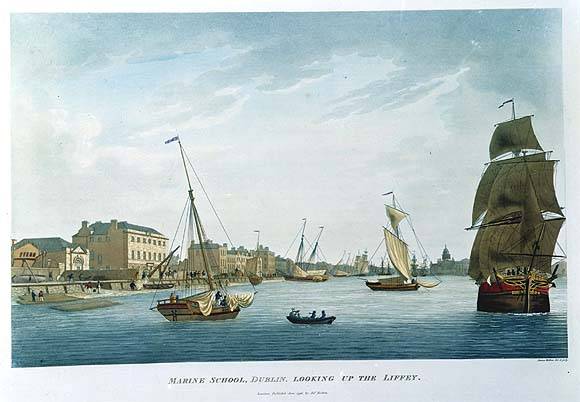

The building of this ship would seem to have represented an important milestone in shipbuilding at Dublin. Or more precisely – at Ringsend. Given that the inhabitants of this spit of land, bounded by the river Dodder on the one side, and Dublin Bay on the other, was separated from the environs of Dublin for centuries, before early bridges at Ballsbridge and Sandymount, and considered themselves a town, apart from the city.

Despite now being considered as part of the general sprawl of Dublin city, the inhabitants of Ringsend remain proud of the notion of being ‘separate’.

The Fame was built by the King brothers at their yard on the Dodder at Thorncastle Street, Ringsend. A little further up the road, at what had previously been, the Sign of the Merrion Arms, was the Marine School for young boys. Established in 1760, it provided an education for boys of poor circumstances, and prepared them for a life at sea. The education, Protestants only, became a sought-after one, as there are recorded incidences of refusal to some applicants, who even volunteered to pay. And as it happens, were constant recipients of donations made by the Ouzel Galley Society.

The Fame was registered as 250 tons, had 20 carriage guns and swivels, and was a galley. She was reported to have been ‘rigged as a schooner’. There were additional ports between each gun-port for oars. Her registered captain at time she was launched, was Edward Moore. After the ship was launched, fitted out, she dropped down to the Yacht Pool at below Rings end and was armed.

Seizing the opportunity from the publicity of the exciting event no doubt, quite a different article appeared, applauding the opportunities in the recent launch of the privateer Fame. This outlined how the Ouzel Galley Society might establish a fund of £20,000 from investors’ subscriptions of, £10 per share, for those who wished become ‘adventurers’ in the business of privateering.

The article appeared on September 26, 1778, and was clearly a kite-flying exercise by the editor, the Ouzel Galley Society (called a Club) or both. It called on investors to dip their toes in the lucrative business of privateering, at a time of the American wars. Large amounts of money were being made, seizing ships under the Prize Rules of war, which adjudicated on vessels shrouded in webs of true nationality, intention and ownership, and just the plain old maritime trade.

The Fame was captained by Edward Moore, and just before he sailed his wife died in Dublin. The Ringsend privateer was joined by a number of other privateers near Ringsend. Captain and crew, paid in advance, sailed with the bristling flotilla for the Levant before just before Christmas.

(Why subsequent correspondence from Europe, both from the Fame’s captain, and others, giving the captain of the Fame’s name as, Thomas Moore, and clearly as Edward Moore on other documents, including the declarations made to obtain the ‘Letter of Marque’, is hard to decipher. It is believed now that Thomas was Edward’s son. There were a number of ‘Moores’’ voyaging to and from the West Indies and Europe at the time, and their name had strong connections with northern Ireland and the Isle of Man.)

The Fame sailed into the Levant and the history books. Capturing a number of valuable prizes and acquitted herself with great panache in a number engagements. The captain and ship won the admiration and accolades from no less than, prominent admirals in the RN.

The Fame was four or five years at sea, and even became ‘lost’ for a while, before she was sold to a Russian agent in Leghorn, after she became ‘tired’. The agent, apparently wanting to transport a booty of ‘curiosities’ collected in Italy, back to his Empress. Reminiscent of the notable losses by La Touche in the Recovery and Cloncurry in the Aid, when they wrecked on the coast of Ireland.

Edward Moore returned to Ireland and arrived in Dublin to assume command of the ‘large armed Revenue cutter’ (‘cruiser’ elsewhere) Annesley, built in Cardiff’s yard at Sir John Rogerson’s Quay (Another Dublin shipyard we know very little about) in 1786. Coincidentally, only months just before the ‘largest ship ever built in Dublin,’ compared to an East Indiaman at 350 tons, was also launched at Cardiff’s yard.

The cutter was stationed at Buncrana to tackle the growing threat presented by the smugglers in that region.

Referring to certain parts of the coast, the Lords were only too aware; ‘That smuggling was never carried on with such spirit and success or on so large a scale as lately…’ They were also aware that their men, equipment and shore facilities were severely overstretched, non existent on some parts of the coast, and that this had severely impacted on morale.

Referring to Cork, ‘They were also informed that there is reason to suspect that a pernicious correspondence is kept up between the smugglers and some officers of that port’.

The Commissioners needed better men and better ships, and Moore’s reputation preceded him. Who better to catch a thief?

Shipyards at Ringsend.

Cardiff’s Yard was situated on the east side of the Hibernian Marine School on the River Liffey. The Marine school for boys had outgrown its earlier converted inn, and moved from Ringsend in 1773. Cardiff would seemed to have been a serious competitor to King, while the Commissioners were having boats built in both yards at the same time.

Kings Yard (‘The Kings Yard’) is shown on ‘Ringsend and Irishtown Landuse and Conditions of Housing’ map 1831 (See image). It was situated on the Liffey side of Ringsend Bridge, between Thorncastle St and the Dodder River – extensive.

Confusion arose between the title, ‘the Kings Yard’ and and ‘Mr Kings Yard’? Was it a Royal Navy, the King’s yard? Or a yard owned by a man named King? The ‘Kings Yard’ quite likely meant that, it belonged to the brothers Eamon and John King, ‘the Kings’. The Revenue Commissioners had a number of vessels built in the yard by the ‘ship’s carpenter, Henry King’, and they referred to the yard as, Kings yard.

Adding to the confusion, the Commissioners also referred to it as, ‘the Crown’s Dock yard’.

The relationship between the Commissioners and Kings yard remains for the time, ambiguous, as they also paid for some works pertaining to the security of this yard. It may be, as in other yards and stores, which were to referred by the authorities, as The King’s Store etc.., that there is a suggestion that some part of the space in these places, was leased for the use of the State. And in the case of the shipyard at Ringsend, it was just a coincidence that the yard’s owner was Mr. King.)

Believed to have been sold on in the East, what became of the Fame and the rest of her crew is unknown. Supposingly, the Ringsenders were repatriated, and maybe not surprisingly, Moore carved out an impressive career in the revenue service.

Fame’s owners were reported to have been Forbes(maybe two) and Dick. They were prominent merchants, and members of the Ouzel Galley Society, as was an Edward Moore. However, the documents relating to the Fame and presented to the Admiralty Court, seeking a ‘Letter of Marque’ and authority to become a private ship of war – had a different name. The application was signed by Isaac and Richard Weld, with Richard’s name crossed out, and stating that, ‘Isaac Weld of Dublin’ was the ‘sole owner’ of the Fame.

Issac and Richard were connected to the well known Separatist preacher, Isaac Weld of Dublin, but were more merchants than preachers, with property in Dublin and London. They also appeared to have become attached to the fruits of ecclesiastical collections at the time, and Issac was declared bankrupt. He nevertheless seems to have ingratiated himself with the Revenue Commissioners in Dublin, and secured an important post in the service.

It is not clear if Isaac Weld was the real owner of the Fame, an investor, or just a front-man for obtaining the licence. The Weld name also appears in membership lists of the Ouzel Galley Society.

Privateering had a well earned and terrible reputation at times, but it nevertheless was a perfectly legal way of making money, and connections with the Society and its members persisted.

There’s no doubt that the story of the Fame has some significant similarities with that of the original Ouzel Galley. It is a cracking story, and it’s true, and should be better documented. I am also convinced, that it was the stuff the likes of which Kingston could easily have used.

So, what are we saying here?

We can say very little, except that the similarities with Ouzel story are striking, but in itself, this is not exceptional.

Revelation that the Ouzel Galley Society’s may have been involved in the promotion of privateering are significant, and hitherto unknown. I n truth it should come as no surpise as many if its members were already heavily involved with slavery. There is no doubt that the Society was not just an arbitration and charitable body, but an organisation whose principal aim, was to improve the positions and fortunes of its merchant members.

Whether or not the Society differs from the Chamber in that respect today, is not apparent.

Further investigations will return to Mr Oursell and his ‘frigot galley’, and will require further research.

End of Log Entry. Roy Stokes.

————————————————

Log entry March 20, 2014.

The Oursel Galley

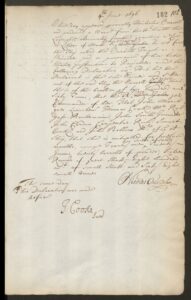

In 2013, a professional researcher in the UK was commissioned to track down any reference or record of a ship by the name of Ouzel Galley. A time window of 1690 -1710 was selected, allowing leeway for the ship being in existence, either before or after the Ouzel Galley’s appearance in the story’s time frame. Records were examined at the Maritime Museum in Greenwich, and at the Public Records Office at Kew. The premise being, that if it could be confirmed that, a ship by the name of Ouzel Galley existed, then this might give weight to origin for the name given to the arbitration committee and the Ouzel Galley Society in Dublin 1705c.

The search for such a name, proved to be as fruitless as the earlier trawl through a considerable volume of media sources and maritime research material. Confirming the superstitiously unpopular use of a name that had any connotations or connection with a ‘black bird’.

As far as such a thing can be determined with any certainty, no mention of such a ship or the event associated with the ship, was discovered.

Just one record, had some interesting similarities.

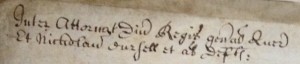

After a double-take on a particular entry, the researcher relayed details of an interesting discovery; a reference to a ship named the Oursel Galley. Also described as the Oursel Frigot, and owned by a man of the same name, Nicolas Oursel.

At this time, 1696, this branch of the Oursel family appears to have lived in London for some time, but probably still had offices or connections in Le Havre and Rouen, where what seems to have been the wider family of Robert Oursell, had been merchants of some significance. Further interest in the Azores and West Indies, were either established later or had already been established by the family before Nicolas Oursel fled to London and was naturalised there. He also had premises and agents in Bristol, the Isle of Man and Dublin.

Daily Courant Aug, 1712.

A parcel of old good neat Fyal Brandy imported by Nicholas Oursell into Bristol and from thence by carriage to London now be sold by John Mathew broker by the pipe £100, the Tun, and by the gallon 9s @ a cellar over against the Dyal in Mariner’s Lane, Cannon Street, none under a gallon…… This brandy little inferior to French Brandy…. End.

Apparently only one of his ships, the Oursel, was similar to that described in the ‘story’. It also bore similarities with the Dublin privateer Fame. She was a privateer of 260 tons (300 elsewhere), 20 guns, and with a crew of 40. Not an uncommon size of basic crew for a ship of that size and type, this was also the same number of crew on which membership of the Society was based. She was however built in New England and captained by Henry Feray.

Some of the crews name’s listed on the Letter were;

Lieutenant-John March, Master-Thomas Cooke, Boatswain-Robert Yate, Gunner-John Sossible(?), Carpenter-John Cardon, Cook -R.i.h.(?) Lissard, Unknown rank-John Bollons.

It should be remembered that the naming of crew of a privateer during the application for a Letter of Mark was often facetious. Ridiculous sounding titles such as, ‘Thomas Beef’ for the cook’s name were entered, suggesting a concealment of the the true names and a ‘thumbing of nose’ at the process.

Nicholas Oursel petitioned the crown in 1696 for permission to register his new ship, the Oursel Galley, (Galley was then stroked over and replaced with ‘frigot’.)with the Admiralty Court as a privateer, and to obtain a Letter of Marque for an initial voyage to Madras, and a return voyage to London. This was not the first privateer in the family.

He was successful in his application, and along with the names of some of the crew, the ship was entered into the Admiralty Court records as such. No further record of the voyage(s) has been discovered to date. The ship was still mentioned in connection with Boston in the early 1700’s.

The Oursells and their Cargoes.

The Oursel family were French Huguenots, and some of these fled persecution in France and settled in London. After taking the Oath, and having received the Sacrament, Nicolas obtained his certificate of naturalisation in 1697. Nicolas was a merchant and ship owner, and was involved in moving goods and people to and from the English Channel, Bristol, the Irish Sea, IOM and Dublin. He and his family were also involved in shipping grain and passengers, mainly Protestants, across the Atlantic. The wider family’s interests extended much further afield.

Nicolas and his wife Elizabeth (A lady by the name of Noemy may have been Nicholas’s first wife.) would seem to have moved to, or settled in Dublin, and became a Freeman of the city in 1711. They had at least two children (several died young), a boy and a girl baptised at Saint Patrick’s.

A significant and repeated feature of Oursell’s operations was his ability to come into conflict with the Crown. There is a considerable amount of material on record at the Public Records Office in Kew, showing just how argumentative Oursel (His representatives seem to have been his wife’s family, Bedford.) had been with the Crown, concerning the price of grain and the legitimacy of the value of the duties imposed on his shipments, cargo and passengers.

His pension seems to have been, to completely overwhelm the Crown’s clerks with extensive written submissions, as to the quality and quantity of the grain, and the costs he incurred while completing the voyages. Negotiating a favourable outcome by the presentation of reasonable and voluminous argument, would seem to have been a favourite strategy of his.

No doubt, such abilities and experience of negotiating with the authorities would have been particularly useful while sitting on any arbitration committee of merchants.

Amory and Oursel.

Thomas Amory was born in Limerick in 1682, was brought to the West Indies while still a child a child, and was returned to London in 1694 for an education. He was hired by Oursell and became a supercargo on his vessels, and a factor for the company in the Azores, before eventually returning to America. His part in Oursell’s business affairs was significant and his acquired knowledge tempted him into shipping on his own account.

As merchants and shippers in Boston, the Amory family maintained connections with Oursel, and became very prominent in the American administration and politics. Thomas Amory died in Boston in 1728.

Other than the word Oursell, as in Oursell Galley, it can otherwise resemble, Ouzel; that is the ‘rs(f)’ appearing to be a ‘Z’, or just an ‘S’

There was little else to attract any further interest, until, I spotted the following account of ships reaching Boston in 1714 and 1717.

Oursell’s surname was spelt in a number of ways, as was his first name. Oursell and Oursel. Nicolas, Nichollas, and Nicholas. His application for a Letter of Marque was signed, ‘Nicolas Oursel’. In older written english a written ‘f’ was an ‘S’ in certain circumstances, and an innocent understanding would assume the ‘R’ in this case, to be an ‘Z’, and one wonders. In such such mis-spellings, as in ‘Moore and the Fame’, was something else being tried on? (See Log Entry, August 8, 2017 below.)

SHIPS FROM IRELAND ARRIVING IN NEW ENGLAND

1714. GRAY-HOUND, sloop, Benjamin Elson, master, from Ireland; arrived April, at Boston (News-Letter, Apr. 19-26,

1714. ELIZABETH & KATHRIN, ship, William Robinson, master, from Ireland; arr. June, at Boston (N. L. May 31-

June 7, 1715. Sick put on shore at Spectacle Island (Province Laws 1714, chapter 45).

MARY ANNE, John Macarell, master, from Ireland; arr. August, at Boston (N. L. Aug. 2-9, 1714)…….

1716 TRUTH AND DAYLIGHT, galley, Robert Campbell, master, from Cork; arr. May 21, at Boston (N. L. May 21-28, 1716; Record Com. Rept. 29, p. 232). Names of passengers given. Outward bound (N. L. May 28-June 4, 1716).

MARY ANN, ship, Robert Maccarell, master, from Dublin; arr. June 18, at Boston (N. L. June 18-25, 1716 ; Record Com. Rept. 29, p. 235). John Gallard and his waiting man.

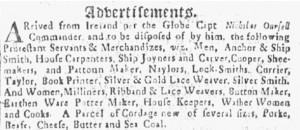

GLOBE, ship, Nicholas Oursell, master, from Ireland; arr. June 25, at Boston (N. L. June 25-June 2, 1716; Record Com. Rept. 29, p. 236). Names of passengers given. Protestants.

The interesting record in these returns was not that of the Globe, from Dublin, and her master, Nicholas Oursel, but another ship that arrived from Dublin within several days of her. The Mary Ann. Very likely to have travelled in company with the Globe from Dublin, it is reasonable to assume then that both men, master/owners, would have known one another quite well – if not at sea, then at the same church in Dublin.

Master of the Mary Ann(Anne) is recorded as having been Robert Macarell(1717), which had been previously commanded by John Macarell(1714). The Macarells in Dublin were also Huguenot. Can we then assume that these two Macarells are related, and that it was this John Macarell, the Dublin wine merchant who became Alderman of Dublin, and none other than one of the oldest recorded members of the Ouzel Galley Society? The same man who later presented the painting of the Ouzel Galley to the Society?

Might we also assume that, Macarell and Oursel, who were both merchants, ship owners, and transporters of a wide variety of human cargoes, and Huguenots to booth, may have been business colleagues – and maybe, what else? As the records of the Ouzel Galley Society for the first half of the 18th century no longer exist, we do do not know if Oursel was a member.

It remains a fact that a number of Dublin‘merchants’ at this time and later, such as Oursel, Weld, Maccarel, Wilson etc’ were involved in a wide variety of shipping, including shipments of HM’s emigrants, HM’s indentured ‘staff’, HM’s prisoners, HM’s troops, and quite probably HM’s slaves. A goodly number of these were also members of the Society.(Distinguishing the ‘Oursells’, a common enough name in France, has proved frustratingly difficult, and quite frankly, beyond me.)

Intriguing as it is, we must desist from further speculative questioning and move on.

A Reluctant Conclusion.

There is no doubt that, there was an arbitration body established in Dublin in the 1740’s called the Ouzel Galley Society, and quite likely, for some unknown period in the preceding years. How, or why it was formed and named at any earlier time, remains unknown.

Given that the history of the Society’s arbitrations mainly involved merchants, ships, and shipping, it should be acceptable to presume that, the earliest body had considerable experience in these matters. It is also true that, its first recorded members quite obviously had, and were indeed, well placed to make successful arbitrations. It is also a fact that, the Society was recognised by the Revenue Commissioners in Ireland as having the competency and legitimacy to arbitrate commercial disagreements, when they referred such matters of dispute to the Society, regarding taxes and levies due by merchants and shippers to the Crown.

And who better than the likes of Nicholas Oursell to have on your side?

(Poor old Nicolas fell foul of one of those perennial ‘bubbles’. In his case, it was the South Sea Company, and not unlike the destruction wrought by today’s financial institutions, good merchants and traders lost heavily to bankers and swindlers, when that company over inflated and burst. He lost heavily and apparently returned to Europe, Rotterdam, and died in 1745.)

It then seems quite likely that, when first naming itself, the committee might have considered a particular incident or ship, or even a person, one that had received some notoriety and suitably well remembered for, before adopting it as their founding title.

It is evident that there is a significant Freemasonry colour to the known membership of the Society. At this time, it appears unlikely that this, or the religious beliefs of the Society’s members, the Protestants of various divisions, Quakers, Huguenots, and Catholics, played any part in arriving at the name chosen for the Society.

The naming of ships continues to prove a great source of entertainment, pride, and benchmarking of historic trends, as do clubs and committees.

We have not solved the mystery, but I do hope we have enlightened and entertained a little along the way. And if we have given fresh material to others, those who may one day solve the riddle of the Ouzel Galley, sure wasn’t it worth it?

End of Log entry. Roy Stokes.

———————————

Log entry, August 13, 2014.

Further research has uncovered this article from the Freeman’s Journal May 23, 1859.

Commercial Intelligence

Dublin Saturday Afternoon.

The barque Ouzel Galley of this port, noticed last week as being overdue with a cargo of sugar, has been reported as abandoned at sea in a sinking state on the 4th of April. The information came by telegraph from New York, and it is supposed that the crew had arrived there. Since the above was received, a French vessel at Marseilles, reports having met the Ouzel Galley at sea, derelict on the 12th of April, eight days after her abandonment. She has not since been heard of. The most probable surmise is that there was a collision with some other vessel, with so much damage as to cause the crew to abandon her.

The Ouzel Galley was built by the late Mr Thomas Wilson, and called after the society of that name, of which he was a member. Some of our readers may not be aware of its origin, and we repeat for their information, that more than 150 years ago, a vessel of this name became the subject of protracted litigation here, and the suit was finally referred to the mercantile arbitration, who had the singular good fortune to please all parties, and were the cause of an association of eminent mercantile gentlemen being formed, and continued to the present time for the purpose of deciding disputed mercantile matters.

The senior member (now Mr Thomas Crostwaite, president of the Chamber of Commerce ) is styled captain, and we believe novices are called upon to discuss(?) and enormous cup of wine on their admission, now, sometimes, it is said, well mixed with water.

The gentlemen just named, Mr Crostwaite, is the only survivor of 392 merchants(892?), who in the close of the last century founded the Commercial Buildings Company

The annual meeting of the Chamber of Commerce will be held on Thursday next, the 26th instant at the Chamber.

We are glad to hear that our remarks as to a test for crushed sugar have been useful.

Printed at the time it was, this statement strongly indicates that such a ship, the Ouzel Galley, existed in Dublin at the close of the 17th century. It also confirms that the second Ouzel Galley was named after the Society, and thus the first Ouzel. As it also came well before Kingston’s novel, it also tends to indicate that the story of the disputed ship Ouzel, might have basis in fact.

End of Log Entry. Roy Stokes.

————————————

Log Entry, August 8, 2017.

A newspaper article covering a highly politicised court case in 1844, reported that the witness, William Cosgrave, secretary (also reported as auditor) to the Ouzel Galley Society (not a member) for twenty years, stated that it was not a society that was incorporated by an Act of Parliament and was 50 years old!

A newspaper article appearing in 1856 stated that the Ouzel Galley Society was established in 1705 and named after a Dutch vessel, whose case gave rise to a great amount of costly litigation. Was this Oursell’s Galley Frigot?

End of Log Entry. Roy Stokes.

————————————

Log Entry, November 19, 2017.

Cormac Louth has very generously made the following suggestion of correction regarding items above, relating to the painting of the Ouzel Galley (2nd).

“Your W.G. and W.H. Parke should read ‘Yorke’ C.”

Despite further research no other ship by the name Ouzel Galley has been discovered. An explanation is still being sought.

End of Log Entry. Roy Stokes

————————————

Log Entry, June 22, 2021.

After some absence and further research and meetings with those that should know, we will review some of the forgoing .

What is the story? There were two stories. The later 19th century Kingston story was novelistic, seemingly designed to fit an 18th century remembrance of the origins of the Ouzel Galley Society. Kingston’s account is a complete mismatch with the older remembrances in so many aspects that it can be easily dismissed as having any relevance to the Society’s beginnings. Seemingly, almost deliberately designed to do so. Amongst many, one clear difference in Kingston’s account, is that the returning ship, Ouzel, a galley, had no booty on board.

Was the second ship, named Ouzel Galley, owned by the Society’s member, John Wilson, just a coincidence of admiration, or was it a demonstration of its owner’s strong belief in the aims of the Society and its ways?

The older story, rumoured that there was gold, gems and treasure on board the returning Ouzel to Dublin from the Levant. The Levant was considered to be that part of the Middle East; Syria, Jordan, Palestine, etc., including Jerusalem. A dispute arose as to who owned the cargo, not the ship. This had been reportedly settled, and the insurers had paid out to the owners for the loss of their ship and its outgoing merchandise. This would normally, not certainly, have left the ownership of the ship and its stores with the insurers.

Where dispute arose, was with the value difference between the loss of the outgoing cargo and the said incoming ‘treasure’ cargo. A difference one might expect to have been great. But, the dispute was reportedly settled, and again, by the group of merchants, who later became the Ouzel Galley Society. However, no mention was ever made of what became of the treasure or the ship.

The turn of the 17th-18th century saw a major schism within Freemasonry. The Ouzel Galley Society has been called a society of Freemasons. No doubt, it has certain symbols and mottos that are not unrelated to Freemasonry, but the suggestion has been denied many times. The fact that membership of the Ouzel Galley Society, forty, modeled on the size of ‘the ship’s’ crew, as set out in the rules of the Society, may be telling.

The various symbols on Dublin Chamber of Commerce, Ouzel Galley, and Commercial Buildings’ headed papers can be interpreted as relating to a Freemasons Society, including the beautiful crystal goblet which was held in trust by the National Museum for the Ouzel Galley Society.

What kind of a ship was it though? Depicted differently in the painting, to the Society’s official headed paper, emblems and plaques, it is hard to say but had a galley design, with oars, in most.

Royal naval ships had set numbers of crew, and a 200 ton brig would have a crew of fifty. The crew of similar size merchant vessels could vary considerably, and a merchant privateer even more so. But why this benevolent and arbitrating Society could or has not varied from a membership of 40, is hard to understand.

Freemasons lodges in Ireland were/are usually reported to be limited to fifty. In the book, ‘Holy Blood and the Holy Grail’, it’s authors point out that the commanderies of the Prieuré de Sion, which they have claimed was associated or was part of an ancient sect of Knights, Masons, Freemasons and almost anything anti Rome, was also confined to forty members. That organisation’s thirteen highest administrative grades, constituting the ‘Rose-Croix’ is also in coincidence with the number of the Ouzel Galley Society’s administrative officers, albeit, they were called its crew, captain, lieutenants, bosun etc.. A principal founder member, Grand Master, Guillaume de Gisors is also reported to have been enrolled in the Order of the Ship.

Described as a dining club,(A popular haunt being the Ship Inn in Chapelizod, Dublin.) an arbitration committee, a do-good Society, the Ouzel Galley Society was not just a group of Sunday worshipping do-gooders. The Galley Society has been comprised of, then and now, some of the most influential and respected politicians and merchants in Ireland. Not to belittle Freemasonry in any way, but often suspected in bad press, of all kinds of nonsense, this Society was and is most certainly not a gathering of nuts. So, why would such a body of esteemed and ‘respectable merchants’ allow such a meandering and sometimes fanciful tales to persist without addressing correction at any time in its history? Can ‘romance’ or pure ignorance of its own history explain?

End of Log Entry. Roy Stokes.

Log Entry, March 15, 2022.

A question arose in 1948 and the same again in 1975. Someone asked; “So how did the sea shanty ballad, The Ouzel, come about”. Was it based on the the mid 19th century merchant ship Ouzel Galley, owned by a member of the Ouzel Galley Society, or was it based on an earlier Ouzel Galley?

The ballad of The Ouzel was collected from Mrs. P. Lett of Ferns, by Jospeh Ranson C.C. It was originally printed in a first edition of, Songs of the Wexford Coast, in 1948, and reprinted by James Hammel Jnr., and John English in 1975. The story and the following tune have been knocking around for quite some time.

The Ouzel

The Ouzel bound for Tropoli, set sail from Dublin town,

And since she was a gallant ship the owners travelled down

To Ringsend in the morning, while the sailors slaved and swore,

To see her slip her old moorings for that rich eastern shore.

She sailed, and from her going came never a message home;

She spoke no deep-sea vessel, and to no port did come.

The galleys from Tunis, by Cadiz in the south

Brought never any tidings of her greybeards or her youth.

“Oh, hide us far among the hills,” the lonely women say;

“We could not see homing ships come across the bay,

Or look upon the sailor lads, who cary victuals down,

As we have carried, long ago, to men we called our own.”

Yet somewhere down by Algiers, on the coast of Barbary,

The Ringsend sailors fought and failed against black piracy,

Their days were dark with agonies, with combatings of pride,

Before the men of Dublin sailed their ship on plunder side.

“For, by Our Lady,” swore the Moors, “this crew’s a gallant band,

And we are less than once we were, swift rapier in each hand.

So sail your ship to orders, and haply you’ll survive;

But flout us or betray us, in chains you’ll take the dive”

So up and down the southern seas, for days and months and year,

A dark and nameless galley played her part in sea mens’ fears.

And down below was treasure great, amassed in many lands,

While Ringsend sailors watched their how to free their shackled hands.

And how they planned and fought, and what their master’s fate

No man of them would ever tell, but whether soon or late,

They won their day of victory upon that southern main,

When desperate and strong-handed they took their ship again.

They set the course for Ireland; they slacked not sail or gear,

Until against the western sky they saw the Golden Spear.

And thus returned the Ouzel, bright offerings in her hold;

Scarred men and battered ship they came; their ballast – pirate’s gold.

End of Log Entry. Roy stokes

——–

Log Entry October 19, 2023

The picture of the advertising sign for the Ouzel Galley Lounge was added today.

This model supposedly represents the Ouzel Galley, courtesy of Dr. G.A. Little, and appears in the publication, Irish Maritime Survey, 1945. Although the model appears more representative of what that ship could have been like, it is not and does not appear to have been in the possession of the Ouzel Galley Society.

It is interesting to note that, Dr. Little wrote his own story of the ‘Ouzel Galley’, first edition in 1940, another in 1953 and neither contained this image.

End of Log entry. Roy Stokes

——

Log entry December 12, 2024.

Following further research and interviews, a number misconceptions can be cleared up.

The story of the Ouzel Galley; that is the Ouzel, a ship that was ‘missing’, and all the attending names, places and ‘facts’, therein, did not enter the public domain until after the novels by Little and Kingston were published after 1940. They differ insofar as; Little ‘s Ouzel sailed to the Levant in 1695, and Kingston’s Ouzel sailed to the West Indies during the middle of the 19th century, and was no doubt prompted by his visits to the Ouzel Galley Society where he would have become aware of the loss by one of its prominent members, John Wilson, who owned and lost the Ouzel Galley while returning from the West Indies. The ship was abandoned while still afloat and seen a number of times by passing ships but never turned up again.

Other than the presentation of a large painting of a ship that is not a galley, and the formation of the Ouzel Galley Society along the lines of a ship’s crew, there is no mention of an Ouzel ship, nor of a ship that sailed to the Levant and returned to Dublin prior to George Little later writings, and W.H. Kingstons novel in the 1870’s.

The Ouzel Galley Lounge in Commercial Buildings, Dame Street, Dublin, was bought and opened by publican and racehorse owner, Hugo Dolan, to replace the Bodega in 1955. He closed it in 1966.

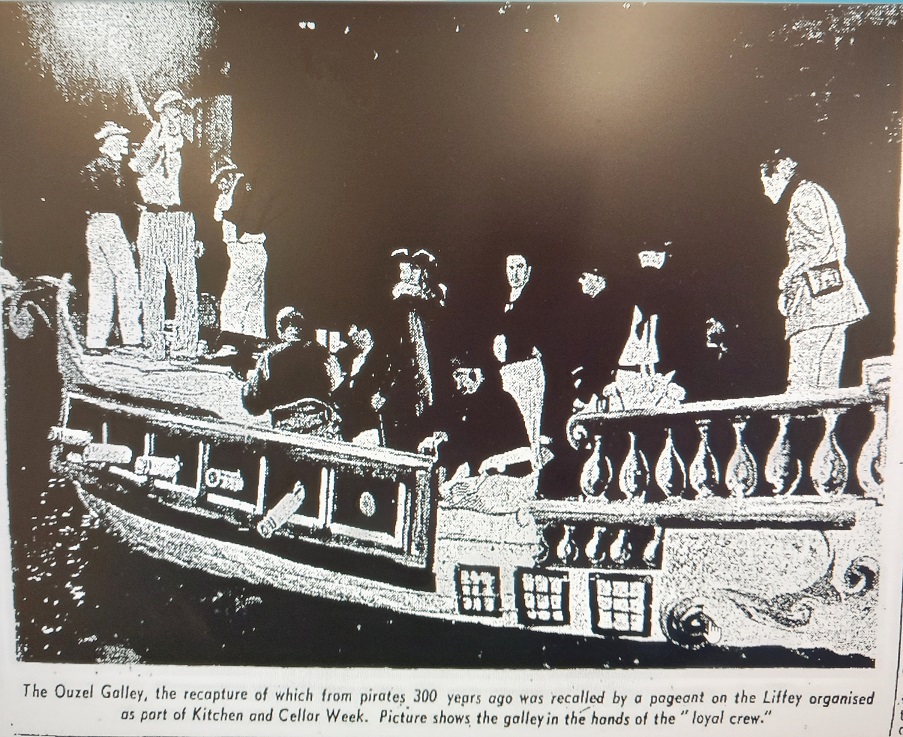

There was a re enactment pageant performed in the River Liffey below O’Connell Bridge, commemorating the exotic legend of the Ouzel Galley in 1959.

Evening Herald 1969

The Ourzel (Frigot) Galley was still trading and privateering when she sailed into Kinsale in 1703. No More is known of her fate. Nicholas Ourzel traded to America and europe with goods and emigrees, alongside a number of Dublin merchants, a group who were were bestowed the title, ‘Freemen of Dublin’.

End of Log entry. Roy Stokes

PLEASE NOTE:- All images, text and video contained in this post, can not be reproduced without permission of the authors or accredited artists..