Even though the young student had little need to describe the lost ship no more than a ‘total wreck’, there’s always a ‘story’.

Commonly addressed by her last Christian name, Stella, Susan was actually the young woman’s first name; her second was Caroline after her mother. 1963, Spring arrived and Stella had only to pop round the corner from where she lived at Merton Drive to her waiting beaux in the Parish Church of Sandford, Ranelagh, south Dublin. Not an unnoticed affair, she was turned out in a dress and train of white French brocade and was wed to Robert Darrell Simpson from Londonderry. Her bridesmaid was her sister Vivien – the best man was Jack Lightbody. After the bouquet was chucked into the cheering party they all hot-footed it out to the old Royal, by then the Grand Hotel in Malahide for the knees up.

Stella and Vivien were of that legendary Arklow maritime name, Tyrrell; daughters of Henry Edward Tyrrell, captain of the coasting motor vessel, Tyrronall. The coaster had been the WW2 prize, Heimat, when she was seized by Britain and renamed, Empire Contamar when Jim Tyrrell bought her as an abandoned wreck in 1947.

Ships’ names have never been bestowed willy-nilly. Obscure to many, ship’s names quite often hold some deep meaning. As with many of the Arklow ships’ their names have comprised of segments from the famous shipping names that have resided in Arklow, those who have been members of the earlier entities of Arklow Shipping; the Tyrrell, Kearon and Hall, giving birth to the evenly comprised, Tyrronall.

By way of another example, some old optimistic wreck diving buddies named their vessels, Alchemist and Deep Concern.

Henry Tyrrell and his family were reported to have moved from Ferrybank in Arklow to the fashionable Roebuck in or around the 1950’s. Their new address was in fact just around the corner, Hollywood Park in Dundrum, where two Tyrell families resided.

The ‘Total Loss’ incident

Thirteen years prior to Stella’s happy occasion, the coasting motor vessel Cameo ran up onto the Arklow Bank, and although she stranded hard on the Bank, she was not abandoned until three days later.

The Cameo had sailed with a cargo of coal from Port Talbot in Wales for Dublin early on Sunday 10th September 1950. She struck and grounded on the middle of the Arklow Bank, almost directly east of Arklow town. A distress call was received at Wicklow, and the lifeboat, Lady Kylsant(Note 1), the RNLI’s first diesel powered lifeboat, ex. Weymouth 1929, and Howth, began the 14 mile journey to the stricken vessel. There were already two Arklow trawlers on the scene but the Cameo’s skipper refused to accept any assistance, confidant that his vessel would be got off. So, the lifeboat returned to base.

The next day, a southerly gale developed and the Lady Kylsant was tasked with returning to the vessel and standing by her, while tugs, one from Dublin and the well know Ranger from Liverpool, attempted to free her from the Bank. Attempts failed but the skipper of the Cameo, whether under orders, remained obstinate and refused to be rescued by the lifeboat, which had no option but to return to Wicklow once again.

The following evening, the 12th, the lifeboat was re called to rescue the captain and his men from the Cameo, which by that time, had begun to break and take in water. The Lady Kylsant, set out in the dark at about 9.30 and battled a strong SW wind to reach the sinking ship. Successful in their mission this time, the Cameo’s crew were returned to Wicklow and lodged in the Bridge Tavern, a hostelry that remains alongside the bridge on the quays, still tempting sailors and tourists.

Through excellent manoeuvring by the coxswain and the brave actions of the crew, they succeeded in rescuing all twelve (BOT), (11 as per RNLI), each of whom had jumped one by one from the ship, each time the lifeboat rose to her gunnels. Velum and medal were awarded to the crew of the lifeboat who also received a little over a fiver each.

(Note 1.) This lifeboat was named after the titled, Lady Kylsant, nee Morris, wife of the politically and commercially controversial shipping magnate, Owen Cosby Philips of White Star fame.

‘MV Cameo – A Total Loss’ – Stella’s Winning Essay

At that time of the incident, Stella was set to attend the renowned boarding school for girls, the Collegiate School at Celbridge. A few short years later she submitted an essay in a competition run for under sixteen by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI), who had invited stories of RNLI rescues on the coast of Ireland. Stella had just graduated from the Collegiate school when it was announced in the Wicklow Newsletter, January 1955, and in the winter’s edition of the ‘Irish Life-Boats – Stories of Irish Lifeboat Gallantries’ that, Stella’s essay had been the winner, and her piece became front page news. The official RNLI account of the tragedy had already appeared in the ‘winter edition’, of its journal in 1950.

Now Stella’s story had either recalled additional aspects of the incident, added some personal experience, or she applied some artistic licence to the story. She wrote that, while staying with a ‘friend’, coxswain of the lifeboat, Inbhear Mór, which was based at Arklow and out of commission at the time of the incident, they had got the call. Arklow was half the Wicklow distance to the tragedy, but their boat, the Inbhear Mór, coxswain, John Hall, being out of commission at the time, was unable to attend!

Stella wrote that she successfully implored her young friend to allow her accompany him on the lifeboat to the scene of the wreck, on this, their third occasion. This being unusual in itself, it was also unusual that she mentioned that he was the coxswain of the Arklow lifeboat. Anyway, she described in some detail the terrible night; ropes fraying, the men jumping off the Cameo, the ship splitting, and the captain – injured, the last man from the Cameo to jump aboard the lifeboat, barely managing to clear the wreck in time.

According to ancient tradition the Cameo had not become a total wreck that night as it was not the case that ‘no living creature had come ashore alive’.

Stella Tyrell’s descriptive essay was deserving of the merit, but has left some of today’s lifeboat men at Arklow scratching their heads.

The Irish Times & Wrecks

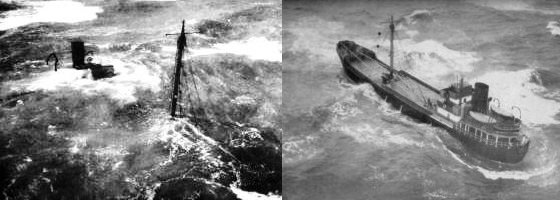

A remarkable feature of the incident, clearly visible in photographs by the Irish Times in 1950, was the speed at which the ship was subsumed into the sandy clutches of the Bank. The Cameo drew only 13 feet 7 inches when she grounded, but settled so quickly that she was never extricated. Undoubtedly cleared later as a navigational hazard, she does not appear to have been commercially salvaged?

The Irish Times, was ahead of the game in aerial photography around Ireland at the time, and photographed a number of shipwrecks, including the Cameo from a light aircraft. Just a few years earlier the same paper produced another set of dramatic photographs of the large motor vessel, Bolivar, which broke in two on the Kish Bank during the memorable winter of 1947. The pilot in that case was W. Cusack and the photographer was the well known Dermot Barry. To get the shot, the aeroplane flew at approximately 40 feet above the sea and between the two halves of the wrecked ship to produce a hard to beat photograph of another loss with a great story.

The Cameo and Her Story

The world had moved on from timber and sail, and the old excuses that were proffered after such tragedies were no longer easily accepted. The Cameo was a modern, oil-fired-engine steel coaster in excellent condition. Almost 1000 tons, 200 feet long – give or take, she was built by Inglis & Co., Scotland, in 1937 and owned by her original but recently re constituted private company, William Robertson Ship Owners Ltd. Founded by William Robertson, the company had been in existence for almost a century. It later became the Gem Line and also ventured into a wide variety of international ‘geological research’. (World renowned Robertson Research Holdings Ltd.).

The Cameo was just 13 years old when she was lost, not an old ship by any standard. She was built of steel on the Clyde by the renowned Inglis & Co., and her machinery was manufactured and fitted by Harland & Wolf. A modern ship with an oil fired engine in the stern, short shaft, and secondary machinery that was largely electric, should not have run aground in fair enough weather in the Irish Sea. Almost as though expecting conflict, she had been initially fitted with heavy lifting machinery, and spacious holds with modern systems of hatch coverings fore and aft of a central derrick.

Regulations, equipment and navigation buoyage, had attained high standards, and by this time, attempts to enter mitigating factors, such as a faulty compass, no longer ‘cut the mustard’. The captain, George Forbes Esson (61), and the the first officer, George Howard Robinson (A familiar name in the sailing ships of Littlehampton.), were found to be ‘seriously at fault’, due to ‘poor navigation’, and their tickets were suspended for six months.

It was common for ships officers to be moved around a company’s fleet and Captain Forbes had only resumed command of the Cameo in July. The court’s finding was recorded on the men’s service record but they could continue sailing in a lower rank and have their tickets restored at the later date.

A public document, the BOT court report, was published in 1951, and could be purchased for ‘threepence – net’ – not quite ‘freedom of information’.

Memories of a Total Wreck

It is often the case that one has only to scratch the surface of a shipwreck report and you will find an interesting story. These are, after all, incidents that are acted out on a violent stage; they often contain drama involving desperate sailors, tragedy, and adventure that was often full of danger. Above all, the life is one in which men have chosen to be part of, their way of life, which seems more isolated than those on land, but more ‘free’. These men and sometimes women have sailed their vessels through pages of history and sometimes survived to make more. Discovering them can lead to remarkable surprises.

The Cameo had only seen two years of service in peace time before being thrown into WW2. She was employed during the early months of 1940, shipping material to Caen in France and ultimately helping to evacuate combatants from it until May. This is also the time when Captain Esson lost his twenty year old son, Stephen, a lightweight boxing champ with the RAF squadron 107, while flying a Blenheim bomber over Holland.

The Cameo continued commercial coastal trading, often in convoy and under aerial protection to and from various UK coastal ports before being drawn back directly into conveying war material and some ‘Special Service’ voyages, almost entirely in UK waters. Towards the end of the war she extended voyages further into German ports before resuming to peacetime coastal trading around the UK.

Possibly because of her youth, the wreck of the Cameo has lain on the Arklow Bank for all these years, seemingly of little interest to divers. Indeed, I cannot remember ever seeing another diving club at Arklow. Members of the Marlin sub aqua club re located the wreck of the Cameo some years ago but had only dived the bow area in pretty poor conditions, coming away without expressing any interest in returning – ‘parking that one’.

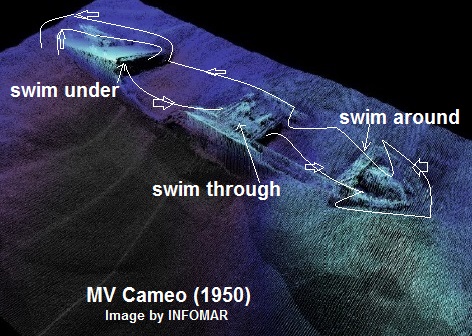

Views changed some years later however, when INFOMAR produced a fascinating 3D image of the wreck. (See image here.)

Diving the Cameo

It was during our ‘heat wave’ in 2022, when the Marlin SA club moved their dive boat from Dun Laoghaire to Arklow. Wrecks were chosen and dives were scheduled, the first being to the Cameo. There was no trouble re locating her remains, but we had forgotten the time of the ‘sweet spot’ – slack water. Or as it has been more colourfully described, ‘The Dead of Neaps’. We camped over the stern of the wreck for two hours, until the tide ceased at ‘LW time Arklow’. (Diving slack at HW – is one hour after.)

First down, we landed beside the capstan on the stern and proceeded around the wreck as shown in the image. It was a very enjoyable long dive, in 5 to 15m’s. Visibility of any quality on the Arklow Bank is hard to achieve but we were kinda lucky. The swim-through under the middle island was quite something, as were all of the nooks and crannies, spotting the various items of equipment and so on. Not known previously for its angling there was a good show of fish life. There is suggestion that the bases of the nearby wind turbines may be improving the habitat for the sea creatures on an otherwise bleak bottom of sand.

Several weeks later the club’s dive boat was returned the not inconsiderable distance by sea to Dublin by the ‘well known diver’ – who also captured the images of the Cameo’s starboard portholes with his GoPro.